Chapter Six

Rochester's Forgotten Regiment:

The 108th New York In The Civil War

By Terence G. Crooks

Chapter Six:

And What Have We Accomplished?

Rain is the great equalizer, the cleanser, wetting Rebel and Federal alike, a reminder that beneath the wet uniform there is human skin, a shared discomfort, a shared humanity. It cleansed the blood from both armies caked on the rails of a ruined fence on the Emmitsburg Road, mixed blood with water in the Wheatfield and washed the ancient stones of the Devil’s Den As an ablution, perhaps, the rain started on the evening of July 3 and continued, with varying intensity, for the next five days.1 Sergeant Woodhull, wounded in the chest during the final charge, lay all night at the field hospital and “it seemed the longest night in my life.” He noticed that every attempt to breathe caused the air to “come through the wound, which made it very difficult to draw my breath.”2 The next morning, he was transported to the Second Corps Hospital, located on the bank of Rock Creek, west of the Jacob Schwartz farm. Once at the hospital, the casualties from Hays’ Division not only suffered from their injuries but faced the unexpected prospect of drowning when the surrounding land became soaked with water as creeks overflowed and hollows became quagmires.3 The sergeant recalled that the heavy rain “flooded us out.” Another flood victim was Jacob Winslow who lay immobile in teeming rain, still paralyzed by his head wound. As he waited for the surgeons, the boy must have wondered why God would subject him to such suffering if He wanted him to be His minister. But Jacob resigned himself, renewed his covenant with the Almighty and knew all would be well. For now and for the war, he was in God’s hands. Other wounded of the 108th stoically wrote that “we are at present lying in a marsh where there is some three inches [of] water under us but it is no person’s fault, it could not be helped.” Some of the injured from the 108th chose not to wait at the hospital. With his arm still numb from the shell fragment, Peter Anger, immediately after the repulse of the Confederate assault, arrived at the division field hospital but “the place was so full of wounded and dying,” so much worse off than he that the sergeant “did not apply for assistance.” He did, however, attempt to find some food around the hospital but was unsuccessful so he “started off to find the regiment.” Near the Baltimore Pike, he fainted “near a large stump and lay there completely exhausted.” Suddenly, a friendly voice inquired, “Hello Sergeant, what is the matter, are you wounded?” Anger recognized the artilleryman as one of Woodruff’s battery and explained his lack of food. The gunner told him to hang on and to “lie still a few minutes.” Shortly afterward, the Good Samaritan “returned with a large cup of coffee and a big chunk of boiled pork” all of which the battered sergeant wolfed down. His left arm continued to throb but at least the gnawing hunger had been assuaged when he finally rejoined the regiment about a mile away.4

Dr. Wafer still worked on the “quarter of an acre” of wounded from both armies that lay on the ground outside the Peter Frey home. He noticed that the enemy wounded

were loudest by far in their outcries for help. I have found this to be invariably the case on subsequent occasions. This I am not prepared to explain. Unless it be that they had no confidence in our humanity and dreaded wilful (sic) neglect.

The doctor quickly dismissed such a thought since he never observed any distinction in the treatment of friend or foe. Despite their efforts, the surgeons were gradually overwhelmed by “the large and helpless mass” of sufferers. When they ran out of bandages, homespun linen sheets from the Frey house were torn into strips which provided a “good substitute while they lasted.” Soon the only water supply, the well, was exhausted and the pain killing liquid morphine, usually diluted with water to dull a searing pain, had to be rationed judiciously. The work never stopped. To add to the madness, Confederate sharpshooters continued the fight by deliberately firing at the Union stretcher-bearers who attempted to move seriously wounded Rebels. Wafer could not fathom “the recklessness or barbarity of their comrades” whose actions condemned the Confederate wounded “to lie another day” without medical aid. To add consciously and without purpose to the already suffering mass of wounded made no sense at all to the doctor from Canada.5

While the doctor maintained his vigil over the physically wounded, the remnants of the 108th New York were emotionally drained and worn out. On the drizzly foggy morning of July 5th, 1863, the regiment moved with its Corps south on the Baltimore Pike to Two Taverns, some five miles away, where they went into bivouac and awaited the arrival of badly needed supplies. Most of the men in the regiment, as well as the brigade, had been without rations since their arrival in Gettysburg the previous Thursday. Miserably, July 6 passed, while stomachs growled in the dreary rain and they became obsessed “with the oft repeated question of something to eat.” On Tuesday, July 7, still without rations, the Second Corps lurched towards Taneytown with the vain hope that their wagon trains would find them. At Taneytown, men were detailed to go into town “and obtain food, the expense of which was to be paid by the government.” One enterprising “patriotic and humane resident of the town sold water from his pump at six cents a glass” which must have endeared him to the battle weary troops of the Second Corps. Later that day when the trains arrived with hard tack and salt pork, the men ate their first meal in five days.6

During the fight at Gettysburg, Lt. Sam Porter suffered severely from the common affliction of chronic diarrhea. Lack of proper food and fresh clean water combined with the sheer terror of combat did little to alleviate his condition. He was trapped in the seemingly endless of cycle of poor diet leading to frequent bowel movements which left him weakened and dehydrated which only further exacerbated the digestive disorder. To his father on July 4, 1863, he wrote reassuringly that his company F “suffered fearfully” in the fight, losing “19 of 32” but he “did not receive a scratch.” However by July 7th, his digestive problem had become acute and constantly threatened embarrassing incontinence. As the 108th retraced its path to Taneytown, Porter’s agony intensified during the exhausting ordeal over roads turned to a muddy soup from the incessant rain. When they arrived at Taneytown, the site selected for the camp of the Third Division, Second Corps proved to be somewhat restrictive so that the brigades in Hays” Division were “crowded severely together” and by the time the distraught young lieutenant showed up the sanitary “sinks had not been dug.” Unfortunately, Porter had the urgent need “to ease himself. He went, as he supposed to a secluded spot across the road and far to the rear of the Barn, no tents or anything apparently to be nuisanced” and ,once there, began to loosen his clothing. At this point, Lt. Frank Aretas Haskell of the 6th Wisconsin and Aide De Camp to Brig. Gen. John Gibbon spotted the luck less Porter in his quest for relief and privacy.7

Haskell, who would later become famous for his epic letter to his brother about the battle of Gettysburg in which he generously assigned himself a starring role, was returning to work at Second Division Headquarters, now under the command of Brigadier Gen. William Harrow. Harrow had taken over after Gibbon was wounded on July 3. When Pickett’s Charge was repulsed, Haskell rushed to find his beloved wounded general and, in a manner reminiscent of Dan Sickles’ haste to report to Lincoln, he was forced to recount the denouement of the battle, including, of course, his significant role. As Gibbon listened to the oration, he undoubtedly expressed to Haskell “that to him more than to any man” the Union army was “indebted for the repulse of Lee’s assault.” So with Gibbon’s praise still ringing his ears as well as his not inconsiderable opinion of himself, Haskell left his general to return to the camp of the Second Corps and spotted a Union soldier going or attempting to go to the toilet within his sight. Such an outrage must have deeply troubled the fastidious aide who gamely suffered from his own Gettysburg wound, a bruise from a spent bullet.8

Wasting no time, Haskell “came rushing across the field with cocked pistol in hand and demanded that he [Porter] should ‘double-quick’ off the field at once.” Porter, probably embarrassed, began “to comply” but, before he could re-assemble his clothing, Haskell again demanded that “he should go ‘double-quick’” and added “go God Damn you or I will shoot you.” Sam Porter, who would turn 20 in just over a month and already a legitimately wounded combat veteran and field officer, must have been singularly unimpressed by this 34 year old martinet staff officer. At the time, Porter was, like Haskell, a first lieutenant, even though he had functioned as the captain of Co. F since the death of Capt. Byron Thrasher at Chancellorsville , two months earlier. Technically, both men were of equal rank, but Sam wore no straps and striped pants to indicate his position, a serious fashion faux-pas that Haskell would never commit.9 Haskell could perhaps sense the contempt so he dismounted as Porter started to move slowly away, rushed up behind the lieutenant and “kicked him severely”. At this point, Porter, having had enough, turned and began to tell Haskell that “he would not take that abuse” and that he would leave the field “like a gentleman.” Before he could get the words out, Haskell fired his pistol and shot Porter in the right shoulder “wounding him severely.” The young man staggered backward as the hole in his uniform smouldered from the close range shot. He made it to the camp of the 108th and went to the tent of Lt.Col. Pierce to report the assault. Pierce was furious and “started for headquarters to investigate the matter” but “was recalled by Col. Powers who said he would attend to it.” Apparently, by this time, Haskell had ridden off. Powers sent in the report and it went as far as temporary Second Corps Commander William Hays who received it on July 8, 1863 and called for a Court of Inquiry “to examine into the Circumstances of the shooting of Lieut. Porter, 108 New York Vols. by Lieut. Haskell ADC”. However “the proceedings of said Court of Inquiry” were never sent to the War Department, probably because the inquiry never occurred. Ironically, Haskell was promoted to William Hays’ aide at Second Corps Head Quarters where some of the other staff officers felt that his shooting of “an officer of some regiment who was committing a nuisance” actually “was the cause of bringing him to our staff”. Also, the fact that Haskell became General Hays’ bartender may have helped in the cover up. Haskell would die 11 months later at Cold Harbor. Porter meanwhile was sent home for well over six weeks and did not rejoin the regiment until late August. According to records, he was wounded at the battle of Gettysburg.10

On July 8, the Second Corps joined the rest of the army to take part in Meade’s pursuit of the Army of Northern Virginia.11 For the 108th New York, their June march to Gettysburg, some 250 strong, was now retraced by less than half that number, a regiment barely the size of a full company. Once more the men from Rochester marched through Frederick with their tattered flags unfurled and their music blaring to the great delight of the friendly populace, who bestowed pies, cakes, milk and buckets of cold water to the tired, thirsty soldiers.12 Eventually, the Army of the Potomac caught up to Lee and his men at Williamsport, where Lee dared Meade to attack. “Everyone now expected a battle at any moment” but “an advance was not made.” The wily Rebel general had been “brought to bay” with a swollen river at his back and “the pontoon train on which he invaded Maryland had been destroyed.” Consequently, “the destruction of his army was regarded as almost certain by most of our officers.” However, it was that “almost” that gave pause as it evoked the familiar spectre of defeat and caused Meade to waver and lose the name of action. Instead of certain destruction for Lee’s army, the tune changed to caution. Lee would defend his position with “desperation.” His line was a crescent, anchored well on both flanks. To attack would mean “tremendous sacrifice of life.”13 By the morning of July 14, it made no difference since Lee and his army were gone, safely back in Virginia and, perhaps, George Meade was glad to see him go. Leaving nothing to supposition, Charles Hale Morgan, Hancock’s Chief of Staff, openly declared “that the Second Corps Headquarters were greatly relieved to find the enemy gone.” For the Second Corps the Gettysburg campaign was concluded but the pursuit of Lee was far from over.14

On the morning of July 15, the 108th New York crossed the battlefield of Antietam. What memories or images the crossing provoked for the boys from Rochester were not recorded but, less than one year before, this was where they were initiated into a select brotherhood of combat veterans. The Corps followed Antietam Creek southward for a while, then crossed near the mouth and followed the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal south to Harper’s Ferry. Amid some afternoon showers, the 108th New York and the rest of the Second Corps bivouacked opposite the Ferry, near Maryland Heights. The next day the Corps moved a few miles further south to the vicinity of Sandy Hook and for the remainder of the 16th and 17th of July, Hays’ Division encamped at the southern base of Maryland Heights where the men received fresh clothing and full rations but no mail from home.15 During their brief sojourn various members from Hays’ Division liberally helped themselves to the straw from a neighboring farmer who, in turn, became furious with their libertine incursions. However the farmer made the mistake of confronting and protesting vigorously to General Alexander Hays. Hays, whose behavior and command style sometimesbordered on the irreverently psychotic, was not going to be hectored by a Maryland farmer! As the farmer remonstrated, Hays leapt to his feet and “went to the door of his tent and looking up and down the camp of the division said ‘Straw, I see no straw. I think you are mistaken.’” At this juncture the farmer’s anger erupted with a burst of swearing. Hays, no stranger himself to the descriptive expletive, was morally outraged by the farmer’s crudeness and suggested some Bible study. In fact, the general took “a Bible from his table” and “presented it to the surprised and disgusted farmer” but, as soldier of the 14th Connecticut wryly remarked the “only drawback to the story is the very remote probability of a Bible being on General Hays table.” 16

For the time being, the Second Corps was stranded until engineers could construct a pontoon bridge slightly north of the railroad bridge. Earlier in the month, the bridges over the Potomac at Harper’s Ferry were destroyed by Federal troops since the enemy had floored the railroad bridge and was crossing the river in small detachments. The “trestle work on each side of the bridge was destroyed as was the bridge over the canal”, but the engineers worked quickly and in the early morning of July 18, the 108th New York crossed the new pontoon bridge.17 While passing through Harper’s Ferry, Francis Wafer, who was not with the regiment when it last camped there, marveled at the scenic location. The topography and geology of the land around the ruined government arsenal fascinated him but sadly he also realized how beautiful the pre-war town must have been. Redolent of “every odour but a pleasant one,” the town stunk and consisted of “crumbling walls and an immense stack of burned gun barrels bent into every conceivable shape.” They moved through the town, crossed the Shenandoah River on a suspension bridge and marched up Loudon Valley, east of the Blue Ridge Mountains.18 To the west, on the other side of the mountains, General Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia were on a parallel course in the Shenandoah Valley. There seemed to be no urgency to the march of the Second Corps – a march up the valley by short stages, numerous rest halts and early bivouacs. To the men in the Second Brigade of Hay’s Division the salient memory of the trek was the massive blackberry hunt at Hillsborough. First Sergeant Andrew Boyd of the 108th New York noted in his diary: “Went out after blackberries; picked about four quarts in half an hour; never saw berries so thick.” Captain Sam Fiske of the 14th Connecticut preferred to see the episode in Biblical terms. The hungry hot soldiers of the corps were “Israelites” wandering “in the wilderness” and the berries were “manna”, a gift from heaven. All in all it was “blackberrying on the grandest scale I have attended for a long time.” In the 12th New Jersey, Azariah Stratton remembered that in the days following he “had berries for supper and berries for breakfast.”19 Drowsy from berries and the late July heat, the Corps languidly passed through Bloomfield, Upperville and on the 23rd approached Manassas Gap where they spent two days supporting the Third Corps’ attempt to damage Lee’s army.

As the Army of Northern Virginia moved up the Shenandoah Valley, the three corps became separated. The Second Corps fell behind the other two when Ewell failed in an attempt to bag a force of Federal troops from the Department of West Virginia, under the command of the patriotically named Brig. Gen. Benjamin Franklin Kelley, who were also engaged in the pursuit of Lee.20 Elements of the Third Corps of the Army of the Potomac, now commanded by Maj. Gen. William (Old Blinky) French who had returned earlier in the month, entered Manassas Gap “at early daylight on the 23rd”, just in time to catch Ewell’s Second Corps isolated from the body of Lee’s army.21Here was an opportunity for French to catch one third of the Army of Northern Virginia and to hold it in place until the bulk of Meade’s army could arrive to destroy it. The only thing stopping French was the brigade of Rans Wright, left behind by Hill to protect Manassas Gap. On July 23, Ambrose Ransom Wright’s Georgia Brigade had a battle strength of maybe 700 men to which Ewell added 250 sharpshooters, under Maj. Eugene Blackford from Rodes’ division, for a front line total of approximately 950 men. French’s Third Corps though horribly mauled at Gettysburg still had two divisions of about 3000 men each for a corps total strength of almost 6500 soldiers – a total which did not include the addition of Brig. Gen. William Hopkins Morris’ Brigade and the “troops which had been left at Harper’s Ferry” under the command of another patriotically named general, Washington Lafayette Elliot. These additions must have bolstered French’s strength to at least 13,000 men.22 If he desired to, French could have put his full weight into the attack since Meade’s other corps were closing in but he chose not to. Instead he sent in Ward’s Division, spear-headed by the Excelsior Brigade commanded by Brig. Gen. Francis Barreto Spinola, a man with little combat experience who managed to get shot twice during the battle of Wapping Heights, as the attack was later named. Wright’s Brigade and Blackford’s sharpshooters held French’s force at bay but towards dusk the Rebels were eventually driven back. On the morning of the 24th , Ewell and his men were gone and so was the opportunity to seriously damage Lee.23

On the 25th of July, the 108th New York and the rest of the Second Corps, who were not heavily involved during their two day stay at Manassas Gap, continued their march “passing out of Manassas Gap in the direction of Warrenton” and paralleling Lee’s left flank.24 Even though the roads were difficult and badly cut up, the Second Corps out marched their wagon train so the men were exhausted and “the stress of hunger was almost unendurable.” They were issued some scanty rations just before they took the march again, but these were hardly sufficient. At the first opportunity, men from Hays’ Division went out on their own shopping spree and liberally “foraged” the area. Alex Hays, who got wind of the unauthorized sortie, “sallied out after them” with the Provost guard and arrested as many as possible. At one point, Hays captured a number of his men in a farmhouse but some managed to hide “in the tall grass in the yard.” Furious and frustrated Hays disregarded his earlier sermon to the Maryland farmer, as he “stood in the path and cursed to them in his unique style saying that he saw them, every one of them, and bidding them to come out and surrender.” Strangely enough, some actually fell for the general’s bluff while others brassed it out “and were not discovered.” Needless to add, when the division entered another blackberry field near Warrenton Junction, discipline once more disintegrated as the “troops broke ranks and individuals began picking blackberries of which there was a great abundance. Hays was completely disgusted by their behaviour and “after considerable exertion got them together long enough to stack arms.” Their march to Warrenton Junction completed a six week cycle that had begun at Falmouth in early June and during which time the 108th New York and its corps had marched 436 miles.25

During the next three days spent at Warrenton Junction, Officers William H. Andrews, J. George Cramer and Dwight Ostrander departed the regiment to be sent home for duty at the recruiting rendezvous of Elmira, New York. Lt. Col. F.E. Pierce, still in command of the regiment, wished that he too could go home but with “Col. Powers and Maj. Hogoboom both being absent sick it was no use” to even submit a request. Pierce hoped that his turn would “come about Christmas.” Major Harmon Hogoboom who suffered from chronic diarrhea and extreme general debility for most of his service with the regiment, never returned to the 108th New York and resigned from the army on a medical certificate, effective July 24th. After his discharge on August 8, 1863, no one replaced Hogoboom so the regiment went through the remainder of the war without an official major.26 On July 30th, the corps moved to Elkton, located on Elk Run and remained in this area until the middle of September. The Second Brigade, which included the 108th New York, was detached on August 1st from the rest of the division and sent about three miles east of Elkton to a spot called Bristerburg which mainly consisted of a store, some houses and a stone church, creatively named Bristerburg Church, which served as the brigade hospital.27

Shortly before the departure to Bristerburg, Dr. Munson left on sick leave, soon followed by Dr. Ely who applied for a staff position at Washington and was ordered there for an examination. Thus the regiment was reduced to one surgeon, Dr. Wafer, to look after the many that “fell sick of fever and bowel disease” exacerbated, no doubt, by lack of regular diet and aggravated by overdoses of blackberries. To compound his problem, the doctor was so ill with pleurisy and general exhaustion that he was forced “to prescribe for my sick men” while “lying on my bed.” Even before Dr. Ely returned on August 17 to relieve him “from further care or duty”, the health of the assistant surgeon continued to decline so much that Wafer applied for medical leave on the 13th of August. On September 2nd, Dr. Ely supported his colleague’s request by certifying that the Canadian surgeon was “suffering from extensive pleurisy of the right side of the chest with marked effusions” and recommended hospitalization. The approval for Wafer’s twenty day leave arrived on September 7 and he reported to Georgetown Officer’s Hospital on September 8.28

For the enlisted men, duty at Bristerburg was not onerous and, during the dog days of August, their health improved significantly. In a letter to his uncle, Morris Darrohn, Company C, explained:

The duty is not very arduous, although we have to go on picket every other day. The picket duty is not verry (sic) hard here for the reason we don’t have to go far from camp. As for rations, we got a plenty. Soft bread 4 days out of 7, the other 3 we get what they call ‘Hardtack.’ Fresh beef and pork all we want.

As a further incentive to well-being, the men received two months back pay on August 5 and were promised more back pay later in the month.29 But August also brought change within the corps. Near the end of the first half of the month, the Second Corps commander, Brigadier General William Hays was replaced by recently appointed Major General Gouvenour Kemble Warren. Hays, who was captured at Chancellorsvile and returned to the army during the Gettysburg Campaign, acquired command of the Second Corps on July 3, 1863, after the wounding of Major General Winfield S. Hancock. Hays would once more return to the Second Corps in the Appomattox Campaign of 1865 but would suffer a rather humiliating removal from command when A.A. Humphreys discovered everyone sound asleep at Hays’ headquarters on the morning of April 6, 1865 during the final crucial pursuit of Lee.30

Warren, usually referred to as ‘The Savior of Little Round Top’, was promoted to Major General of Volunteers on August 8, 1863 “in recognition of his eminent services at Gettysburg” where he served as Chief of Engineers on Meade’s Headquarters Staff. Even though Warren had saved “the glorious field” of Gettysburg, one of his staff recalled, “it altered not his bearing -which was that of the thoughtful, modest scholar rather than the soldier – nor did it kindle any vanity in look or speech.”31 Contemporaries described him as a small man, with straight longish black hair, combed flat over his forehead and small black piercing eyes, one larger than the other, which gave a suggested cast to his look, perhaps the look of an Indian. His appearance often appeared skewed or eccentric since he buttoned his uniform incorrectly, wore pants too short and sported a straw hat to complete his ensemble. In other words, the contrast between Warren and the imperial Hancock was, to put it mildly, remarkable. Even as a teacher of mathematics at West Point, his students noted his grave “almost sympathy-craving” expression on his “dusky sallow face.”32Nevertheless, the absent-minded professor image belied his military ability. He was an excellent engineer who had a keen eye for topography as he demonstrated at the battle of Gettysburg but, like Hamlet, his restless nervous mind saw too many sides of any issue which he felt compelled to bring to the attention of his superiors. His future boss, General Grant wrote:

He could see every danger at a glance before he had encountered it. He would not only make preparations to meet the danger which might occur, but he would inform his commanding officers what others should do while he was executing his move.

Although not untypical for an officer and admirer of George B. McClellan, Warren’s “maddening propensity to forward to headquarters unsolicited opinions and advice concerning both tactical and strategic matters that lay outside of his own immediate area of operations and knowledge” would eventually lead the corps commander to grief and humiliation.33 The meddlesome general had a particular fondness for limericks and spent evenings in his tent crouched over a small volume of limericks, possibly Edward Lear’s Book of Nonsense, first published in 1846. “He would repeat them at almost every meal” and remained oblivious to the fact “that they did not seem nearly so amusing to others as they did to him.” His staffers probably laughed or smiled or rolled their eyes and, perhaps, did not understand that the more complex the mind, the greater the need for simplicity. A Limerick is defined as “a form of light verse, a particularly popular type of nonsense verse.” Its jingoesque rhyme and lilting rhythm combine to trivialize a topic and reduce a complex issue to a simple or irrelevant answer. As a diversion, the limerick would be ideal for a morose intellectual such as Warren in the same way that nonsense verse also provided release for another strange teacher of mathematics, born two years after Warren in 1832, and named Reverend Charles L. Dodgson but better known as Lewis Carroll.34

Although the new corps commander may have been an odd duck when compared to his predecessor, the men from Rochester did not seem to notice. One of Warren’s first orders was for the Second Brigade to be drawn back from Bristerburg on August 17. For the officers of the 108th New York, the return to the Elk Run camp provided an almost pleasant distraction. Sam Porter, recently returned after his shoulder wound, claimed in a lighthearted letter to his father that he has “seen considerable of Virginia” and, in mock heroic prose, wished to be able to “impart the results of my investigation in a manner which will be at least readable.” Whether a result of his experience with Haskell or simply the tedium of the war, Sam’s attitude had hardened and a certain coldness grew within him. As he moved about the Virginia countryside, “the miserable and degraded condition of the people” only confirmed for the young Rochester aristocrat his view of a morally decadent South. To Porter, southern whites “ are on small farms and present the appearance of miserable white trash” whereas the “sole representatives of the grand plantations are in general a negro woman with a large number of children, most of whom bear unmistakable indication of a large admixture of white blood.” Earlier in the letter, he related an episode that occurred during one of his ‘scouts’. Lt. Porter “was sent with a party to scour the country for deserters, suspicious looking individuals, etc.” Also, as part of his interpretation of responsibility, he decided to round up any and all horses bearing “any marks of Uncle Sam’s ownership upon them.” The ‘scout’ seemed to be a euphemism for a foraging expedition since at one point he allowed his men to enter a private dwelling to acquire breakfast. Porter remained outside and, after some snooping, “soon found two horses branded U.S.” which he quickly ordered unhitched. As they were about to leave, an old woman rushed out of the house “threatening dire vengeance on any one who dared touch her horses.” Porter was unmoved by her protestations. The woman attempted “the other tack and tried an appeal to my feelings” but nothing worked on these so-called “ruffianly Yankees” and the horses were reclaimed. Perhaps the most noticeable feature of the entire letter is Porter’s detached, almost clinical, observations. The incident with the old woman was “quite an amusing time.” There is no emotional response. Why mention the mulatto children? Was he sickened by these people? White overseers or masters sexually involved with their ‘chattel’? There is almost a supercilious tone in the descriptive passages – as if he were examining a specimen of bacteria, or a fungus. For Sam, there was no more romance in the war.35

In the last week of August, the regiment was in the Falmouth-Stafford Courthouse area. During one of their far-ranging scouts, the 108th New York recovered one its lost members, Willard H. Peck of Company A. As the regiment marched through Stafford Courthouse on its way to Gettysburg, over a month previous, Willard and his brother William were taken by so-called Confederate guerillas and apparently executed. William died quickly from the gun shot to the back of his head but Willard was more fortunate. Twenty four hours he laid unconscious, his dead brother beside him, but when he awoke and got to his feet and moved in the direction of where he last remembered the regiment to be, he became disoriented and lost in the nearby woods. Two young women found him wandering aimlessly and took him home to their father. When the young ladies arrived home with Peck, their father cut through the blood-clotted mass of hair with shears until the wound was exposed, at which time he pried out a ball and four buckshot pellets. Willard‘s thick hair or maybe his thick head saved his life. He stayed with the family for several weeks but when he learned that the 108th was in the vicinity, he manfully reported back for duty. Willard was sent home, fully expecting to resume active service, but Dr. Backus, post surgeon at Rochester declared him unfit “on account of his wound” and he was out of the war. The body of his brother was never found.36

Early in September, in response to Lee weakening his army with the detachment of two divisions from Longstreet’s Corps to the west, the Union Second Corps crossed the Rappahannock, moved through Culpeper, and then cautiously moved southward to probe the area on the north bank of the Rapidan, opposite Lee’s position at Orange Court House. On the 14th of September, the 108th New York was detached from the Second Brigade of Hays’ Division and was ordered to remain at Pony Mountain, three miles south of Culpeper, while the rest of the Corps moved closer to the Rapidan. Their assignment was to guard the members of the Signal Corps who occupied the position and took observations from an impressive 60 foot platform erected in the trees. Two days later, Warren’s Corps was ordered to picket the area from Cedar Run Mountain to Somerville to Morton’s Ford on the Rapidan. At dusk on the 16th, the regiment was summoned to rejoin the division which was positioned southwest of Somerville Ford near Cedar Run Mountain. Unfortunately, when the regiment moved out in the darkness, the men took the wrong road and were forced to countermarch thereby arriving late on Sept.17.37 They arrived in time, however, for an execution.

While the Army of the Potomac lingered between the Rapidan and the Rappahannock during the autumnal days of September, drastic measures were required to remedy an “infection” that “extended to entire brigades”, namely desertion, cowardice or general dereliction of duty. On September 18, 1863, the ‘cure’ was demonstrated to the Second Corps. For the Union army, Gettysburg marked a turning point in the war but the battle also roughly marked a turning point in the type of soldier who would serve until the finish of the war. The boys in blue of 61’ and 62’ were decimated –the 108th New York left Rochester 1000 strong but after Gettysburg could barely muster 100 men –so the good men were more and more replaced by the “ ‘bounty jumper’ or professional deserter.” Protest riots against the draft in New York City only widened the gulf of difference between the enlisted volunteer and the conscript or substitute of 1863 who was usually poor and lower class. Therefore, for “the needs of the service”, two men from the 14th Connecticut were executed on September 18,1863, in front of their regiment and division. The condemned men, Edward Elliot of Company I and George Laton of Company K, were both from New Haven, the latter a substitute and the former a draftee. In the month of August, 1863, there were 12 other conscripts from New Haven who deserted the regiment. Whether these men knew each other or not cannot be established but the general pattern seemed to be to enlist and then, about 2-3 weeks later, desert the regiment. All fourteen desertions of New Haven conscripts occurred in the latter half of August but only Laton and Elliot were caught, possibly in early September. Rumor had it that as soon as they got “a liberal advance” of their bounty, they “disappeared but were caught somewhere in New York or Boston and brought out to the field to suffer the extreme penalty for their crime.” Court-martialed and sentenced to death, the results of their trials were published about a week before the execution but both men were unaware of their sentence. No one told them until 12p.m. on Friday, Sept. 18, a few hours before their scheduled execution. How the men reacted can only be imagined.38

The ritual began shortly before 1pm. Regiments of the Third Division were required “to fall in and march up to the place of execution” and to form a three-sided square. The condemned were seated on their coffins in front of their graves at the open part of the square formation. The right knee of one of the deserters trembled slightly as he watched the procession approach to place the blindfolds. New ammunition was handed out to the firing squad who made ready to carry out the sentence. When all was ready for the brutal climax, the proceedings quickly degenerated into shocking incompetence. Of the sixteen guns in the squad only three discharged – faulty ammunition. Only one of the prisoners was hit and wounded. The other was not touched but from sheer fright, slid off his coffin “to his knees, slipped the handkerchief off his eyes and stared full in the face of the men who came up singly and put the muzzle of their guns to his head.” He could feel the heat of the barrel against his temple and waited for the blast. An instant of terror, frozen forever in time. Nothing happened, the first gun would not fire, only the cap detonated. Another man was sent and the ghoulish process repeated. No discharge! Once more and again, none fired. The victim was now reduced to a quivering mass of raw fear. Finally, the Provost Marshall “had to come up with his revolver to put the poor fellow out of his misery.” Meanwhile the firing squad had re-loaded to finish off the wounded prisoner who had lain dying while the circus unfolded. In a farcical denouement, after repeated firings at “the scene of butchery”, the prisoners were finally pronounced dead. By companies, the division marched “past the graves and the bleeding forms of the victims.” The new recruits of the 14th Connecticut received a special viewing of their own, after the division had passed. Perhaps the only consolation for the Nut-Meg boys was that none of their regiment formed the firing squad. A sergeant in the 108th New York simply wished “I pray God that I may never witness another such a scene.”39

For others, the respite on the Rapidan occasioned restlessness. Brigadier General Alexander Hays was not a patient man. He needed activity – craved action and excitement. Meade’s cautious probes, his careful approach to the lair of Mars Robert at Orange Court House and his apparent disinclination to engage the enemy, tried Hays’ patience - what little he had of it. Riding furiously up and down a battle line, perhaps a little drunk, with bullets flying, dragging the banner of a vanquished foe - that!,was action for the general of the Third Division. Meanwhile, Lee and Meade seemed to be involved in a strange pas de deux, choreographed around the rivers, the railroads and the numerous court houses in north eastern Virginia. Even Henry Halleck, in a rare outburst of aggression, urged Meade to attack Lee and “cut off a slice of his army.” But the offensive delirium soon subsided and Halleck, ever the lawyer, more characteristically added that he “did not think the exact condition of affairs is sufficiently ascertained to authorize any very considerable advance.”40 Meaning what? “Advance, but not too far? Attack, but not too much?” Rather than waste time while Meade digested Halleck’s equivocal advice and partly to alleviate his boredom, Hays decided that he would at least stir up the relative calm along the Rapidan.

During the sojourn by the river, Hays seemingly became enamored with a large white house which sat among a group of houses near the Rebel lines. In the Second Brigade, the regiments “were detailed to go on duty three days and nights in the lowlands opposite the enemy” and on the evening of September 25th, the 108th New York was on duty at the location of the house. With Lt. Col. Pierce on leave and no replacement for the retired Major Hogoboom, Colonel Powers, who had returned to the regiment early in September, was the only senior regimental field officer on duty. With typical flourish, Hays rode up and in imperial fashion demanded, “Powers, I want your regiment. There is a large white house over there in the Johnnie’s lines, which I think will make just the headquarters I want.” Now, why exactly Hays wanted a headquarters in the Rebel lines was never explained but Powers received the order and told the boys to “fall in and go.” As the men departed on their dubious mission, Hays added, “If we don’t take it, we’ll give ‘em a hell of a scare” which in reality may have been the real motive for the attack. Into the lowland area, four companies of skirmishers preceded the main body of the regiment. Soon the enemy pickets were driven in and the New Yorkers cautiously navigated the marshy land directly to the front of the settlement. Although the night was clear, when they scrambled over a fence they unexpectedly “landed in a ditch four or five feet in depth” and were quickly entangled in numerous weeds which grew higher than the ditch. All the time at their backs they heard Hays’ exhortations, “Charge, boys, charge, give ‘em hell!” The Rochester men double quicked towards the houses and sent the Rebel pickets flying. For some reason, they decided to torch the houses but only had time to fire one of them. Hays’ foray stirred up a hornet’s nest. As drums sounded the long roll along the entire Confederate line, the 108th New York, an under strength regiment, did not intend to hang around to confront the gathering enemy infantry but Hays had had his fun and took joy in the fact that his boys “scared em’ like the devil.” Jim Plunkett, sergeant, Company D, may have failed to see the humor since “he caught a red hot ball” that sent him to Campbell Hospital in Washington, D.C. for four weeks. Perhaps, the fun also was lost on the two men from Company E, who hid in the woods overnight, and were taken prisoners in the morning as they attempted to return to the regiment. The action lasted a little over an hour but really served no purpose other than ‘dung agitation’.41 For real action, Hays would have to wait another two weeks.

The prospect of action led to the early return of Dr. Francis Wafer from his twenty day sick leave. His leave was granted on September 7th just when he began to feel much better but was still ill enough to be treated. After a day long journey, Wafer arrived at the United States Hotel in Washington around 10p.m. where, thankfully, he was re-united with his trunk which had been left at the hotel some six months earlier. Immediately, he treated himself to some new undergarments and a clean shirt. The next day, he reported to the officer’s hospital where he was cared for at the rate of one dollar a day “board and treatment.” Over the following seventeen days, the doctor recuperated not only at the hospital but also in the bustling wartime capital. Daily, he was granted a pass to Washington and experienced the highlights of the city, sometimes in the company of Lt. Col. F.E. Pierce, who evidently did not have to wait until Christmas for absence. Officially Pierce was convalescing from general debility and chronic diarrhea, but in reality was awaiting approval for his request to visit home. Unfortunately, Wafer, who also longed to go home, was denied his request since he had not followed the proper procedure. Nevertheless, the two comrades spent time together visiting the Navy yards and the Smithsonian Institute. The doctor took in some plays, a bit of night life, but when he found out that the army was moving, he cut short his leave since he “could no longer honorably remain absent from my command.” Dr. Wafer insisted on being discharged from care even though the ward doctor, Staunton, “remonstrated with me on my expressing my wish to go back to the field, telling me that there was still a large quantity of fluid in the right pleural cavity and that it would be positively dangerous for me to expose myself to the chances of a relapse.” The doctor chose to disagree with his colleague since he felt that a return to active duty in the healthy air of the outdoors would be more beneficial. Also, in general he was not overly impressed with the capital and had grown “heartily tired of the city and was eager to join my command where life was more exciting”.42

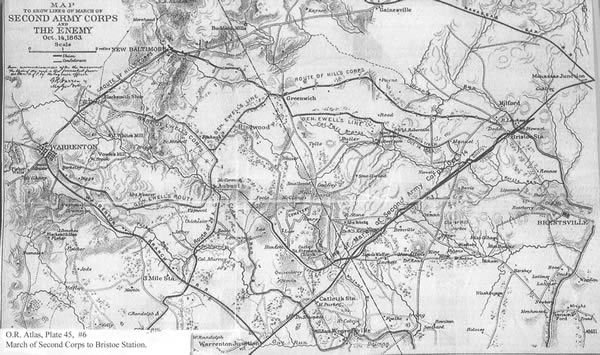

March of the Second Corps to Bristoe Station

O.R. Atlas, Plates 45, #6

The movement that the doctor heard of started in early October, 1863 but was occasioned when Meade’s army was reduced by approximately 16,000 men on September 24 as the Eleventh and Twelfth Corps were consolidated into the Twentieth Corps and sent west to aid Rosecrans who was surrounded by Bragg’s army at Chattanooga. With the end of September, Meade still observed the Army of Northern Virginia, encamped around Orange Court House, from a safe distance on the northern bank of the Rapidan River and showed little inclination to take the offensive. Since General Robert E. Lee habitually read Federal newspapers, he learned of the departure of the Eleventh and Twelfth Corps from the Washington Chronicle of September 25, 1863. On October 1st, Lee confirmed the depletion of Meade’s army and within days initiated offensive operations.43 Still unaware of Lee’s intentions, Meade ordered the Second Corps to be relieved by the Sixth Corps on October 6 and withdrawn to the area about one mile east of Culpeper and positioned across the tracks of the Orange-Alexandria Railroad.44 However the quiet routine of autumn on the Rapidan was broken when, a day later, the Signal Corps intercepted messages from J.E.B. Stuart to Fitz-hugh Lee that indicated Confederate activity. Once more, General Lee seized the initiative while Meade was forced to react.45

Lee intended to turn the right flank of Meade’s army, place himself between the Army of the Potomac and Washington and thereby force a battle at a place of Lee’s choosing. On the morning of October 9, the Confederate army crossed the fords of the upper Rapidan, west of Orange Court House and by “circuitous and concealed roads” through hilly terrain, attempted “to avoid the observation of the enemy” as they headed towards Madison Court House on Meade’s right flank. The movement was a classic flanking maneuver which Lee generally employed to avoid a full out engagement and to isolate portions of the enemy forces in order to overwhelm them in detail.46 Contrary to Lee’s wishes for security, the Richmond papers advertised the Rebel crossing of the Rapidan on October 10 but Meade, who did not consult newspapers, knew of the flank movement by 7.00 p.m. on October 9. Still, Meade could not determine Lee’s intentions. Was the move a feint to cover a “falling back from the Rapidan” or was it “a flank movement” against the Army of the Potomac “by way of Madison Court House and Weaverville.”? 47 Meade stood pat for the moment, watched and waited. At this point in the war, it was quite delusional to believe that Lee with a rested army of almost 50,000 men would voluntarily retreat without a fight. By 5:30 p.m. on October 10 as Confederate columns with long wagon “trains and accompanying beef cattle” moved through Madison Court House, Meade soon recognized the offensive nature of Lee’s movements. Despite the realization, Meade was still under the operational parameters

conveyed to him on June 27 when he was appointed to the command of the Army of the Potomac, specifically that he must “maneuver and fight in such a manner as to cover the capital and also Baltimore as far as circumstances will admit.”48 Since Lee was succeeding in his attempt to turn Meade’s right flank and interpose between the Army of the Potomac and the capital and since a significant part of his army could be isolated if he did not act, Meade had no choice but to withdraw beyond the Rappahannock and hopefully win the race to Centreville where he believed that Lee hoped to gain the high ground and force a battle.

The 108th New York and the rest of the Second Corps pulled out of their camp near Culpeper after midnight on Sunday, October 11, heading for Bealton Station, 18 miles to the east along the Orange and Alexandria Railroad. As the men of the Second Brigade in Hays’ Division trudged along the tracks towards Bealton, the approaching daylight revealed that the entire army was in motion and the movement was retrograde. The Second Corps bivouacked at Bealton around 5:00 p.m. on the 11th, with the other corps of the army within supporting distance.49 By that evening, the five corps of the Army of the Potomac formed a line from Freeman’s Ford, north of Rappahannock Station, to Kelly’s Ford on the south. From north to south, the corps in order were: Third Corps at Freeman’s Ford ; Second Corps from Freeman’s Ford to Beverly Ford; Fifth Corps from Beverly Ford to Rappahannock Station; Sixth Corps from Rappahannock Station to Kelly’s Ford and the First Corps at Kelly’s Ford. Cavalry screened the flanks and front of the army.50

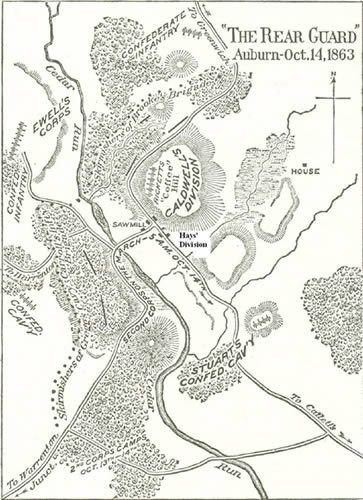

The Fight at Auburn Mills, showing Hays’ position on Oct. 14, 1863.

(Map taken from Walker’s Second Corps – see Bib. for full citation- p.330.)

The morning of the 12th, however, brought confusion to the otherwise smooth withdrawal. Francis Walker, the Second Corps historian, claimed that the foul up occurred when General Pleasanton of the Cavalry Corps and General Sykes of the Fifth Corps found Confederate infantry at Brandy Station, located a short distance east of Culpeper. Both generals concluded “that the Confederate army was really being directed upon Culpeper” and that Meade should reverse the movement of October 11, re-cross the Rappahannock and attack Lee at Culpeper which was exactly what he did.51 Unfortunately, neither Lee nor the body of his army was at Culpeper, in fact, while Meade was retracing his steps and moving west over the river early on October 12, Lee was crossing Sulphur Springs, north and east of Meade. In other words, the Rebel army was in Meade’s right rear and closer to Centreville than the Army of the Potomac. Meade was informed of his mistake around 10:00 p.m. on the 12th, so once more he ordered the army into reverse and back to its first course. The men, of course, were thrilled. A member of the Second Brigade wrote:

This was the eighth time the regiment had crossed the Rappahannock, in fact it would seem that crossing the Rappahannock had become a habit and that the troops were ordered back and forth over the river when the commanders could not think of anything else to do.52

Footsore, tired and hungry, the weary Union men shuffled along as the retreat continued on the 13th of October and Meade attempted to keep all the corps within supporting distance of each other. That night, the various corps of the Federal army bivouacked east of Warrenton, within 2- 4 miles of each other. The Third Corps was at Greenwich, about 3 miles northeast of the Second Corps at Auburn. Sykes’ Fifth Corps camped on Walnut Run, approximately 4 miles southeast of Auburn, while the Sixth Corps was 4 miles east of Walnut Run near Kettle Run and the lead corps, the First, was at Bristoe Station, 2 miles east of Kettle Run. As can be deduced from the corps positions on the evening of the 13th, the Second Corps was once again the rearguard of the army.53 To the west, Lee’s advance had stalled at Warrenton. A day earlier on the 12th, the Army of Northern Virginia marched out of Culpeper “in two columns with the design of reaching the Orange and Alexandria Railroad north of the river [Rappahannock] and intercepting the retreat” of Meade’s army. This was the mass of Rebel infantry spotted and misinterpreted by Pleasanton and Sykes. As Meade mistakenly advanced to Culpeper, Lee’s army had moved north and, after forcing a crossing at Sulphur Springs, General Lee and Ewell’s Second Corps reached Warrenton on the afternoon of the 13th. Hill and his Third Corps, had swung northeast out of Culpeper on the Sperryville Pike on a longer, more circuitous route and then turned east at Little Washington towards Warrenton where they arrived later that night, too late to continue the advance.54 Hill’s lengthy march effectively slowed down Ewell’s troops since Lee wanted his army united before he faced Meade and thus the Rebel forces did not progress much farther than Warrenton, where they bivouacked for the night.55

Lee’s flanking maneuver almost worked to perfection. On the 12th, his army was virtually in Meade’s rear and the Federals were backpedaling. Meade’s army made up the initial deficit of October 12 and, by rapid marching along parallel roads and O & A Railroad, was now just ahead of Lee in the race towards Centreville. The rearguard of the Federal army, the Second Corps, was, at most, only 4 miles east of Lee’s army. A Confederate artilleryman admitted:

Meade has so far managed pretty effectively, to keep out of our reach. It has been a long time since the battle of Gettysburg, and if Lee’s army was so badly whipped there, what makes Meade keep out of our way so carefully? He is not in a hurry to cross swords again.56

Lee maintained the two-pronged pursuit when his men exited Warrenton to continue the pursuit of Meade. The northern column or outside pincer, A.P.Hill’s Third Corps, moved out on the Warrenton Turnpike at 5 a.m. October 14 to New Baltimore “then took the road by Greenwich and on to Bristoe Station.” Once more, this was flanking movement trying to isolate a part of the Federal army. The second column, the inside pincer, used two roads from Warrenton that converged at Auburn. Fitz Lee’s cavalry and Early’s Division moved southwest along Double Poplars Road whereas Johnson and Rodes approached from the northwest via the Warrenton Turnpike and Dumfries Road. In actuality, Ewell’s advance on Auburn became a pincer within a pincer movement, a maneuver worthy of his mentor, Stonewall Jackson. After Auburn, Ewell’s march was to parallel that of Hill’s. Ideally, Lee hoped that both corps would arrive together at Bristoe and in time to maul Meade’s retreating army in detail.57 But a problem developed at Auburn.

Auburn or Auburn Mills or Auburn Hill had as many names as it did buildings. In October of 1863, Auburn was a “little hamlet consisting of the residence Stephen McCormick, a post office and a blacksmith’s shop.”58 On the evening of the 13th, Warren’s exhausted men bivouacked just south of Auburn in a wooded area west of Cedar Run on the Old Carolina Road from Warrenton Junction. They “dropped on the ground senseless from fatigue.” Even if they had been able, they could have advanced no farther since French’s Third Corps monopolized the available crossings of Cedar Run. “General Warren was well aware of the disadvantages of encamping, as he had done, on the south side of Cedar Run; but he had felt that there was no alternative.”59 Obviously, Warren was aware of the Rebel force at Warrenton which, as far as he could surmise was moving towards him and he did not relish the idea of being the only Federal corps south of Cedar Run, separated from the rest of the army. What he did not know was that Lee’s advance from Warrenton would not start until the next morning and that a Rebel force was already present on the opposite shore of Cedar Run. The Confederate troops belonged to none other than the flamboyant cavalier, J.E.B. Stuart, who inadvertently found himself sandwiched between the Union Third and Second Corps and unable to move his command back to Warrenton. Earlier in the day, Stuart was on a reconnaissance for General Lee to Catlett’s Station when he became enmeshed in this embarrassing situation and typically, the bold dragoon decided to hide in the midst of the Federal army. H.B. McClellan on Stuart’s staff recalled the entire episode as a mixture of high anxiety and ludicrous low comedy. The trapped cavalry brigades took refuge in the wooded hills around Auburn but were still close enough “to the marching columns of the enemy that we could distinctly hear the orders of the officers as they closed up the column”. During the long night of silent concealment when every errant bray of a rebel mule caused a ripple of consternation throughout his command, Stuart “dispatched six separate messengers (bold men) who were directed to slip through the enemy’s column” and to reach General Lee “with information of the state of affairs.” Major Andrew R.Venable, Stuart’s assistant adjutant, in the early hours of Oct. 14th got through to Lee, who directed the divisions of his Second Corps to assist the wayward cavalier.60

As Ewell’s force closed on Auburn, the Union Second Corps was up and moving by 4:00 a.m. When the they approached the crossing over Cedar Run the next morning, the men understood Warren’s concern and realized that their journey across the stream could be quite perilous since the ford was narrow and nearly surrounded by high, often precipitous, ridges and hills, especially to the northeast, where the night before they had seen Ewell’s campfires and the direction of his advance.61 The Old Carolina Road, between Warrenton and Warrenton Junction, snaked northward through the high ground along the western bank of Cedar Run then crossed the stream into Auburn where it t-boned with the St. Stephen’s Road that curved northeast to Greenwich and southeast to Catlett’s Station. Directly to the east of the t-junction, a large open hill on the eastern bank overlooked and commanded the crossing or ford. In the misty pre-dawn twilight, Caldwell’s First Division led the advance and, once over Cedar Run, his men deployed on the hill, facing northwest towards Ewell, thereby covering the ford for Warren’s two remaining divisions. Once settled on the hill, Caldwell’s men became seriously involved in the central chore of making breakfast. In a matter of minutes, the light from small fires broke through the heavy ground mist and smoke ascended straight up in the windless air. To augment the tranquility of the scene, sunlight began to highlight the open hill top in autumnal hues which, for a young New York officer, “made a picture not to be forgotten.” General Caldwell “was so impressed by the scene that for a time he refused to take his breakfast. He christened the place Coffee Hill.” In a less romantic mood since they were not allowed a bucolic respite, the men of Hays’ Third Division wearily followed the First across the run and then turned right at St. Stephen’s Road to Catlett’s Station. Barely had the Third Division turned onto the road than artillery shells began to scream over the heads of Hays’ men but landing in the rear of the First Division, completely destroying the pastoral illusion and creating havoc among the diners. Shrouded by the heavy mists in the stream valley, as well as the lack of full morning light, no one could tell from where the artillery fire originated, only that it was landing with “fatal effect, killing 11 and wounding 12.” One shell “exploded directly over a little fire, killing the four men outright who composed the group about it.” Blood now blended with the hues of autumn. The cannon fire from the rear combined with the musketry fire from the front and right flank created a moment of panic for the Second Corps since it appeared that they were surrounded.62

Of course, the party crasher was the plumed cavalier, whose two brigades of cavalry had remained undetected, hidden among the hilly woods a few hundred yards south of Coffee Hill. That morning, Stuart placed his artillery pieces on a hill, just east of his hiding place. When he heard the musketry from Ewell, he “opened seven guns upon the enemy and rained a storm of canister and shell upon the masses of men, muskets and coffee pots.” The predominance of references to the upset coffee pots in the accounts of the attack suggests that Caldwell had indeed named the hill appropriately.63 Hays, who was initially surprised by the attack since he believed that the road to Catlett’s Station was under Union control, responded quickly. Smyth’s Second Brigade deployed the 108th New York, the rear regiment, to cover the right flank and the 1st Delaware, the lead regiment, to cover the left flank of the column. The 14th Connecticut was held in line of battle while the 12th New Jersey joined the 126th New York from the Third Brigade, which led the division, to move forward and assault Stuart’s position. A short, “but very decisive” engagement ensued, during which the 1st North Carolina cavalry charged the 126th New York “and were most gallantly repulsed, with the loss of their leader, who was mortally wounded.” A New Jersey officer wrote that, once confronted, the Rebel cavalry ran “like mad in every direction, some even ran into our provost guard in rear of the Division.”64

J.E.B. Stuart, as expected, reported the attack of the “Old First” North Carolina with a different spin. The beau sabreur claimed that the “gallant colonel (the lamented Ruffin) charged a regiment of infantry nearly all of whom had surrendered [my emphasis], when a re-enforcement closing up rapidly under the cover of a fence compelled this Spartan band to relinquish their captives.”65Stuart, perhaps the first media star, whose report was in the Richmond papers about ten days later, always had a tendency to visualize his engagements in mythic or epic terms (Spartan-North Carolinians?) and to downplay setbacks as simply minor snags in strategy. Consequently, his claim of a surrendering ‘regiment’ may be without substance, however the initial skirmish line sent out by Hays, five companies of the 125th New York were repelled but by dismounted Confederate cavalry and the New Yorkers “ran like sheep to the rear” due to the alleged “chicken heartedness” of Major Samuel Armstrong. A modern historian implies that the regiment under duress was the 126th New York and their rescuers were the men of the 12th New Jersey.66 Since Stuart never clearly identifies the regiment nor its state designation, the details of the episode remain murky. But both of the New York regiments involved suffered from the stigma of the previous year when they were surrendered at Harper’s Ferry and labeled ‘cowards’ so any attempt to surrender by either regiment may well have been downplayed or overlooked. Or, more simply, did Stuart’s penchant for dramatic vignettes get the better of him?

In the midst of the uproar on the St. Stephen’s Road, Dr. Francis Wafer watched with bemused detachment the plight of the “non-combatants, including hospital attendants, servants and numerous men to be found in an army that manage to keep out of most fights.” The doctor noted that since there was no rear to run to – they thought they were surrounded – these people resorted to ludicrous measures to avoid being under fire and some were picked up by Stuart’s horsemen in their vain effort to exit the scene of action.67 For a change, the 108th New York was a spectator and suffered no loss of life. When the fight was over, Chaplain Thomas Grassie went out to the Rebel wounded to provide whatever comfort he could. Here he found Colonel Thomas Ruffin, the wounded leader of the 1st North Carolina Cavalry. The wound was mortal and Ruffin knew it but as he spoke with the chaplain, the colonel explained that he “had handed to a Union sergeant a gold watch and money” and asked if Grassie “would find the sergeant, get the watch, and send it to his relatives as it was a valuable heir-loom.” Thomas Grassie realized the futility of such a request and did little to comfort the dying ex-Congressman from North Carolina when he told him “that there were so many sergeants he did not know where to look for the one who had his watch.” Actually the spiritual leader of the 108th New York did not have to look any farther than the 12th New Jersey since Sgt, Henry Avis of Company F found Ruffin shortly after he fell and noticed beneath the colonel “ a very fine gold watch and chain, partly exposed.” Whether Avis got the watch or not was not clear but while he and other comrades of the 12th New Jersey stood around the wounded officer, one of them politely said, “Colonel, do please hurry up and die; we want that watch.” The Colonel died four days later in Alexandria, Virginia, watchless and chainless.68

Stuart’s interference caused some delay for the Second Corps but the quick disappearance of the Rebel cavalry also led to relief for Warren who believed that he was about to be attacked on every side. Hays finished dealing with Stuart and no “sooner, then did Hays report the way open than Webb, with the Second Division took the advance to Catlett’s.”69 The march continued northward to Centreville via Catlett’s and Bristoe Stations, with Caldwell’s division acting as the rearguard of the corps, which functioned as the rearguard of the army. Meade instructed each corps commander to keep within supporting distance of the corps that followed. For example, the Third Corps should not advance until the Fifth Corps came up who, in turn, should not advance until the Second Corps came up. “By this arrangement it was expected to have three corps available, if required, to meet any force of the enemy that might be encountered.”70 Warren’s temporary delay during the early morning hours at Auburn caused a problem for Meade’s accordion-like march. On the morning of the 14th, the First and Sixth Corps were probably at or very near Centreville, while the other three corps were still moving to the rendezvous. Apparently George Sykes, the commander of the Fifth Corps, sandwiched between the Third Corps and the Second, began to panic while waiting at Bristoe Station for the delayed Second Corps to appear. Earlier, Major General Judson Kilpatrick had erroneously reported that Lee’s infantry were “moving on the Warrenton pike,” evidently Centreville as their destination. The Warrenton Pike, an east-west thoroughfare between Warrenton and Centreville, was located to the north of Bristoe Station and no where near the Orange and Alexandria Railroad on which the station was located. Therefore, as far as Sykes was concerned, he was wasting time at Bristoe waiting for Warren and should be backpedaling to Centreville. Sykes had no idea that A.P.Hill’s Corps turned southeast off the Warrenton Pike and were moving via Greenwich towards Bristoe Station. As the morning seemed to drag on, Sykes became more and more impatient. Shortly after 2:00 p.m., Sykes’s aide-de-camp, Lt. Snyder, mistakenly informed him that the Second Corps was approaching and Sykes, without bothering to verify the information, immediately packed up and headed for Centreville which left the Second Corps to face the forces of A.P.Hill and, perhaps Ewell, on its own.71

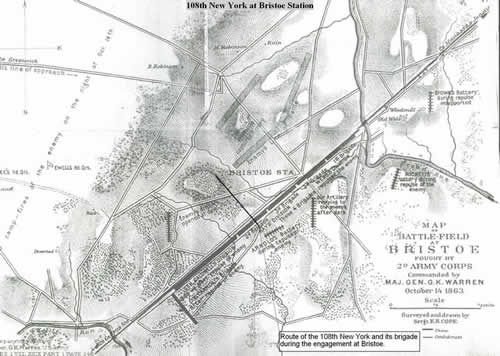

Bristoe Station on the O&A Railroad was about 2 miles southwest of Manassas Junction, which was 8 miles south of Centreville. For the most part, the area around the station is plain but the track cut northeasterly through woods and hilly areas that created an embankment on the north side of the railroad. The Federal Second Corps arrived at Bristoe shortly before 4:00 p.m. but Hill’s Third Corps were already on the high ground around the station about one hour before the arrival of Warren’s lead division. At first, Little Powell had his eyes set on the receding columns of the Federal Fifth Corps on the northern side of Broad Run, which he inaccurately believed to be French’s Third Corps. “Seeing this General Heth was directed to advance his line until reaching the run, and then to move by the left flank, cross at the ford and press the enemy.” Hill was in a hurry to catch and destroy some part of Meade’s army so he ordered the advance of Heth, even though the division commander “had not quite completed the formation of his line.” No time was taken for reconnaissance and, in the early stages of the engagement, no one seemed to notice the approach of the Warren’s Corps on the other side of the embankment along the railroad on the exposed right flank of the Confederate line. With Webb’s Division in the lead, followed by Hays’, the Second Corps advanced to the sounds of Poague’s artillery “opening on the rear of the Fifth Corps.” Webb’s Division engaged the Rebel force by seizing the area around the ford over Broad Run, south of the railroad bridge. Warren quickly realized that the railway embankment was the key to the battle and ordered Webb “to hold the railroad embankment” near the run. Hays’ Division, which had been hidden by woods from the sight of the enemy, was told to face left “and run for the cut” on the other side of the woods. Within minutes, the Federals would have control along the entire length of the railway cut. Suddenly, Hill realized the cost of his impetuosity when Heth’s men began to receive flank fire from the growing line of Second Corps rifles, protected by the embankment. He swung the brigades of Kirkland and Cooke to the right and advanced towards the Union line in an effort to gain the position along the railroad before the Union army. Initially, as the two Rebel brigades were advancing toward the embankment, they were met only “by the fire of General Webb’s men whose line of fire was much shorter than that of the enemy” who, if they reached the embankment, would outflank the Federals.72

Nearly one mile from the station the 108th New York heard the engagement of Webb’s troops and moved at the double quick towards the gun fire. As Hays’ Division advanced to the aid of Webb, a number of men could not keep up, so the line of advance lengthened. Some regiments became intermingled and went into the conflict “in any order” but military. Such was the rush of troops that stragglers from the lead division as well as those from the Fifth Corps were swept up in the flow and propelled, much to their chagrin, into battle. Officers struggled to maintain some degree of order and to form a coherent line of battle as they raced towards the railway embankment. General Warren and his staff on hand to personally urge the men: “To the railroad ditch, men and quick! quick!” Hays, on the other hand, before his troops could align properly, charged with his men through the woods to the ditch and opened on “the rebel infantry which was advancing about 300 yards from the railroad over a field.” As each Union regiment arrived, the battle line along the embankment lengthened until, when Hays’ men arrived, the line overlapped the Confederate forces.73 After the repulse of the first Rebel charge, General Hays decided to take advantage of the longer Union line. He ordered the Second Brigade, under Smyth, forward over the embankment and through a wood to the left of the division in order to flank the enemy column to their right front, which was probably the remnant of Cooke’s Brigade.74 With the 108th New York at the extreme left, then the 12th New Jersey, the1st Delaware and finally the14th Connecticut on the right, the Second Brigade moved forward. Hardly had the advance begun when the 7th Michigan of Webb’s Division, who had been deployed as flankers, squeezed into the gap between the 108th New York and the 12th New Jersey. The gap developed because the regiments were brought hastily into line and the formation of the 108th was hampered by “straggling skirmishers” from Webb’s Division who misled Colonel Powers as to the location of the brigade left. Once the gap was rectified the Second Brigade resumed the advance on the plateau beyond the railroad cut. They moved through the wooded area to its farthest edge which opened on the expanse of the plain at Bristoe Station. As they emerged from the woods, Smyth’s men spotted a Rebel battery of five guns, three from the 2nd Rockbridge Artillery and a section form Hurt’s Battery, located on a hill to the right front with a field of fire that commanded the railroad and the station. By the time the 108th New York arrived at the clearing, Heth’s infantry had been routed and the battery was left unsupported but the energetic Hays had already sent a skirmish line consisting of the 111th and 125th New York from Owen’s Brigade, augmented by skirmishers from the 19th Massachusetts, to overrun the five guns of D.C. McIntosh’s battalion.75 Meanwhile, Powers noticed “a formidable body of the enemy”, the division of Richard Anderson to the left front, and “perhaps 500 yards distant.” One or two of the New Yorkers were dropped by fire from this Rebel column so Smyth ordered the 108th New York, the 7th Michigan and two companies of the 12th New Jersey “to file to the left to meet the enemy threat.” With the left of his brigade occupied by Anderson, another Rebel line advanced diagonally across Smyth’s front, presenting its flank to the Federal Brigade. They opened fire and stopped the Confederate brigade in its tracks. For a while, the Second Brigade held its position at the wood’s edge then was ordered back to the safety of the railroad embankment. For all intents the battle at Bristoe was over.76

Just after 4:00 p.m. when the battle started, the medical men of the Second Corps began to search for a hospital site. Uncharacteristically, Francis Wafer was separated from his regiment and was not present on the firing line during the engagement. Instead, he remained in the rear area with the immense wagon train. However, the rear area also provided lively entertainment once the wagon train became a prime target for Confederate artillery and cavalry. At one point, Dr.Wafer and Dr. Alvin P. Satterwait, Chief Surgeon of the 12th New Jersey, seemed to be primary targets for some Confederate guns. Shells flew over about them and exploded around them. One Rebel gunner in particular must have thought he was firing at general officers since a fused shell burst over the heads of the medical men and a percussion shell that went screaming between their horses exploded on impact with the ground. Both surgeons gave up any attempt to observe the action once the inevitable wounded began to arrive. To find an appropriate spot for the division hospital, with adequate water and suitable space for operating, but out of artillery range, became a difficult exercise. At first, a barn, near Kettle Run and about 1½ miles in the rear, was selected. The medical men “had not more than fairly commenced operations than the rattle of carbines was heard in the woods” about ¼ of a mile away. Rebel horsemen, attracted like flies to the wagon train, were soon controlled by Gregg’s cavalry but the doctors decided to move again – almost the prototype of a MASH unit. Rifles, carried in by the wounded, littered the ground around the barn. Some surgeons picked up the discarded weapons to arm themselves, while others threw them in the creek. Wafer chose to defend himself with “a few rounds of ammunition” in case “it might become necessary to scare enemy cavalry.” Twice more the battlefield healers moved their facility to avoid the twin plagues of carbine fire and artillery shells.77

At sunset, the surgeons were ordered to report to their units, but Wafer refused to depart until the wounded of the 108th were sent to safety. Chester Kenyon of Co. K was the only fatality in the regiment, with over a dozen enlisted men wounded. Lt. Sam Porter, who a month earlier expressed such disgust at southern life, was the only officer to be wounded, a severe wound in the left leg that would keep him out of action until early 1864. Sergeant William H. Plummer of Co.A also suffered a wound to the left thigh which eventually took him out of the war completely. Oddly enough, nearly all the other twelve wounded were hit in the legs. Wafer theorized that since on two occasions during the battle the men passed through thick copses of brushwood only their lower extremities would be visible to enemy riflemen firing from the prone position and since the line would be moving slowly through the bush, more time was provided to pick targets, in this case, the legs. The predominance of such wounds created a further problem for the doctor. Most of the men were non-ambulatory and required transportation, but “no ambulances were present” except “those that had been detailed to follow the Brigades on the march.” Since the majority of ambulances was with the army wagon train and could not “come so far from the train without risking capture”, the few available ambulances were rapidly filled and as rapidly driven away. Those unable to walk began to fear that they would be left behind to either die or face a Rebel prison which quite often meant the same result. Wafer worked against time now but persevered in his resolve to remove all the wounded Rochester men and when he had “seen all safely loaded, I started for my regiment with pride and the highest degree of gratification that I could say not one of the 108th was left on the field.”78

Darkness fully descended while the 108th New York maintained its vigil in the railroad cut. The night was so black that Dr. Wafer found his command almost by touch as he “grasped” his way down the Union line. In the inky night land and sky merged and thousands of Confederate campfires began to appear, flickering like distant stars, almost surrounding the northern troops. A.P.Hill and now Ewell were out there, waiting, hoping to pounce in the morning and bring the full weight of two Confederate corps against the under strength Union rearguard. Warren had no intention of facing the combined southern force so shortly after 9:00 p.m., the 108th New York with the rest of the Second Corps began to withdraw towards Centreville. Silently, like shadows, the New Yorkers slipped into the darkness and away from the railroad embankment. The cacophonous cries of the Rebel wounded – “Help me, for God’s sake, don’t leave me here to die”- hung forlornly in the autumn night air then were drowned by the rumbling burden of artillery fire as frustrated Confederates shelled the phantom Union line. At Broad Run, the 108th moved “in Egyptian darkness”, clambered “down slimy, rocky banks” forded the stream and “up rocks again” until they struck the railroad line which they could follow safely to Bull Run.79 As the night of October 14 passed into the early hours of October 15, Warren successfully disengaged from the Rebel force at Bristoe Station and rejoined the Army of the Potomac deploying at Centreville. Before Lee could coordinate an attack with Ewell and Hill, Meade retreated to Bull Run and began to fortify his position. The Confederate commander realized that the proximity of the fortifications around Washington and Alexandria rendered useless ant attempt to turn Meade’s new position since the latter “could readily retire to them and would decline an engagement unless attacked in his fortifications.” For the present, Meade had won the race. Lee’s army moved back to the Rappahannock River and left Stuart’s cavalry on Meade’s front.80