Chapter Five

Rochester's Forgotten Regiment:

The 108th New York In The Civil War

By Terence G. Crooks

Chapter Five:

The 108th Is Only A Name Now

Around 3:30 on the afternoon of May 5,1863 rain began to fall on the battlefield of Chancellorsville. The men of the 108th New York had no shelter tents. To gain some relief, as the drizzle became a downpour, the New Yorkers wrapped themselves in their India rubber ground sheets.1 Over the previous two days, Francis Wafer, the regimental surgeon, tended the wounded at the field hospital. The word ‘hospital’ was a label only since the facility consisted of “pine boughs supported on forked sticks driven into the ground" to provide shade for the wounded. As he moved from patient to patient, he took time to move the more mobile to avoid the artillery shells that "fell thick and fast among the wounded”. Others simply "dragged themselves" out of the way. In an effort to triage, the more severely wounded were removed to the rear, near Kalmbach’s Sawmill on United States Ford Road. On the night before the withdrawal, Wafer had the midnight to dawn shift at the hospital. He had been unwell when he entered the campaign but now he was "well nye prostrated" with illness and lack of nourishment. Surrounded by the human suffering, Wafer did what he could during the hours of darkness. Quench a thirst, cool a fever or inject anodyne to those who suffered pain. Captain Thomas Stevenson, Co. ‘G’ of the 8th New Jersey, part of Berry’s Division which the 108th supported, had been shot in the abdomen - gut shot- and was going to die. Wafer could do nothing for him, but was so exhausted and ill that he

laid down near him that I might be able to give him a drink occasionally or change his position. The place was too open for lights, such as we had, candles, to be kept burning. His condition could only be known by my feeling his pulse. Towards midnight and not hearing him breath (sic) as usual I reached over and felt for his hand from where I lay and found he had departed. Some perhaps would have removed to another place but as I was then almost indifferent to life or death myself and saw nothing repulsive in the inanimate form by my side so I slept by it soundly until morning.

The young captain joined others who had ended their struggles, "their calm ghastly features painfully distinct, even in the darkness."2

As the dull grey light of dawn filtered through the drizzle, the doctor stirred beside the lifeless body of Captain Stevenson. Gradually, he realized that he was the only medical person present and that his fellow surgeons, Ely and Munson, had more or less abandoned their ailing colleague on the south side of the Rappahannock river while they had taken the opportunity to retire safely to the other side of the river and far from the front. Later in the day, the order was issued "for the Surgeons at the field hospital to join their regiments." A tremendous storm started as Wafer attempted to saddle his horse and the torrential rain only added to the frustration of the sick doctor. Finally, through sheer serendipity, he "succeeded in straying into the regiment" and literally bumped into Lt. Col. Pierce who advised him to precede the regiment across the river. Wafer heeded the advice. After a harrowing crossing on a pontoon bridge, the doctor found shelter for the night in a pine thicket. As luck would have it, when he awoke the next morning the 108th New York was passing so he joined his comrades’ march which continued until Falmouth was reached. In camp there must have been an awkward and embarrassing reunion of the medical profession. Dr. Ely and Chaplain Grassie had arrived 24 hours before the regiment, perhaps under the impression that their services were not required for the dead and dying. Dr. Munson was nowhere to be found since his personal retreat took him several miles beyond Falmouth. Wafer, in his diary, maintains the professional high ground and makes no comment about his medical colleagues. No sooner had he arrived in camp than he was ordered to duty at Potomac Creek Field Hospital where he remained until early June.3

When the 108th and the rest of the brigade returned to camp at Falmouth, numerous theories abounded about the recent setback. The most popular version placed all of the blame on "the panic of the Germans" of the Eleventh Corps. The rain was blamed; Sedgwick, for whom the task was too big, was also blamed. Inadvertently, Corporal Fletcher Thrasher of Co. ‘F’ did assign the blame where it belonged. In his defense of General Joe Hooker, Thrasher claimed that the "only thing I blame the general for was that he did not get the 40,000 troops, lying in reserve" into the fight and "sweep Jackson’s troops from the face of the earth."4 Such a claim may be simplistic and naive but Fightin’ Joe did repeat the error of the previous leaders of the Army of the Potomac. Unlike Lee, who never balked, Hooker refused to risk his entire army to gain a crushing victory and as a consequence he was "simply out Generaled".5Nevertheless, the ever-resilient Federal army re-grouped in their Falmouth Camp and prepared again.

On the Sunday after the defeat at Chancellorsville, the men of the 108th New York returned to camp from picket duty at about 10:00 a.m. The day was beautiful, a splendid spring Sunday. Dress parade was followed by a sermon from Rev. Thomas Grassie. Formed in a hollow square around the Chaplain and the men of the regiment listened, some intently, some not. Thoughts of mortality and after-life were common now, especially with the hell-fire of Chancellorsville still vivid in their minds. They realized the vulnerability of flesh and how quickly life can be snuffed out. Young but no longer invincible,the innocence of youth was gone, a memory lost forever at the Bloody Lane of Antietam or on the plain of Fredericksburg or now at the crossroads in Chancellorsville. At 3:15 p.m., while the Rochester soldiers reflected on the words of the Chaplain, and approximately 15 miles due south at Guiney Station, Lieutenant General Thomas J. Jackson of the Army of Northern Virginia, wounded a week earlier, died on the Sabbath, as he had wished.6 Rev. Grassie’s sermon did not last long and afterward the band of the 14th Connecticut serenaded Colonel Charles Powers of the 108th New York long into the evening of that beautiful Sunday of May 10,1863.

The remainder of the month was spent in drills, picket duty, mounting guard and dress parades but two significant changes did occur while the army waited. Shortly after the return to camp, the 1st Delaware, the only remaining regiment of the disbanded Third Brigade, joined the 108th New York in the Second Brigade to replace the 130th Pennsylvania whose enlistment time had expired. Since Thomas Smyth of the 1st Delaware was now the senior colonel and since General Hays was still in the hands of the enemy, the colonel took command of the Second Brigade.7 Early in June, the Second Corps also received a new commander. Darius Couch " had felt outraged in every nerve and fibre of his being, by the conduct of General Hooker" during the entire battle of Chancellorsville and his "distrust of Hooker’s capacity for high command was profound and unconcealed". Immediately after the battle, Couch requested a leave but was denied. He then asked to be relieved from the Army of the Potomac. Couch left the Second Corps on June 10, 1863 to assume command of the Department of the Susquehanna on June 11th . Major General Winfield S. Hancock assumed command of the Second Corps upon the departure of Couch.8

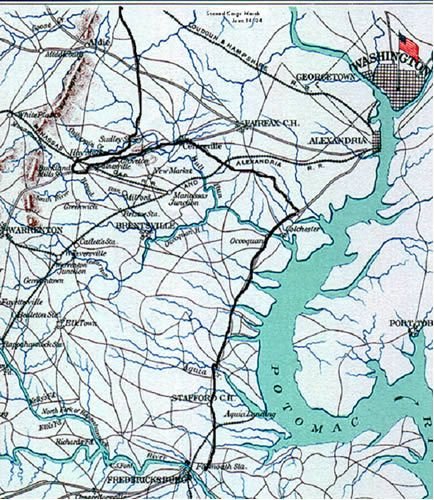

Camp routine resumed until the night of June 14th when the army began to move north in pursuit of Lee who had once again seized the initiative and started his army northward to begin what would become the Gettysburg Campaign. The men were told to destroy and bury anything that they no longer wanted to keep. At 9 p.m., the corps moved north along the Telegraph Road out of Falmouth and continued all night until a halt was called near Stafford Court House around 6 a.m. on the morning of the 15th. The Peck brothers, William and Willard, both of Company A, wandered from the rest area in search of water. The day was already warm and threatened to become hotter and the dust was already a problem. William was the elder, as well as a corporal, so he led the way to the nearby spring. They were out of range of the regiment so the enlisted brother could act freely with his corporal sibling. At the spring, they enjoyed the cool, fresh water, splashed some on their faces and began to fill their canteens. Suddenly a number of semi-uniformed individuals appeared with rifles and sidearms and claimed the brothers as prisoners of war. They could have been Confederates, probably deserters, but they called themselves guerillas as they marched the Pecks “about a mile and a half, in a direction away from” the rest stop of the 108th New York. The brothers were ordered to stop, kneel down and face away from the guerillas. Both were shot in the back of the head. Meanwhile the rest of the regiment ate breakfast "rested half an hour" and "marched to the court house" where they "formed a line of battle one-half mile south of it.” Since straggling was part of any march, the absence of the Pecks was not really noticed At this point the division picket which included Dr. Wafer rejoined the corps. Eight days earlier the Canadian surgeon had returned to the camp at Falmouth but was once more detached to serve on division picket duty, the purpose of which was to cover the withdrawal of the Second Corps from the Fredericksburg area. On the afternoon of the 15th of June, after an all night march, the division picket met the corps at Stafford Court House. The Second Corps left the court house, "crossed Acquia Creek at 4 p.m. and camped for the night".9 The next three days involved some strenuous marching as the corps maintained a northward march through Dumfries and over Wolf Run Shoals on the Occoquan River. On the 17th, the corps turned slightly north westward on Wolf’s Ford Road and bivouacked just west of Fairfax Station. It was here that General French returned to his division.

The 108th New York spent the entire day of the 18th near Fairfax Station. The next morning, before he could take part in the march to Centreville, Wafer was detached and “put in charge of an ambulance train containing 36 sick” men, bound for Fairfax Station three miles away. The trip was badly delayed so the ambulance train did not arrive at the station until “a late hour”. A further complication occurred when a medical officer could not readily be found to accept the transfer of the patients. Nevertheless ,the doctor persevered and as night set in, he started back to find his regiment. His decision to leave led him into a harrowing and strange experience.

When he left Fairfax Station, the doctor “did not order the Sergeant in charge of the train of ambulances” to wait for him. Consequently, he was left behind and, like the poet Dante, Wafer soon found himself “alone in a dark wooded road” with “a cloudy dark night setting in.” Even though the condition of the road restricted speed to a walk, the doctor and his horse glided silently through the growing darkness. He was completely alone on a moonless road and vulnerable. Thoughts of guerillas, deserters, stragglers, murder and robbery began to cloud his mind as well as stories of men who had fell out of a march and were never seen again. While these thoughts played in his imagination, he was startled to awareness when he “discerned two figures furtively moving in a contrary direction to mine.” They purposely stayed off the road “as they were moving through a piece of lately burned woods.” In order to portray confidence Wafer called out boldly “Who goes there” but the answer was not clear. He thought that he heard “Pennsylvania Reserves” but was unable to determine for sure .Nevertheless, he maintained his brave demeanour and “all parties went on their way” as the doctor made “the best time a walking horse was capable of making to our old camp.” When he arrived at the camp near Fairfax Station, he had no idea that the Second Corps had departed northwestward to Centreville.

Wafer “dismounted and searched the ground cautiously for marks of hoofs and wheels” which were numerous but gave no idea of direction. He concluded to follow in the direction of the previous day’s march, hoping to somehow re-join the Corps. As he continued along his course in the encroaching darkness, he perceived a horse “which stood some twenty yards from the road surrounded by some small trees.” Approaching the gateway “that led to the house - something like a horse appeared” and before the doctor could be sure “a mounted man” bolted “into the road”. The mysterious rider spoke not a word but rode off “in the direction of my march” only to stop at a wooded area about 100 yards down the road. Wafer hailed the rider, thinking he was a straggler. No answer. As the doctor neared the wooded area, he again invited the rider to join him. An inadvertent “movement of his horse’s foot” revealed to Wafer that the stranger “was lurking in the bush but a few yards from the road.” The surgeon of the 108th tried a new ploy. He called to the listener in the shadows to “‘come along with us’ using the word us to cover my loneliness and weakness from detection.” The doctor could almost feel the blackness, like a palpable entity, just beyond his limited field of vision. He could no longer see his horse’s ears so allowed the animal to lead, hopefully away from potential danger. The gambit seemed to work since Dr.Wafer saw nothing further of the rider. Moving on through the intense darkness, the doctor became resigned to the fact that “no mortal could find me so taking a small bag of steamed oysters, which was opened with my pocket knife, and a piece of bread from my saddle bags, I managed to make a comfortable supper.” After a harrowing night spent huddled against the root of a tree, complete with thunder, heavy rain and lightning, the surgeon spent the night in “occasional snatches of sleep” until the morning of June 20th. With the help of a citizen, he re-acquired the trail of the Second Army Corps and discovered that he had spent the night only two miles from the camp. He rejoined his regiment and the Corps at Centreville, some 30 miles from Washington, and later in the morning marched westward on the Warrenton Turnpike toward the Bull Run Battlefield.10

March of the Second Corps June 14-24, 1863.

(O.R. Atlas Plate 22 no.5)

As they crossed the desolate field of battle, the men of the 108th could not help but notice their unburied brothers-in-arms. Some bodies had been rooted out of the shallow graves by hogs. Others appeared to have never been properly interred since the “only attempts at burial being the mere hiding of the body by heaping some earth upon it with a shovel where it lay.”11 The men were fascinated and repulsed by the spectacle of the dead. Two “perfect” skeletons were found, “one of which had been apparently a wounded soldier on a ‘stretcher’, the canvas of which had rotted away, leaving the nape of the neck laying across one of the cross pieces”. The “other skeleton was in a gully, the upper portion of the frame resting against one bank and the limbs from the hips upon the opposite bank.” Further on, they “counted ten skulls and Federal uniforms enclosing the bones of men”, but soon their fascination turned to anger when amidst their unburied comrades, they discovered the grave of “two confederates” with a” neatly lettered” request to “please don’t disturb them.”12

The march continued along the turnpike until the Corps reached Gainesville, about 15 miles west of Centreville. Here, the 108th with the rest of French’s division remained for the next four days but there was very little rest as the men were regularly called out with false alarms. From the 20th to the 24th Andrew Boyd, captain of Co.’H’, noted routinely in his diary: “Up at 3:30 a.m.; stood in line half an hour, stacked arms and went to bed.”13 While the 3rd Division encamped at Gainesville, the 1st and 2nd divisions, Caldwell’s and Gibbon’s respectively, continued through Haymarket to Thoroughfare Gap in order to feel out the intentions of Lee’s army and to act as the rearguard for the Second Corps, which in turn was the rearguard for the army.14 During the stay in Gainesville, the 3rd Division officially lost its long time commander, General William Henry French. Evidently, ‘Ole Blinky’ felt that his rank necessitated “a higher command” and, for a while, Hancock considered re-shuffling the Second Corps into two divisions, instead of three, in order to create a larger division for French but, the problem was solved when General French was assigned to command the garrison at Harper’s Ferry, some 11,300 men present for duty.15 On June 23, the 108th New York parted company with their division commander who had led them into battle since Antietam and were put under the temporary command of Brigadier General Samuel Koseiuszko Zook, who would die 9 days later, around 5 .p.m. in Rose’s Wheatfield at Gettysburg.16

Hancock received orders on June 25th to move away from Thoroughfare Gap and to proceed north to Edward’s Ferry.17 Unfortunately, just as Hancock was withdrawing, Jeb Stuart launched his raid through Glasscock’s Gap and caught Hancock’s rear division, Gibbon’s, as it moved eastward through Haymarket. Stuart opened with artillery fire on the Second Corps unit. The flamboyant cavalier typically inflated the effect of the attack “scattering men, wagons and horses in wild confusion” but Gibbon recalled no such upset. Other Federal officers remembered the attack as an “annoyance” since Fitz Lee’s brigade moved on Gainesville which temporarily isolated Zook’s command, including the 108th New York. Earlier that morning, Hancock had ordered Zook to be “in readiness to move at a moment’s notice to Gum Springs via Sudley Springs, northeast of Gainesville.18 Because of the presence of Confederate cavalry on his front, Zook eventually withdrew his command about midday on June 25th, eastward from Gainesville, retracing the route along the Warrenton Turnpike in the midst of heavy rain which continued all day. Just how the 108th New York and the rest of General Zook’s command moved to Sudley Springs is not clear. Since the First and Second Division of the Corps were already in motion eastward along the road between Haymarket and Sudley Springs, and since the rearguard of the corps had been attacked by Rebel artillery, it is doubtful that Zook would move towards Haymarket. Furthermore, his mounted pickets on the Warrenton Pike, west of Gainesville, were driven in and pursued by Stuart’s horsemen so Zook had no idea about the size of the force confronting him.19 To get to the Springs, Zook had two possible avenues. Four miles east of Centreville on the Warrenton Turnpike, the Pageland Road ran northeast to the Haymarket Road which it intersected about three miles west of Sudley Springs. His second choice was to take the road between Groveton and Sudley Springs which ran to the north from the pike about seven miles east of Gaineville and intersected the Haymarket Road approximately three quarters of a mile west of the Springs. There is no evidence to indicate if one or both roads were utilized by Zook’s command but it would seem that Smyth’s Brigade probably took the Groveton-Sudley Springs road. Dr. Wafer noted in his diary that the road passed through an open oak forest in which human remains still lay and “was near a place called Groveton.”20The doctor was

particularly struck by “a skeleton hanging doubled over a fence, no portion touching the ground

when the man must have been killed outrightly in the act of climbing the fence - or else his body placed there through inhuman sport.” Zook’s Brigade plus his inherited division crossed Sudley Springs Ford and paused for an hour to give some relief to the troops. As the soldiers did their best to relax in the driving rain, an orderly from Hancock arrived “with directions to proceed at once to Gum Springs and there join the rest of the corps.” The men moved out again but took the wrong road which caused a “considerable delay” and were forced to move cross country in order to find the proper road to Gum Springs. That night, at approximately 11 p.m., the 108th New York encamped south of Gum Springs, near the Little River Turnpike and the rain continued. Captain Andrew Boyd noted, with mild understatement, a “rather moist night for us.”21

At Gum Springs, French’s old division acquired a new brigade as well as new division leader. The new brigade was a an all New York unit, comprised of the 39th (the famous or infamous Garibaldi Guards), the 125th, the 126th and finally the 111th. These troops had the distinct sobriquet of “Harper’s Ferry Cowards” since they were part of the force surrendered by Colonel Dixon Miles to General T.J. Jackson at Harper’s Ferry nine months earlier. Their colorful brigade leader was Brigadier General Alexander Hays, a close friend of General Hancock but no relation to William Hays, the former leader of Smyth’s Brigade. Alexander Hays, like Hancock, was a Pennsylvanian and a graduate of West Point, class of 1844. In the war with Mexico, he was brevetted for gallantry but chose to resign in 1848 to pursue a career in the iron business. The iron venture failed so Hays quested after gold in California. He returned to his native state and became a “construction engineer specializing in bridge building in Western Pennsylvania.” When the war arrived, Colonel Hays led the 63rd Pennsylvania Volunteers and was severely wounded at Second Manassas. He received his first star shortly after in September of 1862 but did not see action again until June 1863 when he was assigned to Hancock’s Second Corps. On June 25th, when Hays’ New York Brigade became the 3rd Brigade of the 3rd Division of the Second Corps, Hancock turned the division command over to his old friend, while George Willard, Colonel of the 125th New York took over the command of Hays’ former brigade.22

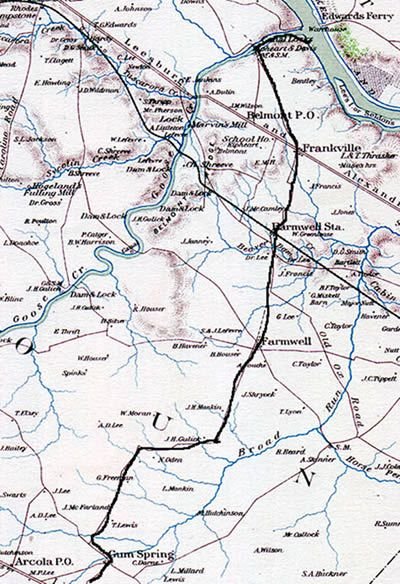

The march of the Second Corps on June 24-26, 1863.

(O.R. Atlas Plate 7 no.1)

The route of the 108th New York, as well as the rest of the Corps, from Gum Springs to Edwards Ferry is not clearly documented. Most accounts simply state that they moved to Edwards Ferry and offer no further detail.23 Since the area around Gum Springs was fairly open and reasonably flat, the troops could possibly have moved overland to the ferry crossing which was approximately 12 miles to the northeast. But it had rained all day of the 25th until well after midnight and into the morning of the 26th. Given the probable condition of the fields after the rain, the infantry may have been fine slogging through mud but the artillery and wagon train would need some sort of established thoroughfare. Gum Springs in 1863 had three possible routes to the Ferry. A tributary from the Potomac, Broad Run, ran mostly southwest from the river and passed through Gum Springs. Two roads, one on each side of Broad Run, ran from Gum Springs to the northeast.

The first road was located southeast of Broad Run where it intersected the Gum Springs Road, east of the town. This road led northeast to Guildford Station on the Loudoun-Hampshire Railroad. From Guildford Station, the Second Corps would have had to negotiate a number of roads to reach the Leesburg-Alexandria Turnpike which would have taken them northwest to Goose Creek then east to Edwards Ferry. The second road was northwest of Broad Run, intersected the Gum Springs Road northwest of the town, and ran northeast to Farnwell Station on the Loudoun-Hampshire line, about 4 to 5 miles northwest of Guildford Stn. A road ran directly northeast out of Farmwell Station to Frankville, approximately two miles from Goose Creek, on the Leesburg-Alexandria Turnpike. A third possible route was to take the Gum Springs Road which ran northwest out of the town and became the Old Carolina Road, north of Goose Creek. Take this road to Goose Creek, then follow the Goose Creek Canal system to Edwards Ferry. Of the three possible choices, the Second Corps probably took the second route through Farmwell Station.

The first route through Guildford Station would have taken them too far to the east and would require a crossing of Broad Run at some point. The third route was out of their way at the start and to depend on the canal system would be too difficult for the guns and trains. Of the three, only the second route is the most direct. The men were becoming exhausted with the march so any route which saved time and distance would be preferable. The course of the Second Corps cannot be finally verified but there are three pieces of information that could turn possibility into probability. Sergeant Ben Hirst of the 14th Connecticut, in a letter to his wife, stated that “we resumed our march in the Direction of Leesburg” which would mean an initial movement to the northwest. However, he never mentioned a canal system so the move could have been northwest to Farmwell Station. Thomas Galwey of the 8th Ohio had guard of the wagon train when he left Gum Springs and he recalled the number of sloughs that the wagons had to deal with. The route to Farmwell Station crossed numerous creeks or marsh areas that would play havoc for the lumbering wagons24. Although the same could be claimed for the Guildford Station route, the initial direction would have had to been southwest. Finally, all the accounts imply a direct march to Edwards Ferry with no deviations. Crossing Broad Run, after two days of rain, as well as a retrograde march would have been mentioned. The same logic applies to the unsuitability of the Goose Creek Canal system. Ultimately, the Second Corps arrived at Edwards Ferry on the night of June 26th, around 9 p.m. The 108th New York thought that the day’s march was over and had camped. They were soon disillusioned when the order arrived “to strike tents” and they were hurried across “the Potomac on a pontoon bridge 1300 feet long and 65 pontoons.” Andrew Boyd noted in his diary, “we have left old Virginia in our rear and are in the beautiful state of Maryland; it is small but the land is nice; would like to live here.”25

On June 26, 1863, as the Second Corps plodded toward Edward’s Ferry and approximately 80 miles to the north, the citizens of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania had their first experience with the Army of Northern Virginia when Gordon’s Brigade of Early’s Division from Ewell’s Second Corps arrived in town about four o’clock in the afternoon.26 The cry that the “Rebels are Coming” started in early June but as “day by day passed and they did not come, we lost faith in their coming and it grew to be an old story.” Eventually the inhabitants of Gettysburg “tried to make ourselves believe they would never come.”27 If the white folk of Gettysburg were skeptical about the arrival of the Rebels, the black people of the community took the threat seriously. Sallie Myers recorded in her diary:

Gettysburg is only about 7 miles from Mason & Dixon’s Line, and we have a population of between 300 & 400 colored people. Their fear of the rebels was caused by the belief that they would br captured and sold as slaves if the Rebels came north into the States. I know not how much cause they had for their fears, but it was a terrible reality to them. All who could got away...28

However, as the Rebel invasion became a reality, the exodus spread to the white population. David Buehler, the town postmaster and a Black Republican, took flight from his house on Baltimore Street (now number 112). His wife Fannie watched his escape as he turned right into East Middle Street, and recalled that after “he had turned the corner at Middle street, knowing he must escape with all possible haste, he hailed the driver of an empty wagon, who was also trying to get away in order to save his horse.” Mr. Buehler “jumped in the wagon and the man droveas fast as possible toward York street and reached the corner of York and Stratton streets at St. James church a little in advance of the Rebel cavalry, who were dashing down the street from the Diamond [Town Square].29 Gordon’s veterans and White’s cavalry battalion easily brushed aside the hastily cobbled together Federal protective force which consisted of Colonel William Jennings’ 26th Pennsylvania Emergency Infantry, the 40 members of the Philadelphia City Troop and the company of Independent Cavalry under Captain Robert Bell. Around 2 p.m. the remnants of Bell’s force and some of the Philadelphia City Troop “ spurred their horses into a full gallop and scattered out of town along roads to the south and east.” “Gettysburg was left to face its nightmare alone and defenseless”30and although the nightmare escalated five days later, for now, the townsfolk had to deal with the ever irascible Jubal Anderson Early, division commander in Ewell’s Second Corps, Army of Northern Virginia and regarded affectionately by Lee as his “bad old man.”31

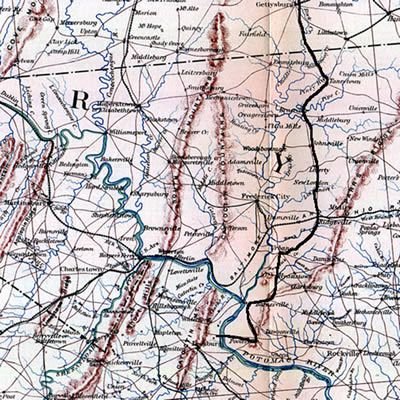

March of the Second Corps to Gettysburg, June 26 –July2, 1863.

(O.R.Atlas Plate 136).

While Early and Gordon attempted to extort goods and cash from the burghers of Gettysburg, the Second Corps finished crossing the Potomac in the early morning hours of Saturday, June 27th .32 The corps rested most of the 27th and did not break camp until 2 or 3 p.m. From Edwards Ferry, the troops moved northward on the road to Poolesville, then continued to Barnesville. On Sunday the 28th, they reached Monocacy Junction, near Frederick and were informed “that the command of the Army of the Potomac, that football of political intrigue and popular clamor, had undergone another change.”33 ‘Fightin’ Joe Hooker had been replaced by Major-General George Gordon Meade, the commander of the Fifth Corps.

The 108th New York had little time to ponder the significance of the change since the regiment was detached from the division and sent three miles west to Buckeyestown. Typically, the men from Rochester had just set up camp, cooked supper and were looking forward to their rest when they “were ordered to strike tents” and marched westward “ to hold a road.” Stuart’s cavalry was rumored to be in the area so the New Yorkers were part of the “arrangements for guarding the approaches to Frederick against any possible dash of cavalry.”34 On the evening of the 28th, Jeb Stuart and his cavalry were approximately 20 miles southeast of Buckeyestown at the town of Brookeville where he was paroling some of the Federal prisoners taken in his wagon train raid earlier in the day at Rockville. Dashing into Frederick through Hancock’s Second Corps and into the middle of the Army of the Potomac, while a worthy Stuartesque caper, was not on the mind of Lee’s colorful cavalryman. He was wrestling with the more mundane problem of how to swiftly re-join Lee while encumbered by more “than one hundred and twenty five best United States model wagons and splendid teams.”35 Consequently, the night of advanced guard duty for the 108th New York at Buckeyestown proved to be uneventful but the next day would not.

On June 29, 1863, the Second Corps marched at least 32 miles from Monocacy Junction to Uniontown, just south of Taneytown and about 18 miles from Gettysburg. Since the 108th was detached west of the main body, these men had to march three or four extra miles just to catch up in the morning. When the Rochester regiment finally did catch up, they found that their brigade had been assigned to guard the wagon train and the difficulty of the march increased since “the men were compelled to march most of the day parallel and in the same road as the wagons which crowded their march - it rendered this march peculiarly distressing.”36 The brigade was badly broken up by the train and the number of stragglers increased. Earlier in the day, the men had forded creeks but were not allowed to remove their shoes or roll up their trousers “on account of the delay it might occasion.” Sandy dust adhering to the wet pants “soon found its way into the worn shoes” and, as the march grew longer, caused “many of them to become foot-sore.”37 Yet still the march continued.

After the war, the regimental historian of the 108th remembered the march of June 29th as a race, based on an alleged $500 bet, between General Hancock and General Sykes, commander of the Fifth Corps, that “the old Second could outmarch the Fifth Corps” At one point, the story continued, the Fifth Corps passed the Second “and as the 140th [the other Rochester Regiment] was in that corps when they passed the 108th , there was a spirited fusillade of words exchanged.” The men of the 108th took the ribbing and sprang back into the march. Half an hour later, they passed the Fifth Corps in camp, “continued on several mile” and proved “clubs [the Second Corps’ insignia badge] were trumps in this game.”38 This story of the friendly race between the corps, related by the regimental historian of the 108th, who was permanently detached from the regiment after Chancellorsville and thus did not take part in the march, stemmed more from fiction than fact. Both corps started from south of Frederick, but with the Second Corps in the lead, the Fifth Corps took the road north through Frederick whereas the Second Corps missed the town by moving to the right on the road to Liberty then Johnsville and camped at Uniontown.39 At Liberty, Maryland, the two corps may have come into contact since that place had been the destination set out for the Fifth Corps but neither Corps’ historian mentioned such an occurrence nor do the other relevant regimental histories. Secondly, the existence of a bet between Hancock and Sykes was another imaginative creation. Neither Hancock nor any of his contemporary or modern biographers record such an extravagance and it is highly unlikely that Hancock, as a husband and father of two young children, would stake over two months pay on such a ludicrous wager.40 Nevertheless, every story contains a kernel of truth and in this case the motive for the length and duration of the march had more to do with Hancock’s ego than with his supposed sporting nature.

When George Meade took over the army on June 28,1863, he immediately issued marching orders for the various corps. The Second Corps was to march at 4.00 a.m. on the 29th to Frizzelberg which was a few miles southeast of Taneytown, near Pipe Creek. Meade at this point was still uncertain as to the exact whereabouts of Lee’s army and, perhaps, was starting to formulate the Pipe Creek defensive position in his mind. But the Second Corps did not start the march on time, in fact, was three hours late. An extremely embarrassed Hancock had to explain to Meade that the “delay of three hours is caused by the order having been left with an irresponsible person at these headquarters, a clerk who failed to deliver it.” In his reply the commanding general conveyed his “regrets” about the “delay” and suggested that the guilty messenger should be punished. Hancock assured the general that the “man in question” had been dealt with and repeated his apology for the “delay” which he intended to make up “by short cuts and rapid marching.”41 Hancock not only failed to expedite the first order of the new commander and fellow Pennsylvanian, he also held up the march of the Fifth Corps, Meade’s old command, that followed behind on the same road. SurelyHancock the Superb was mortified by this turn of events and- to put it mildly- in an ‘excited’ frame of mind which usually precipitated a titanic outburst of profanity. As promised, he “drove his men relentlessly through the heat, at least 32 miles and until 10.00 that evening where they finally made camp at Uniontown about two miles short of their original objective.”42 The march of June 29th was hardly a friendly competitive race, as the historian of the 108th recorded but rather a brutal exhausting “remarkable march of thirty two miles, moving upon a single road with artillery and trains.”43

On June 30th, the Second Corps rested and was mustered to receive pay. Hancock had regained his composure and, perhaps with a pang of guilt but certainly with a sense of relief, he issued a complimentary order to his soldiers “on their endurance of the march” that had helped him save his professional face44. After being paid, the men spent the remainder of the day in a restful manner. The next morning, July 1, an order arrived at daylight for the Corps to move to Taneytown but once more the order was almost lost due to mishap a at Second Corps Headquarters. Lt. Col. Charles H. Morgan, Hancock’s Inspector General and Chief of Staff wondered superstitiously if some

fatality seemed to attend our dispatches at this important juncture. This one was written on the common tissue paper, and was accompanied by another demanding the exercise of the greatest caution by corps commanders to prevent loss of dispatches. After reading the order of march, I stepped into the Quartermasters office to give some instructions concerning the train, and when I returned to my tent after a few minutes absence, the dispatch had vanished.

Morgan, with the image and audible echo of his boss’ embarrassment still vivid in his mind, calmly questioned his servant and noticed the remnants of the errant order stuck on the sole of the black man’s boot. The original was a shredded mess so Morgan, to avoid a further scene, verbally transmitted the order to Hancock then rode off to Taneytown to obtain “a copy of the dispatch.”45

At about 7 a.m., the 108th New York and the rest of the Union Second Corps marched to Taneytown while John Buford’s dismounted cavalry began to thwart the advance of Henry Heth’s Division from A.P.Hill’s Second Corps. along the Chambersburg Pike to Gettysburg, approximately 18 miles to the north. By noon the situation became serious. The First Corps had been mauled and Reynolds, its commander, was dead. Meade needed to send someone to take charge. Hancock was ordered to take command at Gettysburg. Into the afternoon the troops waited in anticipation and finally the Second Corps marched to Gettysburg under the command of Brig. Gen. John Gibbon. Dr.Wafer wrote that the morning march to Taneytown was “leisurely” but the order to Gettysburg “was promptly obeyed and with scarcely a halt, the corps crossed the state line into Pennsylvania” where they started to encounter the wreckage of the First Corps. With Little Round Top in view, roughly two miles to the north on the Taneytown Road, Hancock ordered the troops to halt “and take up a position across the road.”46 The next morning, they would move to Gettysburg.

When the 108th arrived in Gettysburg during the morning hours of July 2nd, 1863, the Rochester Regiment deployed as the extreme right of the Second Corps’ position on Cemetery Ridge. Hays’ division occupied the approximate area from Ziegler’s Grove to south of the Bryan buildings and just north of the Angle. The reserves were held in the adjacent fields to the east. Smyth’s brigade formed the front line in Ziegler’s Grove along Cemetery Ridge to south of the Bryan House. From right to left the regiments were the 108th New York, the 12th New Jersey, the 1St Delaware and the 14th Connecticut.47 The 108th was to support Lt. George A. Woodruff’s 1st United States, Battery ‘I’, composed of six 12 pound Napoleons, which was in an advanced and exposed position on the northern end of the ridge. Hays, perhaps still giddy from his recent promotion to division command, insisted “that the New Yorkers be positioned behind the line of guns and in front of the line of limbers” which would also expose the infantry “to Rebel counter battery fire.”48 Evidently Woodruff was not pleased by the presence of the 108th since he felt quite capable of defending his front and did not wish to have the performance of his men interfered with by the infantrymen.49. As the 108th took its position behind the Union battery, the action on the skirmish line to their front and left along the Emmitsburg Road was heating up dramatically. For Hays’ Division, the skirmishing began to focus on the Bliss farm and buildings which provided the Confederate riflemen ideal cover to ply their long range expertise on Union targets, preferably officers. The struggle around the Bliss farm continued on and off all day and each time Hays raised the ante with more men.50 On July 2nd, the 108th was forced to remain a spectator even though the skirmishing "was now general along the whole front" of the Rochester regiment, "especially in the town, - where the enemy had good cover."51 At 2 p.m., the artillery of Hill’s Third Corps opened on Smyth’s Brigade "with a severe fire of artillery, accompanied by an advance of infantry which drove in" the brigade skirmishers, the 39th New York (Garibaldi Guards).52 The Bliss barn was taken by the rebels, only to be lost and then taken again before nightfall.

The major Confederate offensive of July 2nd got under way shortly after 4 p.m. when Longstreet’s Corps waded into the exposed salient created on the Union left by Daniel Sickles’ Third Corps. Dr. Wafer of the 108th noticed that the attack started on the left but was moving north along the Union line since "one of their batteries directed its fire against our centre although its position was on their right". The New Yorkers were not bothered by this fire as the shells flew overhead and "were falling further to the right." Earlier in the afternoon before Longstreet’s attack, Woodruff’s Battery had been almost nonchalantly throwing"an occasional shell into the woods beyond as any movement of troops was discovered." When the ‘ball’ truly opened, after 4 p.m.and the Confederate artillery “had opened all along the line more or less, Woodruff’s battery replied spitefully [emphasis in original] to those batteries in our front and of course our regiment came in for its full share of shot and shell aimed at Woodruff’s guns.53 With the approach of sunset and early evening, Longstreet’s attack relentlessly continued northwards along the Emmitsburg Road, crushing unit after unit of Sickles’ Third Corps. Just after 6 p.m54., Major General Richard H. Anderson’s division of Hill’s Third Corps joined the Confederate wave when the brigades of David Lang (Perry’s brigade), Cadmus Marcellus Wilcox, Ambrose Ransom Wright and Carnot Posey moved directly against the depleted forces on Cemetery Ridge. As Anderson’s assault approached his position on the ridge, General Hancock quickly cobbled together a defense. The First Minnesota was sacrificed to stem the advance of Wilcox’s Brigade while Hays’ old New York brigade, now commanded by George L.Willard, joined the fight against Wilcox and also took on Barksdale’s Brigade which was farther south of the ridge.

Hays’ division was primarily engaged with the Mississippi Brigade of Carnot Posey who deployed the 48th and 19th Mississippi “as skirmishers” about “some 200 or 300 yards beyond the [Bliss] barn and house, on the spur of Cemetery Ridge west of the Emmitsburg Road.”55 Consequently as the artillery interchange between Pegram and Woodruff escalated so did the sharpshooter fire from Posey’s Mississipians at the Union battery. Since Powers was absent sick, Lt. Col. Pierce was in command of the regiment and he ordered the men to the prone position "in rear of the battery to avoid the fire as much as possible." Dr. Wafer, who made a habit of being on or close to the line of battle, recalled that "a shell with its fuze burning passed between the heads of myself and Col. Pierce - the burning fuze slightly singeing my left -whisker as it passed” and leaving the distinct odor of burnt hair. As Wafer lay on the shaking ground, fascinated by the awesome display of pyrotechnics, shell explosions heated his face and ricochets kicked up gravel onto his back. Woodruff’s gunners reminded him of the Titans in Greek mythology but, unlike their mythic counterparts, these red-legged ‘Titans’ could die. One he “saw whose face was partially swept away by a shell” still “clung to his gun for a few moments uttering unearthly screams” and “when he could no longer support himself through weakness fell and expired. Behind the guns, in the ranks of the regiment, men were being hit. Cpl. Seth Wells of Co.C "was rolling on the ground in agony - a piece of shell having struck him in the hip." Lieutenant A.D. John McDonald of Company C, another Kingston native, jumped to his feet when a sharpshooter’s bullet tore into his right shoulder, shattering the joint. Sergeant Box of Co.G was hit in the neck and spine and fellow Sergeant Henry Bufton, also a Canadian, hopped to the rear after a piece of shell entered his left foot. Yet, despite all the furor on July 2, the 108th New York had only one combat fatality. Dr. Francis Wafer described the episode:

Lieut. Evans rolled over in the agonies of death, shot in the brain. Myself and orderly Charles Dickson now had to get to our feet and one of the men assisting we removed the wounded man a few yards in the rear where by stooping low behind a low heap of field boulders there was some shelter from the storm. Here I examined his wounds and found the bullet had struck just in front of the ear and passed out behind, tearing up one of the most vital points of the brain. He expired on my knee in about twenty minutes.

The death of the twenty-nine-year-old Robert Evans had greater significance for Wafer since Evans was also a Canadian, from Toronto , killed far from home.56

The only success in Anderson’s attack was claimed by Ambrose Wright who reported that he temporarily broke the Union line in the area of the Copse of Trees. But Wright’s ‘success’ is viewed with skepticism and the general’s report has often been treated as fiction not fact. Nevertheless, Longstreet’s first assault, “the best three hours’ fighting ever done by any troops on ant battlefield”, was over and the Union line on Cemetery Ridge, while ragged, was still in tact.57 At sunset, a relative calm settled on the western slope of Cemetery Ridge and the fields around the Emmitsburg Road. The silence was short lived and broken when Ewell attacked East Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill. This fierce struggle in the growing darkness added to the day’s butcher’s bill but once more the Union line held. As the battleground faded into the night, “about 10 o’clock - all firing ceasing - the rattle of firearms was succeeded by sounds not so exciting but more melancholy, the familiar creaking of ambulances collecting the wounded for which the night was favorable, a beautiful moonlight one.” Wearily, Wafer pointed out the wounded to be removed to Lt. Sullivan of the 7th West Virginia, in charge of the division ambulance train. The doctor longed for a hot cup of coffee but no fires were permitted. Fortunately, Lt. Col. Pierce’s man servant brought coffee from the rear area and Pierce shared it with the grateful doctor.

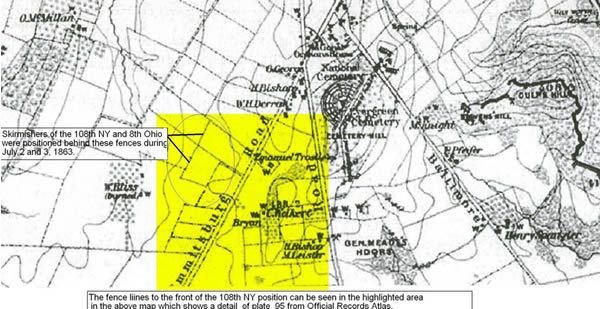

On the open plain before them, the mist from the previous night clung closely to the ground and gave promise of another hot humid day. The wispy, ghost-like vapor would slowly disappear with the sunrise. Sleep had been elusive for the men of the 108th. The intermittent skirmish fire had continued all night and kept the men in a state of constant vigilance. In his diary, Lieutenant Theron E. Parsons simply wrote that "our sleep was brief throughout the night."58 At about 4 a.m. on July 3, the fighting started again but this time behind the 108th in the area of Culp’s Hill as the 12th Corps fought to re-take the earthworks from Johnson’s Confederates. While the struggle for Culp’s Hill continued on the extreme right of the Federal line, the contest for the Bliss Farm started once more on Hays’ front. Companies A and C of the 108th New York were deployed as skirmishers west of the Emmitsburg Road, in the area of the present day Johns Street, opposite the park entrance. The two companies moved down from Ziegler’s Grove and "kept close to a fence that runs toward an old house on the Emmetsburg (sic) road."59 The ‘old house’ was the one usually labeled the "Emmanuel Trostle" house, even though no one is certain who lived there at the time of the battle.60 It is unlikely that they used the Bryan Farm lane since this conduit would bring them out too far to the left of their regimental front. Although the "Trostle" house was a bit to their right following the fence would bring the skirmishers out on the Emmitsburg Road almost in line with the regiment’s assigned position.

A and C crossed the road and deployed. With the 8th Ohio’s skirmishers on their left, the New Yorkers were soon involved in the firefight with the rebels ensconced in the Bliss barn. They also came under fire from Confederate marksmen behind a rail fence which ran northeast, almost parallel to and about 300 yards west of the Emmitsburg Road. Since the ground "was entirely desolate of anything in the way of protection,"61 the skirmishers of the 108th had to lay "down to load and raise up" to fire. Private John Rincker of Co. ‘A’ loaded a round and rose to return fire at the Bliss Barn. A rebel bullet hit him, passed clear through his body and spun him around like a dervish. As he lay on the ground, he pleaded for someone to take him from the field but was refused by Lt. Dwight H. Ostrander who "told him he could not spare any men just then." Rincker died later that night. Confederate fire from the fence line became so intolerable that the two companies of the 108th New York and a large contingent of the 8th Ohio, led by its Colonel, Franklin Sawyer, charged and "drove the rebels from the fence" back towards Long Lane. Thus the New Yorkers held the northern part of the fence for protection, while the 8th Ohio retained control of the southern section.62

108th NY at Gettysburg

For almost seven hours, the skirmish companies of the 108th and their Confederate counterparts exchanged rifle fire and the New Yorkers were blackened by powder and smoke. Mouths were dry and sticky with saltpeter residue. Their tongues, caked with gun powder, felt swollen and the intake of warm humid air only added to the discomfort. As the sun rose higher, there was no shade, no relief from the heat. Canteens were rapidly emptied and then, to make matters worse, they ran short of ammunition. Orders swiftly followed "to use the cartridges from the dead and wounded" but this, in turn, proved to be a short term solution. Lt. Ostrander ordered Cpl. William H. Raymond, appointed Acting Orderly Sergeant a few moments before, "to make a detail and send for a fresh supply" of ammunition.63 Raymond was a likeable nineteen-year-old, born in Penfield, N.Y. on May 30,1844. His light complexion had been burned to a brawny tan and the sun had bleached his brown hair, all of which only emphasized the blueness of his eyes. However, it was not his Nordic appearance but rather his physique that made him the object of teasing within the regiment. William was 6' 3" and "was so lean and lanky, that it was observed that he was altogether too thin to even cast a shadow or offer sufficient surface for a decent target."64 Cpl. Raymond decided not to appoint a detail, so he asked for volunteers. Not surprisingly, no one leapt at the opportunity. The gangly youth then volunteered himself and started back towards the regiment in Ziegler’s Grove. Before him for a distance of over 300 yards, there was nothing in the way of substantial cover. Luckily the land sloped slightly downward to the Emmitsburg Road but unfortunately sloped upwards to Ziegler’s Grove, his destination and safety. As he ran the gauntlet of fire, the slender target felt a few tugs or pulls on his clothing but managed to arrive unharmed at the regiment where his request for ammunition was quickly filled. The Lt. Colonel was concerned for the lad and thought that the skinny Corporal should play it safe and let someone else deliver the supply. Raymond recalled:

I said it might as well be myself as anyone else. The chances were talked over rapidly, and appeared poor enough. Nearly every officer present with the regiment and many of the men bade me good-bye, the opinion being freely expressed that I could not get back to the skirmish line alive.65

The young Corporal not only delivered 1000 rounds to his men, but had seven bullet holes in his clothing to verify his journey.

After the Culp’s Hill fight ended in the late morning, an unearthly silence “which spread over the battlefield after 11:00 A.M. deepened and created the illusion that the world of struggling armies had retired to sleep off its differences."66 The skirmish line was relieved at about 11 a.m. so both companies returned to Ziegler’s Grove then settled down with the rest of the regiment to wait in the growing silence and the drowsy heat of mid-day. The hum of insects and the occasional call of a cardinal broke "the ominous deathlike silence." In the heat of the sun, the blue wool uniforms, soaked with sweat, created a distorting convection-like aura around the men. Across the plain, shimmering figures could be vaguely discerned as they pushed guns into battery in the fields west of the Emmitsburg Road, opposite the Codori Farm. A member of the 1st Delaware recalled that the silence which "fell athwart both armies" was perceived as a "much dreaded, never to be forgotten, harbinger of death and destruction."67 The Federal troops knew that Lee would not settle for a stalemate and that there would be at least one more effort to destroy Meade’s army.

Shortly after 1:00 p.m. on July 3, two guns of the Washington Artillery of the Army of Northern Virginia "fired in quick succession" as a signal to begin the final act of the Gettysburg drama.68 After the signal, 161-164 guns 69of Lee’s army initiated the cannonade. Woodruff’s battery and hence the 108th New York in support once more became the target for Pegram’s Rebel guns on the northern end of Seminary Ridge.70 First Sergeant Andrew Boyd recalled initially “a cross fire” from the Confederate guns so the New Yorkers must have received some fire from the Oak Ridge area to the northwest or, less likely, overshoots from Benner’s Hill to the northeast.71 The fury of the Confederate guns escalated yet John Saunders, a sixteen-year-old in Co.F, still felt the need to raise himself and make the prosaic observation "this is pretty rough". Joe Deverall, captain of Co.K told the youth to "lie down and not be exposing himself." At this point, a shell exploded near Company A and took the foot off Bernard Matthews but Frank Deicenroth, who was nearby, was not so fortunate. The force of the exploding shell rolled Deicenroth over like a rag doll and tore away part of his side. He died instantly. Peter Anger, the sergeant who swam the canal at Fredericksburg with a Newfoundland dog, watched as a shell burst in the top of a tall oak tree. As the branches descended around him, his left forearm was stuck by a piece of shell and paralyzed. A fellow member of Company F reported the sergeant’s injuries to Lt. Col. Pierce who asked Anger if he “was dangerously hurt” to which the sergeant replied ‘no’. Since there was no blood the Lt. Colonel advised Anger that “you had better stay where you are, as you are just as safe as you would be going to the rear.” The sergeant agreed and “remained under fire till after the charge” but he was forced to cut open his coat sleeve to accommodate the swollen arm. As the rebel batteries on the opposite ridge continued to concentrate on Woodruff, the large oak trees of Ziegler’s Grove, which provided shade earlier, now became potentially lethal to the men of the 108th. Private Harris of Co. F remembered that large “limbs were torn from the trunks of the oak trees under which we lay and precipitated down on our heads. One shell came shrieking and tearing through the trees with the velocity of lightning, striking a caisson, causing it to explode, wounding several.” Jacob Spring Jr., a Swiss national, and three of his Company I mates claimed to have intimate knowledge of the event since they were lying “under a limber chest, when a rebel shell exploded the caisson right over their heads.” Of the four, Jacob Spring Jr. was the only survivor. Three or four men jumped up and attempted to vacate the area of the caisson but Lt. Dayton Card of Co.C arrested their flight and returned them to line.72 Lt. Card had just returned to his position when he "was struck by a piece of shell in the breast, tearing it open and carrying away a portion of his face." The young typesetter turned Lieutenant left a wife and four children in Rochester. Nearby, Lt. Carl Amiet of Company I moved towards the stricken brother officer, but was shot and died instantly before he could do anything. In late May, Carl had asked for leave to bury two of his young daughters and now his pregnant widowed wife, Amelia, would bury him in Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester.73

The fury continued unabated. In order to save time, some of Woodruff’s gunners stacked live shells “nearer the caissons and close behind the 108th.” A Rebel shot hit one of the stockpiles causing a tremendous deadly explosion near the New Yorkers but panic was prevented by the action of Captain David Shields, Hays’ Aide de Camp, who “restored confidence” to the frightened men.74 Black powder smoke thickened the air and removed sight but not sound as the continuous roar of the guns mixed with the screams of the wounded or the dying. Sultry heat and the lurid glow of the sun through the gun smoke bestowed an other worldly quality to the battle ground, like a painted scene of Hell by Hieronymus Bosch. Yet, incredibly, Jacob Winston experienced a vision of new life in the midst of this hellish nightmare. Winston and the other men from Company H hugged the earth behind Woodruff’s guns as Rebel artillery tore up the Union line, engulfing all in flame, smoke and destruction. As he lay there, he “experienced a feeling” that he would not “survive the engagement” and he knew that his refusal to become a Christian was the motive for God’s sentence. Since prospect of his death terrified him, Jacob’s fear increased proportionately with the intensity of the shelling until he finally cried to God for help or perhaps a remand. Eventually he struck a deal with the Almighty. In exchange for his life, Winston would serve the Lord by donning the cloth of a minister after the war. Suddenly calmer, Jacob attempted to communicate his conversion to a comrade, Robert Rider, who “rather abruptly” told him to lie down and protect his head. No sooner had Winston resumed the prone position and placed a metal canteen for protection in front of his face, when “a bullet crashed through” the canteen “ but was swerved from its course by the liquid and inflicted a two inch scalp wound” that “paralyzed” him. As young Winston was taken to the rear, did he wonder was this divine intervention, a warning not to betray the covenant or simply the common sense of Private Rider? 75

Directly to the front of the New Yorkers, Woodruff’s battery suffered severely. In the man made pandemonium, “horses were being torn and mangled in a terrible manner." Five horses attached to one caisson were down "and the other had his hind feet shot off at the ankles." The horse would attempt to stand "then drop down again." An artillery man crawled back towards the men of the 108th. When he reached Sergeant William Woodhull, he "asked me if I would ‘be so kind as to tie up his foot to stop the bleeding;’ it had been torn by a piece of shell." Woodhull bound the wound as best he could and the thankful gun crewman "crawled back to the rear". Shortly afterward, during the Confederate charge the helpful sergeant was “struck by a ball that went through my left chest, just above my heart, and came out through my back inside my shoulder blade.” Woodhull staggered, dropped his gun and “started back” towards safety and medical aid. However, his sense of humour was unaffected by the wound since he claimed that “a fellow who was protecting a large rock” helped him to the field hospital.76 Also on his way to the hospital was the Second Brigade commander, Col. Thomas Smyth. During his effort to “bring up some men who were straggling,” Smyth received a painful wound to the face from a piece of shell. Lt. Col. Pierce, now in command of the brigade after the wounding of Smyth,77 was struck with admiration not only for the gunners but also for the battery commander, Lt. George Woodruff. “While the shelling was the worst,” Woodruff casually strolled by where Pierce was standing. Calmly he remarked, “Pretty warm here isn’t it Col.?” and he did not mean the weather. Pierce replied “Mighty hot” and politely inquired, “can you silence those fellows?” Pausing for a moment, Woodruff then shook his head and replied "Ammunition all gone." 78 With his long range ammunition expended, Woodruff planned to remove the guns as targets but horses were so scarce, only 20 remaining out of 60, that the New Yorkers were ordered to assist his crews to pull the guns out of line by hand. The Lieutenant still had canister and, once the guns were relatively safe, he decided to wait for the inevitable infantry charge and then return the guns to the line. He did not have long to wait.

In McMillan’s Woods, fourteen hundred yards to the west of Ziegler’s Grove, the left wing of Longstreet’s column of assault, under Johnston Pettigrew, moved forward towards Hays’ Division on Cemetery Ridge. Further south, General George Pickett’s Division of the 1st Corps, the right wing of the assault, started forward towards its date with destiny at the Angle on Cemetery Ridge. To bolster the morale of his troops, General Hays rode up and down the Union line "exhorting ‘the boys’ to stand fast." Rebel artillery fire, as well as sharpshooter or skirmisher fire did not bother Hays as he specifically urged the 108th to protect the guns and not allow the rebels to touch the Napoleons. Soon Pettigrew’s line came into sight and Chauncey Harris remembered that the rebels advanced "in three lines of infantry from the woods and across the fields." He never saw troops march out with more military precision. Their lines were unbroken and the looked in the distance like statues. On they came, steady, firm, moving like so many automatons.79 Alexander Hays also remarked on the mechanical precision of the Confederate advance whereas a captain in the 126th New York appreciated the "beauty and grandeur of the scene" but found ambivalent expression in words from the Song of Solomon. Out loud, he repeated "Fair as the moon, bright as the sun and terrible as an army with banners."80 Hays had placed the 126th New York to the right of the 108th in Ziegler’s Grove and therefore the New Yorkers of Sherrill’s Brigade became the right flank of the 2nd Corps.81 As the 126th and the 108th moved into position along the western edge of Ziegler’s Grove, just north of the Bryan House, two old classmates from the University of Rochester spied each other. Lt. Col. Pierce and Captain Winfield Scott of the 126th "locked arms and walked” behind their regiments. Pierce said “Well Scott, we have sat beside each other in the classroom many a day; but this is a new experience. This isn’t much like digging out Greek roots." With "perfect composure and in confidence" the two friends formed their troops into line. “The 108th was taken out of the grove, drawn up in line of battle and then told to kneel down until the word ‘fire’.”82

The first line of the Confederate’s left wing was the division of Henry Heth, under the command of Pettigrew. At the start of the charge, the line was brigade front and from left to right was aligned as follows: Brockenbrough’s Brigade, commanded by Col. Robert M. Mayo; Davis’ Brigade; Pettigrew’s Brigade, commanded by Col. James K. Marshall; Archer’s Brigade, commanded by Col. Birkett Fry. Brockenbrough’s Brigade was the first to fall apart on the Confederate left. Captain Louis G. Young noticed that when the charge started Davis’ Brigade came out of McMillan’s Woods with a rush but not Brockenbrough’s Brigade. Young approached Pettigrew and asked if he should go and get the errant brigade. Pettigrew replied:

"No" that it might follow and if it failed to do so it would not matter. This brigade was a small brigade that had suffered from frequent change of commanders and had been so badly handled that it was in a chronic state of demoralization and was not to be relied upon; it was virtually of no value in a fight.83

Despite Young’s uncharitable claim, Brockenbrough’s Brigade did advance but in an awkward manner since the right half of the brigade moved forward but the left did not. Eventually, it got itself together but in the area of the Bliss Orchard, it came within range of the artillery on Cemetery Hill.84 Major Thomas Ward Osborn, Chief of the 11th Corps Artillery, was in charge of the guns positioned on Cemetery Hill. From his vantage point, he had the perfect view of the "left of the charging column" which "rested on a line perpendicular to our front then stretching away to the right beyond our view, thus offering an excellent front for our artillery fire." Osborn brought the whole force of his guns “to bear upon this column, and the havoc produced upon their ranks was truly surprising." Captain Fred Edgell, 1st New Hampshire Battery on Cemetery Hill, fired "obliquely" on "the left of the attacking columns with destructive effect as that wing was broken and fled across the field to the woods." A Union officer wrote:

The distinct graceful lines of the rebels underwent an instantaneous transformation. They were at once enveloped in a dense cloud of smoke and dust. Arms, heads, blankets, guns and knapsacks were thrown and tossed into the clear air. Their track, as they advanced, was strewn with dead and wounded. A moan went up from the field, distinctly to be heard amid the storm of battle...

What remained of the Confederate Left “still advanced amid the deafening roar of artillery and the 8th Ohio, which was still west of the Emmitsburg Road, added further discomfort to the Virginia brigade.85

Although Col. Sawyer had asked to have his men relieved, the majority of the 8th Ohio still occupied the southern part of the fence which they had taken earlier. When Brockenbrough’s Brigade initially advanced, the Ohio regiment used the fence as a parapet to fire directly into the Virginians. For a second time in the battle this Confederate brigade failed. As a result, the front line of Pettigrew’s assault column was reduced by one brigade and now Davis’s troops became the unsupported left. The Ohians, still northeast of the Bliss Farm, “changed front forward on the left company, thus presenting our front to the left flank of the advancing rebel column” and from behind an adjacent fence, which ran perpendicularly to the road , fired into the already shaken Rebels.86 The Union artillery fire as well as that of the 8th Ohio caused left started to drift towards the right and began to compact the entire line. Consequently, the exposed left flank of the Confederate assault column would just strike near the centre of Smyth’s Brigade and to the left of the 108th New York.

As the Confederate line approached within canister range, the Rochester “boys moved the battery forward again and Lieutenant Woodruff poured the canister into the ranks of the advancing rebels.” When the blow finally landed, the Rochester men faced elements of Davis’ as well as Lane’s Brigades on their left front. The brunt of the onslaught was borne by the regiments in the area of the Bryan House, just south of Ziegler’s Grove. Those of the 108th, not drafted as gun crews for Woodruff, fired obliquely to the left into the Rebel mass. They took return fire from the Confederate troops to their left and also from those who remained west of the Emmitsburg Road. Jerome Brownell of Company E was hit twice, “a slight flesh wound in the thigh and a bad wound in the right shoulder with a partial loss of clavical (sic) bone.” At this point, the Rebel first line seemed to break but quickly reformed with the second line into another assault despite the fury of fire from Smyth’s and Sherrill’s brigades and the double canister from Woodruff. The field disappeared into black choking smoke. Wounded wandered into the line of fire, confused, unable to tell front from rear. Timothy Keefe of Company K led his friend Bernard Matthews through the blackness to the rear. Matthews lost his right leg below the knee but would have bled to death without the help of his friend. Pvt. Harris remembered three separate charges and during each one Lt. Col. Pierce went "back and forth along the line encouraging the boys and cheering them up by his cool example." On ‘the third and last time they were repulsed” and the rout was accelerated by the devastating flank fire from Union forces formed along the post and rail fence which enclosed the Bryan Farm lane on the left of Pettigrew’s force.87 Adding to the destruction, Woodruff ordered "Lt. John Egan , commanding the left section, to train his guns to the left to enfilade Longstreet’s advancing column." Woodruff had just delivered the order and started to wheel his horse "to pass in rear" of the right section, when he "was struck" by a ball. He died the next day. Overall the rebel force in front of Hays "found itself within a vortex of fire; through which it was impossible to advance, and difficult to retreat."88 When the charge finally collapsed, elements of the 108th may have joined the flanking force since Pvt. Harris wrote to his father that many "of our troops rushed down into the field and hundreds of prisoners, many stands of colors and any quantity of arms were taken." Thomas White of Company F corroborates Harris since he recalled that the 108th held “position until we were ordered to charge and took many prisoners.” At this time, General Hays performed his extempore victory celebration. He grabbed a stand of captured colors and "carrying them back he rode at a gallop along the front of our lines, laughing and trailing the rebel flag in the dust."89 The battle of Gettysburg was essentially finished and the Union had hung on for its second ‘technical’ victory against Lee but, as always, the human cost had been enormous.

Moments before the charge dissipated, Lt. Col. Francis Pierce, caught up in “the glorious excitement of the fight”, realized he could never return to teaching in Rochester. This would be his life! The majesty “of the roar and booming of 150 cannons” or “the yell of the advancing enemy, the answering yell of difiance (sic) of the boys, the splintering of mighty oaks by artillery fire - all burned into his mind and imagination. The ineffable grandness of the scene terrified him and enraptured him. But once the euphoria subsided and after “the fight is over”,

then one realizes what had been going on. Then he sees the wounded, hears the groans, sees perhaps his own dearest friend, with whom he was talking only a moment before, lie before him a mangled mass of blood and flesh, scarcely recognizable, to view death and destruction in every shape brings one back to his senses again.

Pierce wandered, almost trance-like, along his portion of the ridge through the thinning black smoke, the rubble, the noise, the stifling heat, through the seventy odd dead horses near the scene of Woodruff’s wounding. Finally with the madness of battle subsiding, he moved with purpose in the direction of the field hospital and his wounded men. On the way, he met an ambulance that carried four men from his old Co. ‘F’. Daniel Schout, Darwin Skinner and John Swager, all bade him farewell and hoped to return. The fourth man, Enoch K. Miller, the diminutive Corporal of the Color Guard had been shot through the chest during the final few minutes of the fight with the bullet passing through the left lung and exiting his back. Miller attempting to speak to Pierce got out only “‘Good bye Col.’ then gurgled something in his throat.”90

Dr. Francis Wafer was also quite cognizant of the cost since he had been dealing with the human wreckage for the last two days. On July 3, Wafer spent part of the day with the regiment but as the wounded mounted he went back to the Peter Frey farmhouse, located approximately one-quarter mile south of Ziegler’s Grove on the Taneytown Road.. The farmhouse functioned as a crude type of triage where "some Surgeons who were on duty in the field assembled to apply light dressings to the wounds and superintend the removal of the wounded in ambulances to the operating hospital further in the rear." Once Wafer arrived at the Frey farmhouse, he "found more than enough to do for the remainder of the day." At one point, as the battle raged on the ridge, an orderly stormed into the field hospital “in search of a Surgeon for Genl. Hancock.” Wafer was preoccupied and did not hear the request. His assistant told him later that another surgeon refused to comply and Hancock’s orderly “went away threatening to report all those Surgeons present.” Wafer always regretted that he did not go to Hancock’s aid, not because of the verbal threat but rather he “ would have been glad to have an opportunity to render a service to the gallant leader of the 2nd Corps.”91

As the day wore on the doctor became aware of the total cost to the regiment. On June 30, the June report listed a total of 305 present, 31 officers and 274 enlisted men. However, the actual number of troops of the 108th who were present and ready for combat on July 2 was closer to 200 men.92 Over the two days that the regiment was engaged, the New Yorkers lost 16 killed and 86 wounded for a total of 102 or 51% loss for the total number involved. Fifty-four Union regiments suffered losses of fifty percent or more. None of the regiments positioned on Cemetery Ridge to the immediate left of the 108th suffered greater loss. It would appear that supporting a battery was more dangerous than previously supposed. To lay under fire for two days, with little or no protection and limited movement, while the battery to be supported drew Rebel artillery fire upon itself and the regiment is not the stuff of romance but is the reality of courage. In a letter to his friend in Penfield, James Moore, a private in Co. ‘A’ of the 108th New York and wounded in the ankle on July 3rd, attempted to put into words the experience of the Rochester men at Gettysburg:

God has given us the victory... but it is a dear victory if human life be taken into account, the loss in killed and wounded is frightful on both sides, the 108th is only a name now, the regiment is gone, we had to support Rickett’s regular Battery close up to the guns and shell and shot did its work, for the 108th numbers about 50 men for duty.93

Just over10 months earlier, the 108th New York, nearly a 1000 strong, had proudly marched through the streets of Rochester on the way to war.

Endnotes

1 108th New York, p.191.

2 Wafer-Diary, pp.21-25.

3 Ibid., pp.25-28.

4108th New York, p.45.

5 Hirst,The Boys from Rockville, p.130.

6 James I. Robertson, Jr., Stonewall Jackson: The Man, The Soldier, The Legend, (New York: MacMillan Publishing USA, 1997), pp. 751, 754.

7 William P. Seville, History of the First Regiment,Delaware Volunteers, rpt. Longstreet House (Hightstown, N.J: Longstreet House, 1986), p.77.Hereafter cited as 1st Delaware.

8 O.R.,27, 3, pp.68-69, 299; Second Corps, p.254-56; Ezra J. Walker, Generals in Blue(Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press,1999), p.95-96 Hereafter cited as Generals in Blue ; Josiah Marshall Favill, The Diary of a Young Officer (Chicago: R.R. Donnelley & Sons Company, 1909) rpt. Butternut and Blue (Baltimore: Butternut and Blue, 2000),p 236. Favill’s diary entry for May 12, 1863, indicates that Hancock may have been unofficially in command a little over a month before his official appointment. Couch went to Washington after the battle to lobby for Hooker’s removal or his own relief so the degree of active control he exerted over the Corps until his official transfer in June is hard to determine. Hereafter cited as Favill-Diary.

9 108th New York, p.123;14th Connecticut, p.130. To follow the itinerary of the march of the Second Corps to Gettysburg see O.R. Atlas, plates 7,8, 27,116,136 ; 108th New York, p.298(Peck episode).

10 Wafer-Diary, pp.33-35.

11 Wafer-Diary, p.39 ; 108th New York, p.47 ; Longacre, To Gettysburg and Beyond, p.112.

12 108th New York, pp.47,123.

13 Ibid.,p.124.

14John Gibbon, Personal Recollections of the Civil War (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons,1928), rpt. Morningside (Dayton, Ohio:Press of Morningside Bookshop,1988), pp.125-26 ; Francis Walker, p.259 ; O.R.,27,III, p.247.

15 15.O.R. 27,III, pp.274,291,444.

16 Favill-Diary, pp.238,246-48.

17 O.R. 27,III, pp.309,318.

18 O.R.27,II, p.692 ; John Gibbon, p.128; Walker, Second Corps,p.259 ; Favill-Diary, pp. 238-39.

19 O.R. 27,III, p.318 ; Favill-Diary, p.239.

20 Wafer-Diary, p.40 ; The Boys of Rockville, p. 142.

21 Favill-Diary, p.239 ; 108th New York, p.124.

22 David M.Jordan, Winfield Scott Hancock, A Soldier’s Life ( Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988), p.77 ; Generals in Blue, p.223 ; Second Corps, p.260.

23 108th New York, p.124 ; Second Corps, p.261 ; Favill-Diary, p.240 ;Page, 14th Connecticut, p.133 ; John Gibbon, p.128 ; 1st Delaware, p.79 ; Ernest L. Waitt, compiler, History of the Nineteenth Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry 1861-1865 (Salem, Mass.: The Salem Press, 1906) rpt.Butternut and Blue (Baltimore: Butternut and Blue,1988), p.216 ; George A. Bruce, The Twentieth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry 1861-1865, p.264 ; Thomas Aldrich, The History of Battery A First Regiment Rhode Island Light Artillery (Providence : Snow & Farnham, 1904) rpt. Higginson Book Company ( Salem, Mass.: Higginson Book Company, 1998), p.189 ;John Rhodes,The History of Battery B First Regiment Rhode Island Light Artillery (Providence: Snow & Farnham, 1894) rpt. Butternut and Blue (Balitmore: Butternut and Blue, 1997),p.195 ; John Day Smith, The History of the Nineteenth Regiment of Maine Volunteer Infantry( Minneapolis: The Great Western Printing Company, 1909) rpt. Ron R. Van Sickle Military Books (Gaithersburg, MD.:Ron R. Van Sickle Military Books, 1988), p.59.

24 The Boys From Rockville, p.142 ;Thomas Galwey, The Valiant Hours ( Harrisburg PA.:The Stackpole Company, 1961), p.95.

25 108th New York, p.124.

26 Sarah Sites Rodgers, The Ties of the Past, The Gettysburg Diaries of Salome Myers Stewart 1854-1922(Gettysburg,PA.:Thomas Publications,1996),p.161.

27 Fannie J. Buehler, Recollections of the Rebel Invasion and One Woman’s Experience During the Battle of Gettysburg (Gettysburg: State and Sentinel Print, 1900) rpt. Gary T. Hawbaker (Hershey, PA.: Gary T. Hawbaker, n.d.), p.6.

28 The Ties of the Past, p.160

29 Fannie J. Buehler, p.13 ; William Frassinito, Early Photography at Gettysburg (Gettysburg: Thomas Publications,1995),p.80.