Chapter Seven

Rochester's Forgotten Regiment:

The 108th New York In The Civil War

By Terence G. Crooks

Chapter Seven:

A Firm Determination

After the Mine Run Campaign, the Second Corps of the Army of the Potomac, like a dog circling his bed, eventually settled into camp around Stevensburg, Virginia, about 12 miles north of the Rapidan River. Most of Hays’ Division encamped south of the town but Smyth’s Brigade was thrust out “about four miles in advance of any other infantry” ostensibly to support the cavalry pickets at Morton’s Ford. This brigade was nearer to Lee’s army than any other, and, with “the exception of a feeble cavalry picket”, had nothing between it and the Rebels.1 Nevertheless, despite the rather “exposed position”, the men set to work on their camp which a Jersey man christened “Camp in the Mud”. By January, 1864, the men had created a comfortable camp, logged-wall cabins with tent roofs, company avenues and proper sanitation. For favorite officers, the boys turned out “en masse” to build log houses of “solid oak slabs fourteen inches wide and when completed” measured “eight feet by twelve and nearly six feet high at the eaves” with a floor of pine logs.2 Such dwellings helped alleviate the discomfort of the cold weather and, perhaps more importantly, created an enclave of sanity in the chaos – a reminder of a quieter time of housewarmings or evenings with family friends. But at the fragile edge of the enclave, like an uninvited guest, shimmered the spectre of the spring campaign and further bloodletting.

About 150 air miles southeast of Stevensburg on the northern tip of the James Peninsula stood Fort Monroe, the star-shaped fortress which guarded the entrance into Hampton Roads and the James River from Chesapeake Bay. In command, for the second time, was Major-General Benjamin Franklin Butler, remembered affectionately by the ladies of the South, particularly those from New Orleans, as “Beast” Butler or “Spoons” Butler.3 The diminutive political general from Lowell, Massachusetts, was not happy with his reassignment to Fort Monroe and viewed it as a deliberate attempt to shelve him in the hope that he might go away.4 But Ben had no intention of going gently into obscurity so on December 5, 1863, while the Army of the Potomac returned from Mine Run, Brigadier-General Edward Augustus Wild, under the auspices of Ben Butler, launched a Federal raid from Norfolk, Virginia south to South Camden Court-House in North Carolina. Wild suited his name. He was an ardent abolitionist in the John Brown mold with an abundance of hatred for southern slaveholders. After graduating from Harvard in 1844, Wild attended Jefferson Medical College, then continued his medical studies in Paris and eventually ended up in the Crimean War as a surgeon. With the advent of the Civil War, he served in the 1st Massachusetts and later led the 35th Massachusetts at South Mountain where he received a severe wound that cost him his left arm. Upon recovery, he received his general’s star and “assisted in recruiting the regiments of Negro troops known as ‘Wild’s African Brigade’, which he commanded until the close of the war.”5 The raid in December gave Wild and his men an opportunity to loot and burn secessionist property freely, all the while claiming the moral high ground as an army devoted to the protection of loyal Unionists. As the raid progressed, Wild’s force was constantly “pestered” by southern guerillas so, in an attempt to rid themselves of these pests, the Union troops tried ambushes, outright pursuit and torching the guerilla camps, all of which proved futile. However, Wild did manage to capture Daniel Bright, “a deserter from the Sixty Second Georgia Regiment” who was alleged to be “carrying on robbery and pillage in the peaceable counties of Camden and Pasquotank.” Bright was summarily tried as a guerilla and executed. Attached to his body was a placard, which read: “This guerilla hanged by order of Brigadier-General Wild.” To insure further tranquility, Wild also arrested, manacled and incarcerated Mrs.Phoebe Munden and Mrs. Elizabeth Weeks whose husbands served in the 68th North Carolina, a regiment “raised for the protection of the State” but identified by the overzealous Wild as a band of guerillas. Needless to add, the duo of Butler and Wild generated considerable southern outrage and controversy6.

John Forbes, Newton C. Jones and a number of other residents from South Mills, North Carolina made a gruesome discovery on the morning of January 13, 1864. At the end of a rope, tied to the crossbeam of the turnpike gate, swung the body of a black Federal soldier. Fear of reprisal from Butler and Wild initially motivated the citizens to implore “that you will not attach any blame to any of the citizens of this neighbourhood, as we were entirely ignorant of the circumstances until we found the body.” Pinned to this body was the following note:

Here hangs Private Samuel Jones, of Company B, Fifth Ohio Regiment, by order of Major General Pickett, in retaliation for Private Daniel Bright of Company L, Sixty-second Georgia Regiment (Colonel Griffin’s), hung December 18, 1863, by order of Brigadier General Wild.7

Throughout December, George Pickett, of Gettysburg fame and currently commander of the Department of North Carolina, fumed impotently at his headquarters in Petersburg while Wild’s African Brigade laid waste to Camden and Pasquotank counties. As an aristocratic Southerner, he was infuriated by Wild’s and Butler’s disregard for the rules of fair play and civilized warfare. Also, as a white Southern male, he was haunted by the image of “swarms of blacks” let loose “upon our ladies and defenseless families” – all the anger created by years of repression and servitude unleashed against their owners and the belles of the South, such as Lasalle Corbell Pickett, his young wife of four months. With futile fury, he wrote “it makes my blood boil to think of these enormities being practiced and we have no way of arresting them”. He went on to argue that “against such warfare there is but one resource – to hang every one captured belonging to the expedition and after ward any one caught who belongs to Butler’s department.” Consequently Samuel Jones, whose earthly remains swayed slowly in the morning air at South Mills was Pickett’s initial response to Beast Butler and his minion, Edward Wild.8

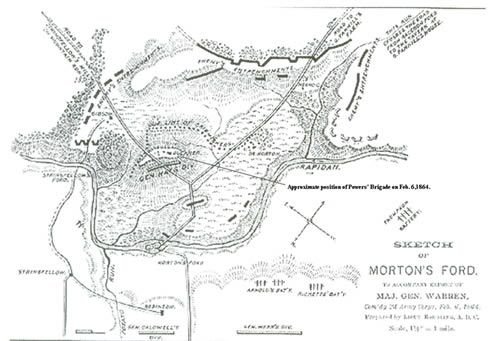

February 6-7, 1864. Sketch of Morton’s Ford to accompany

Report of Maj.Gen. Warren, Commanding Second Corps.

(Sketch prepared by Lieut. Roebling , A.D.C. Scale 1¼” = 1 mile , O.R. 33., p.117).

At first, Butler believed that Private Jones “was evidently taken from among the prisoners of war at Richmond and turned over to General Pickett” for a retaliatory execution. Later, it turned out that Jones was actually Samuel Jordan, Company D, Fifth U.S. Colored Troops “captured from that regiment on General Wild’s late expedition into North Carolina” and Pickett, true to his threat, had executed Jordan for his association with both Wild and Butler.9Typically, the matter degenerated into mutual name calling and accusations and was never resolved but the uproar over prisoners and executions did get Butler to cast his eye at the thousands of Federal prisoners in Richmond. At the end of December, when Butler received a ciphered message from Elizabeth Van Lew that the Union prisoners were soon to be sent to Georgia, he decided on a raid into Richmond “in an attempt to do our duty and rescue our friends.”10But in order to pursue his plan and his return to the limelight, the cock-eyed general from Massachusetts needed the Army of the Potomac, quietly encamped in Northern Virginia, and permission from the Union high command. Asking General in Chief Henry Halleck to make a decision was like pulling eyeteeth so, not surprisingly, Butler circumvented “Old Brains” and pitched his idea directly to Edwin Stanton, Lincoln’s Secretary of War. However, in a Catch 22 move, Stanton referred Butler to Halleck, who in turn dumped the doughty general’s request onto the lap of Meade’s temporary replacement as commander of the Army of the Potomac, Major General John Sedgwick, also a man more comfortable following orders than originating them. Butler believed that Lee had substantially weakened his army on the Rapidan in order to attack New Berne on February 1 – he had not – and therefore if the Army of the Potomac could mount a demonstration across the Rapidan, Lee would have to compensate by weakening his force at Richmond which, in turn, would leave Richmond ripe for the plucking, by none other than Benjamin Franklin Butler. Quite accurately a modern scholar labeled Butler’s plan as a “hare brained scheme.” From the outset, Sedgwick was skeptical if not downright reluctant. He doubted that a substantial part of Lee’s army had been sent south and went on to explain that the “Rapidan in my front is so strongly intrenched that a demonstration upon it would not disturb Lee’s army.” Nevertheless, with no clear leadership from above, Sedgwick finally acquiesced, even though he considered Butler’s plan as “childish.”11 The Second Corps would lead the demonstration at Morton’s Ford, while, at the same time, cavalry units threatened Barnett and Culpeper Fords and the First Corps demonstrated at Raccoon Ford. Supposedly, the diversion would last three days in order to give Butler time to capture the Confederate capital.12

On Saturday, Feb. 6, 1864, the Second Corps moved south towards Morton’s Ford. Rain that had threatened on the 5th began to fall, a cold drizzle, occasionally converted into stinging ice pellets by the gusting winds. Hays’ Third Division led the way when Carroll’s First Brigade and Owen’s Third Brigade left Stevensburg around 7.00 a.m. Since the Second Brigade was posted farther south of Stevensburg and closer to the ford, Colonel Charles Powers, temporarily in command of the brigade, formed the command “in line on the Morton’s Ford [road], 1 mile north of the ford” and “there awaited the arrival of the division.”13 When Powers called the brigade to fall in, Francis Wafer experienced a strange sensation as he watched the wives of the officers of the 108th New York stand by as their husbands departed, perhaps saying goodbye for the last time. The ladies had received a twenty day pass in January to visit their husbands and now Wafer tried to imagine their feelings and anguish as their men moved toward the battlefield. He felt fortunate that he had no wife and thus would never have to witness or be the cause of such emotional turmoil. Suddenly his reverie was broken with the arrival of the other brigades of the division, followed shortly by the other divisions of the corps. From the start, it was quite clear that Hays was in fine combative form and intended his Third Division to carry the weight of the demonstration. Warren, perhaps in one of his moods or actually feeling “very unwell in the morning”, seemed disinterested in the Butler charade and since the day was stormy and since the operation was to be only a “demonstration”, he graciously” allowed the movement to proceed under direction of General Caldwell”, who was hesitant to restrain the enthusiasm of the Third Division commander. Once at the ford, Hays was ordered “to test” the “position and strength” of the Rebel entrenchments, so he called on his old New York Brigade, now commanded by Brig.Gen. Joshua Owen. Owen selected a total of 300 veteran skirmishers, 100 men from each of the 39th ,125th and 126th New York Regiments and put them under the command of Captain R.S. Seabury “to effect a crossing and to skirmish with the enemy if he were so deposed.” Simply “to make a demonstration” against the Rebel position was the prime directive, “but not to press him too hard, as it was not desired to bring on an engagement.”14

The drama that unfolded over the next three days literally took place in an enormous, natural outdoor amphitheatre. Morton’s Ford on the Rapidan River was located on a shallow flood plain where the river supposedly reached a depth of only 4 feet. On the Rebel side, the southern bank was about 6 to 8 feet high and the ground gradually rose for about a mile to a ridge which enclosed the ford in a semicircle of high ground, joining “the bank of the river above and below.” Confederate works and entrenchments lined this wooded ridge and therefore had “complete command of the ground” where the Federal assault was to take place.15 But Lady Luck smiled on the Union demonstration, at least initially, she did. On that cold, gusty and drizzly first Saturday of February, 1864, the Union troops caught the Confederate forces in, what would later be called in hockey, an improper line change. No one on the Rebel side of the river expected any enemy activity in the dead of winter, so the brigade on duty at the river, anticipating the momentary arrival of Steuart’s relieving brigade, decided to leave early and to head back to their camp, thereby leaving the ford to be guarded by a handful of skirmishers and the First Company of the Richmond Howitzers whose four guns were deployed on the ridge to the east of Morton’s Ford Road. Their camp was located behind and below their artillery pieces in a wooded area on the back slope of the encircling ridge. At the time of the shift change, however, nearly all the Howitzers were in their camp since Ben Lambert, the hair style trendsetter of the First Company, had shaved his head to achieve what he termed “the ‘horse thief’ cut” and so all the members of the Howitzers who coveted the minimalist hairdo were engaged in tonsorial activities. Just as Sergeant Van McCreey, the resident barber and sole owner of the only pair of scissors in the company, was midway through the hair cut of Bob McIntosh, the inconsiderate Federals crossed the ford, forcing the barber to abandon his endeavors and Bob to enter the fray with half a hair cut, much to the delight of his battery mates.16 While barber towels flew and the Richmond Howitzers rushed to their posts, Captain Seabury and his selected skirmishers splashed across the ford, overran the “rifle pits and unfinished abatis” and quickly captured 30 Rebels. Unopposed, they advanced “for three quarters of a mile” to a small ridge, which ran, like a stage, in a northeasterly-southwesterly direction across the open end of the amphitheatre in “full view of the enemy’s camp and intrenchments”, 800 yards away. At each end of the ridge, stood the residences of Dr. Morton to the west and Major Buckner to the east. Owen immediately followed the skirmishers with the remainder of the Third Brigade, deploying his men on the right, near the Morton House. Fortunately for Hays’ Division, this ridge and the houses on it blocked the sightlines of the Richmond cannoneers and entirely concealed “the road from that point to the ford” so the Federal brigades could cross free from artillery fire. Compounding the problem, the morning fog and continuous drizzle did little to aid visibility for the Rebel gunners.17

While the Second and First Brigades of Hays’ Division stood ready to reinforce him, General Owen had to deal with stiffening Rebel resistance. At this point, the earlier luck began to turn against the Federals since there were now two Confederate brigades in the immediate vicinity where there should have been only one and this “gave double the usual force.” So, when the Union troops attempted to continue past the Morton house, they were held in place by the Richmond Howitzers who now had clear targets and by the men of the relieved and relieving brigades who began to fill up the Confederate works. In fact, Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell was on his way with most of the Second Corps from the Army of Northern Virginia. Owen, aware of the build up, noted that “the enemy advanced a stronger line of skirmishers, and began rapidly to concentrate his troops immediately in my front, and opened a vigorous fire both of infantry and artillery.” Shortly after noon, as things started to escalate geometrically, Owen telegraphed for help. At 1:15 p.m., Carroll’s First Brigade reported to Owen who placed it in reserve but, as the situation deteriorated, the brigade was soon needed to thwart a Rebel effort to turn the Union right flank. With every passing moment, increasing enemy firepower engulfed the Federal soldiers who clung to the ridge and now realized they were in “a kind of cul de sac – a focus of fire” or a killing ground that was taking fire on all sides, except the rear. The simple demonstration was rapidly becoming a nightmare.18

A short time after the First Brigade moved out, Powers’ Second Brigade formed up to cross the Rapidan. Since the pontoon train was stuck in the mud, one half mile in the rear, the possibility of as bridge was now an idle fantasy. As the men approached the river’s edge, Gen. Alex Hays, overcome with excitement and battle euphoria, dismounted and jumped into the river to inspire the men. Down the mud slick banks and into the freezing fast flowing water, mixed with ice and snow, moved the men of the Second Brigade, following their general. Shorter men, who were caught by the current and almost swept away, were held in place by their taller comrades. Generally, the water was supposed to be waist deep, but one man’s waist was another man’s armpit. Rain continued to pelt and sting the faces of the men. With arms uplifted, grasping cartridge belts and rifles, short soldiers attempted to maintain their footing on the muddy river bottom but occasionally they submerged, only to be grabbed and returned to daylight by officers on horseback or taller men. Henry Avis of the 12th New Jersey remembered the river as “so swift it was difficult to keep your feet” and “so cold that it seemed to take our breath.” Once over the ford, the Second Brigade had to cross about 400 yards of open ground in order to form a juncture with Owen’s Brigade, still holding the ridge near the Morton house. Lt. Col. Pierce, in command of the 108th New York, ordered the regiment to traverse the space “at the double quick and in single file”. Artillery shells fell all around the boys from Rochester, but no one was injured. Dr. Wafer watched the smoke from the guns to time his own passage of the gauntlet, however of more concern to the doctor was his horse, ‘Joe Hooker’, who was terrified by artillery fire. Whenever a shell “came screaming” across the field the horse and rider instinctively “cringed” at the noise. Although one shell hit within 50 yards while another ricocheted over them, both surgeon and horse safely joined their regiment at the ridge. In crossing to the ridge, only the 12th New Jersey suffered loss when two shells hit the New Jersey line, clipping off one man’s arm and killing or wounding several others. Around 2.15 p.m., Powers’ Second Brigade reported to Owen who ordered the unit into a line of battle “and placed under cover” of the ridge in the area of the Buckner house.19

Over the next few hours, the men of the Second Brigade huddled in the ravine behind the ridge “protected from the enemy’s shot and shell.” ‘Protected’ was a relative term since anyone who stood upright became a target in the fierce fire fight which raged between the Union and Confederate lines about 100 yards on the other side of the ridge. Wounded skirmishers soon began to drift back to the safety of the ravine while the surgeons scrambled to find treatment areas. Wafer recalled that there “was an old tobacco barn on an exposed hill” to the left of the 108th New York and the men who carried their “comrades from the skirmish line persisted” in taking their injured charges to the barn. Thus the doctor felt compelled to leave the “slight shelter” of the ridge to go to this barn where he and the other surgeons soon became artillery targets for the young gentlemen of the Richmond Howitzers. Just as Wafer successfully extracted “a splinter of shell” from the head of a 1st Delaware soldier, another shell “burst in a muck heap”, within a few feet of the doctor, covering him from head to foot in mud. He must have resembled Al Jolson in ‘Mammy’ make-up since only his eyes and mouth remained visible. Nevertheless, despite his alarming appearance, Wafer managed to get the wounded moving away from the obvious target area just as the Confederate gunners began an extended barrage on the Union position. Federal artillery replied in kind and soon “the field was now covered with bursting shells.” As the fire escalated, Wafer remembered that ‘Joe Hooker’ had been left alone, tied to cherry tree. As his mud covered owner approached, the horse “was making circles round the tree as far as his bridle would let him – neighing or rather screaming frantically”, his habitual reaction “when he found himself alone under fire.” Beneath the mantle of dirt, ‘Joe’ recognized his master and was soon pacified, more or less.20

Shortly after 5 p.m., increased Rebel artillery fire marked the initiation of Ewell’s offensive against the Union line, To the right of the ridge, the Federal skirmishers, now under the command of Lt. Col. William H. Baird of the 126th New York, were driven in by “an impetuous attack” of Rebel infantry. Hays immediately ordered Powers and the Second Brigade to advance “to the crest of the hill” where the 14th Connecticut was dispatched to the right in order to restore the damaged skirmish line. While the Nutmeg State boys moved south-westerly over the ridge towards the Morton residence, the 108th New York, 10th New York, 1st Delaware and 12th New Jersey remained near the crest of the ridge to act as support. Slowly, the Connecticut men shored up the skirmish line and began to push the Rebels back to the Morton buildings. Mid-winter darkness grew in intensity and, as the artillery duel subsided, only the “sharp flashes of the musketry were the only indications of the whereabouts of the enemy.” Confederates lodged themselves in the buildings of Dr. Morton, stubbornly resisting and turning the contest into a vicious fire fight, sometimes “hand to hand” or “in some cases using the bayonet.” Attacking over the open plain cost the 14th Connecticut severely and since they obviously needed help to clear the Morton buildings of Rebels, the 108th and 10th New York began to form up in order to aid their beleaguered comrades.21

Sergeant William Box moved warily along the line of his Company G, crouching to avoid the Rebel fire but urging the men to get up and get ready. Driving cold rain, as well as the freezing water of the Rapidan, had tightened the sergeant’s lower back, where his Gettysburg wounds still troubled him greatly, and the effort to force prone men into standing positions only aggravated Box’s agony. The 20 year old native of Streetsville, Upper Canada, had been wounded in the lower spine and neck six months earlier, on July 2, when the regiment supported Woodruff’s battery. Later, while still recovering the “zeal and ardor” of the young sergeant “was not dampened by the hardships of war or hospital life, and when a general call was made on all hospitals for able men to return to the ranks”, William Box was deemed able to rejoin to his regiment “by concealing the most serious wound, which had not healed, from the examining surgeon.”22 At this stage of the war, the stringency of medical examinations as well as the criteria for fitness depended on the competency, or sometimes the sobriety, of the examining physicians, so Box probably required little guile or “intrigue” to be returned to duty. In the wintry darkness, as bullets whistled past or pitted the crest of the ridge with increased frequency,the sergeant must have pondered whom did he really fool, the doctor or himself? Behind him, he could hear the voice of Lt. Col. Pierce preparing to lead the regiment forward. Suddenly a minié zipped near his right ear, followed by a burning sensation and then a “sharp click”. Part of Box’s ear had been shot off but the “click” was the same rifle bullet striking the face of Pierce. Wafer, as usual, was near the action and in the fading winter light used the illumination provided by the shell fire to probe the colonel’s wound. The round had hit the “side of the face below the left eye, ploughed up” and lodged “in the cavity of the eye.” “His eye bulged out from the socket the size of a hen’s egg.” Momentarily regaining consciousness, Pierce cried out to the men with all the force left him, “Good bye boys I’ve got it right in the brain, close up men – stand up to them – keep the old flag flying”, then quickly swooned once more. Heat and color began to drain from the stricken man but coolly, methodically, the doctor continued his work and found that the ball had displaced the eye. The Lt. Colonel “now commenced to suffer intense agony after recovering from the first shock” but the Canadian surgeon “extracted the bullet in a few minutes –gave him a dose of morphine and a stimulant” then “sent him to the rear feeling more comfortable.”23

Command of the attack now devolved upon Captain Ambrose S. Everett of Co. G, who led the two New York regiments forward. Crossing “several ravines and scaling a high fence” the New Yorkers silently advanced to the aid of the 14th Connecticut. At the Morton house the men “were ordered to fire” and “a terrible volley was poured into the house”, quickly followed by a charge that drove “the enemy from the buildings and the adjacent ground.” This action effectively marked the end of the day’s fight at Morton’s Ford. As the wintry night descended, artillery fire and desultory rifle fire continued well into the evening but, at approximately 11 p.m., Hays pulled his division back across the Rapidan, followed by Webb’s Division around midnight. Warren’s Corps held its position on the northern bank during Sunday, Feb. 7 and returned to camp at Stevensburg later that night. The demonstration was over.24

Once back in camp, the gaiety and tinkling laughter of the officer’s wives which suffused the camp prior to the engagement, was gone, only to be replaced by a shroud of gloom and melancholy as the winter camp was transformed into a temporary field hospital. “The ladies present were hidden from sight in their tents, some of them by the side of mutilated husbands, carried bleeding from the fight to them.” From the vantage point of the camp overlooking the ford, the ladies had been able to watch the advance and some of the battle until darkness fell, then they watched with strange fascination “the flashing of the guns” followed by “the fiery course of the shells”, heard the cheers of the combatants as well as the screams of the wounded and felt the odd “novelty and horror of their situation.”25 Over the next few days, the camp routine returned as the wounded were sent off to Washington or to the corps hospital. Although Lt.Col. Pierce remained in the camp hospital, Wafer was delighted to find that he had improved so much that he could be safely sent on sick leave back to Rochester. Also, the doctor learned, his own request for a leave of absence was granted and he would be going home to Kingston. Thus, on the morning of February 12, 1864, as reveille sounded throughout the camp, Lt. Col.Pierce, accompanied by Dr.Wafer and Captain William H. Andrews of Company C, rode out of the encampment. Pierce, who had refused the use of an ambulance wagon, moved his horse slowly towards the gathering men of the 108th New York, who were so heartened to see him that they cheered both he and the doctor on their way to Brandy Station. Once at the station, Wafer and Pierce left for Washington, while Captain Andrews and other members of the regiment continued on to Rochester to recruit volunteers and the return the remains of the battle flag of the 108th New York. “The flag was merely a bunch of silken rags bound to a staff” that had splintered and “would no longer bear unfurling being pierced by many bullet holes.” Since it was the second of only four state banners issued to New York regiments after Lincoln’s call for more men in 1862, returning the remains of so valuable a relic, entrusted to the care of Color Sergeant Tom Crouch of Company D, became paramount for the boys from Rochester.26

Demonstration on the Rapidan, as the conflict at Morton’s Ford came to be labeled, left a bad taste for everyone directly involved. On the strategic level, nothing had been accomplished, except to alert Lee to a possible passivity on the part of his troops in the Rebel fortifications. Lee would not get caught again. Sedgwick complained that one “result of the co-operation with General Butler has been to prove that it has spoilt the best chance we had for a successful attack on the Rapidan.” Butler’s freedom raid, of course, failed miserably, not getting to within 12 miles of Richmond, and was virtually scuttled before it started when a Union deserter revealed the cock-eyed plan to the Rebels. In a bitter and sarcastic mood, the Second Corps historian wrote:

It is needless to say that General Butler’s movement on Richmond, from the south, amounted to nothing. The only report which the writer ever saw of his operations acknowledged the loss of six forage caps by the men of his command.

In stark contrast, Warren lost 255 men in the fruitless effort, nearly all of whom were lost from Hays’ Third Division and that statistic, in turn, generated another bad taste, but this time on the tactical level.27

In his report, written six days after the return to camp, Hays implied that his division had been handcuffed by the lack of aggression on the part of the corps commander. He opined that if “supported by our whole corps I have not the least doubt that we would have been enabled to capture the whole force of the rebels, including camps and artillery with less loss than we have suffered.”28 The last phrase seems straightforward but is heavy with innuendo. Because his troops had to sit nearly all day behind a ridge, taking fire from three sides and their only offensive display was a reinforced skirmish line, the division took more casualties than it would have taken if allowed to attack. His comment was a not-so-subtle shot at the Second Corps Commander, who certainly read it that way. Warren, in his report, written in the third week of March and six weeks after the demonstration, decided to educate his enthusiastic underling. With typical professorial condescension, the corps commander logically and painstakingly corrected the mistaken opinion of his “sanguine, able and reliable”officer and dispelled the impression “ that we did not attempt more.”29 Warren’s shrewd detached analysis illustrated perfectly one of the problems of the Army of the Potomac. High ranking general officers could always find a plethora of reasons for not doing something, whereas risky action seemed like anathema to them. Given previous battles and leadership, Warren was probably correct in his interpretation on this occasion but the fact that they did find a chink, even temporarily, in Lee’s armor then sat and did nothing, shows the mindset that plagued that army since McClellan’s reign. At Morton’s Ford, Hays, as usual, was caught up in the fight where he saw an opportunity and wished to exploit it. For a temperament such as Alex Hays, to sit there, taking a pounding was intolerable yet, ironically, the corps commander had forced the identical scenario on to him that Hays had forced on to the 108th New York at Gettysburg when they lost half of their men. More than likely, the irony was lost on Hays.

Not content with aggravating the corps commander, Hays next took aim at the 39th New York (Garibaldi Guards) and the 14th Connecticut. Both regiments, he argued, since they consisted “of conscripts or substitutes”, faltered under fire and thereby caused the “extremely long list of casualties.” Neither regiment said anything at the time, but 42 years later, Charles Page, in his regimental history of the 14th Connecticut unloaded a lot of repressed hostility in his highly vitriolic account of the action at Morton’s Ford. Once across the river, Page claimed that Hays “rode back and forth upon his galloping steed, his reckless manner and incoherent language indicating that he had added two or three extra fingers to his morning dram.” He went on to attack the other accused regiment, the 39th New York, “probably the most unfit troops in the whole corps”, who “were mostly foreigners” and gave way under fire. Regiments in his own brigade fared no better when Page suggestively pointed out that the men of the 14th Connecticut had to step “over the prostrate forms of the Twelfth New Jersey” in order to advance into the fight. While they fought at the Morton House, Hays rode up, entered the house and proceeded to curse them out “with various expletives” and ordered them to advance. According to Page, this order led to the capture of Captain Frederick B. Doten, and six other members of Company F, 14th Connecticut. Later on, to add injury to insult, Hays ordered the 108th New York to fire on the Nutmeg boys, who, in the winter darkness, he believed to be Rebels “and how many of the brave Fourteenth fell by that stupid drunken order will never be known.” Not only was Hays, the division commander, drunk but so was the brigade commander, Col. Charles Powers of the 108th New York, who was “so seriously indisposed as to be unable to sit upon his saddle or even walk about, but sat listlessly in a large arm-chair brought from one of the neighboring houses.” Just how Powers managed to sit in a comfy chair while under fire from three sides, without any one noticing, was never explained. Later in the day, Powers compounded his transgression when he assigned the Connecticut troops to picket duty, shortly after midnight on February 7. “This was cruel and wicked as there were many troops that had not seen action during the day, but such was the fortune of the brave old Fourteenth.” Finally, Page brings out the topper: the Second Corps Commander, Major General Gouvenour Kemble Warren, was also drunk and could not attend to the battle until late in the afternoon when he sobered up. So, according to Charles Page the 14th Connecticut did most of the significant fighting and the commanding officers of the Federal army entered the demonstration at Morton’s Ford in a condition similar to Bob McIntosh of the Richmond Howitzers, they were all half cut.30

In the last week of February, the Second Corps’ gala ball, the social event of the season for the officers and their wives, took place “at the Thom House on Cole’s Hill. Adjoining the house, a dancing hall which required 1200 feet of lumber to floor” was completed by the 22nd of February so that the ball could coincide with Washington’s Birthday. Of course, the enlisted men provided the muscle but could only watch the upper crust at play. They “were banned from attending, save for the bandsmen who provided the evening’s music. This caused a certain amount of resentment among the rank and file who enjoyed no punch or music and whose womenfolk remained hundreds of miles away.” Numerous luminaries, the vice-president and his daughter as well as a governor and congressmen attended while orchestral music filled the night air. $2200 covered the catering bill from Gautier of Washington, which was offset by a minimum subscribed “donation” of $20 per officer, “according to rank or position”. In order to maintain proper social hierarchy and decorum, not all Second Corps officers were expected to attend since only those solicited to pay the subscription were invited. Clearly, an officer’s commission was not an automatic social passport into the rarefied atmosphere of the upper echelons of the army as Meade’s own staff officers, except his son, found out.31 Long through the night and the early morning hours, the bands played on as officers glittered in their dress uniforms and the ringing laughter and the perfumed swish of ladies’ gowns suffused the gaiety of the candlelit soiree. For an evening, at least, the war seemed far away and remote, not just 12 miles south at the Rapidan , where the pickets were doubled and the Second Brigade of Hays’ Division stood ready, in case the enemy dared to shatter the bubble-like dream of the Second Corps Ball.

As the winter of 1864 lurched slowly towards spring, the number of ladies in the camp grew, instead of diminished. Officers managed to extend the wives’ 20 day visiting permits to 40 days or even 60 days.32 Francis Wafer, having survived a train derailment near Albany, returned to the camp of the 108th New York on February 28, where he found a package addressed to him “containing a beautiful pair new pair of cream colored pants”, a gift worth at least five dollars. No note identified the donor but the doctor strongly suspected Lt. Col. Pierce, whose life he had saved at Morton’s Ford. The surgeon was well pleased that “the gaiety of the camp had rather increased” with the continued feminine presence, even though Mrs. Grassie, the chaplain’s wife, chided the steadfast bachelor for not acquiring a wife while on leave. His visit home had been a strange experience. During his absence from Kingston, the doctor had become a veteran and, like most veterans, was unable or unwilling to articulate the reality of his experience to his friends and loved ones. While at home, Wafer “sedulously kept from my friends as much as possible the knowledge of the danger my service exposed me to” and was just as evasive about his future involvement since he had no desire for his friends and relatives to regard him as “a most determined suicide.” As a Canadian, Wafer owed allegiance to England and the Queen and thus could not be forced to return to the war, but the visit home some how galvanized him into a “firm determination to see the end of the war or myself.” After months of marching, fighting and suffering together, a bond, which only war can render comprehensible, existed between the doctor and the men of the 108th. They were now also part of his family and he would not, could not let them down.33

The cool winds of March blew in once more and brought with them the festive familiarity of the St.Patrick’s Day celebration, traditionally sponsored and promoted by the Irish Brigade. Entertainments, such as horse races for the officers, sack races or the ever popular “catching the soaped pig” for the enlisted men, occupied the time from mid-morning to the late afternoon on March 17. A boxing match, involving twelve opponents “with gloves on” can only be imagined as can the race to climb a greasy pole “for 20 dollars and a furlough of 20 days.” And as the Irish spirit flowed freely over and through the flushed contestants and celebrants, during this “most gay and lively” holiday for the Apostle of Ireland, those same cold winds brought irrevocable change for the Army of the Potomac.34 No longer would the army go into battle with five corps. Instead, there would be only three corps. Remnants of the proud old First Corps, virtually shattered at Gettysburg, were consolidated into a division and assigned to the Second Corps as the First Division, under Francis Barlow. The Third Corps was also split up and, once the fragments from the terminated corps were incorporated, the divisions in each of the surviving corps were reshuffled in order to handle the increase in manpower. In the Second Corps, Hays’ Third Division was collapsed and added to the Second Division, now under John Gibbon, fully recovered from his Gettysburg wound. Webb, former temporary commander of the Second Division, reverted to commander of the First Brigade, Second Division, whereas Hays was also downgraded to brigade command in the newly incorporated Third Division, commanded by David Birney, formerly from the Third Corps. Finally, the Fourth Division under Gresham Mott rounded out the new Second Corps. As far as the Rochester Regiment was concerned, their brigade was merged with Sprig Carroll’s brigade to form the Third Brigade, Second Division, Second Corps consisting of: the 14th Connecticut, 1st Delaware, 12th New Jersey, 108th New York, 10th New York Battalion, 8th Ohio, 4th Ohio, 7th West Virginia and the 14th Indiana. Some high ranking officers were now out of a job. Major General George Sykes was dispatched to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas and out of the war. His replacement would be the man he failed to support at Bristoe Station, Major General G.K. Warren, temporary head of the Second Corps. Winfield Scott Hancock, still suffering from his Gettysburg wound, would resume the command of his old corps with the departure of Warren. The men of the 108th New York learned that Major General William H. French, their first division commander, who had blundered during the pursuit of Lee as well as at Mine Run, was sent to Philadelphia and mustered out of volunteer service on May,6, 1864. John Newton, former commander of the now defunct First Corps, a man appointed by Meade after the death of John Reynolds, was asked “to repair to Cincinnati, Ohio,” and await service with General Sherman.35 With the departure of their officers and the loss of their corps, the disenfranchised men were neither pleased nor willing to re-locate. Although these veterans of numerous battles were allowed to maintain their original identity, designated by corps badges and insignia, within their new units, some refused to go without protest into the amalgamation. Wafer recalled that there “was much dissatisfaction among the troops of all ranks belonging to the consolidated Corps – that portion of the 3rd assigned to our Corps especially were highly indignant when ordered to wear the trefoil, the badge of the 2nd Corps -some went so far as to refuse, others sewed it upon the seat of their pants by way of derision.” With regard to the latter group, the doctor wryly observed that “the badges on those last were just where the enemy were most likely to see them.” A compromise was struck when the refugees were permitted to wear the diamond, the Third Corps emblem, as their division badge in the Second Corps.36 While members of the re-structured army continued to gripe and bicker, the most significant change for the Army of the Potomac in the spring of 1864 had already occurred earlier in the month when the newly appointed general of all the Union armies blew into town.

Ulysses S. Grant was confirmed as Lieutenant General on March 2, 1864 and summoned to Washington the next day to receive his appointment. Six days later, President Lincoln presented the western general with his commission and Grant was now the highest ranking officer in the Union army. March 10th brought a brief visit to the Army of the Potomac from the new commander, who quickly returned to Washington and thence to the west in order to finalize his command arrangements. During the brief visit, Grant spoke with Meade who informed the Lieutenant General of his proposed changes for the army and wondered if Grant wished to make one more change – namely replacing the commander of the Army of the Potomac. The westerner assured Meade about his position and “that I had no thought of substituting any one for him.”37 Grant’s return on March 25th to his headquarters at Culpeper Court House barely caused a stir in the ranks of the principal army of the Republic. After almost three years of fighting, a new commander meant very little now to the men, except more battles and death. Through the rose-colored glasses of hindsight and thirty years after the fact, the historian of the 108th New York, George Washburn, rhapsodized that the advent of Grant “so enthused the men with confidence of success and inspired them with renewed indomitable zeal to do or die.” After Chancellorsville, the closest Washburn got to the war was the corner of “15½ Street and Pennsylvania Avenue” in Washington, D.C. so his “enthused” account of Grant’s arrival is suspect to say the least. Dr. Wafer made no special mention of the new commander, other than acknowledging his presence at a review and certainly noticed no renewal of fighting zeal in the men. The ever-waspish and arrogant Colonel Charles Wainwright seemed positively delighted that “there was no enthusiasm shown by the men on the arrival of their new commander” and only wished for some Virginia mud to welcome the western general to the east. Wainwright, a self-styled aristocrat, egotistical and vain, was further horrified by Grant’s “stumpy unmilitary, slouching and Western-looking” appearance which did nothing for the “pluck” of the troops. The rich New York Colonel of artillery may have been a good artillery officer, but, in his diary, his human side appears shriveled, petty and jealous. Upon his return to the 108th New York on the eve of the Overland Campaign, Lt. Col. Francis Pierce presented a more balanced perspective on the arrival of the Lieutenant General:

I find that great confidence is reposed in Gen.Grant by both officers and men. There is no enthusiasm– in fact I think that no Gen. will ever again be regarded as McClellan – not even Mc[Clellan] himself should he be restored – yet there is a deep feeling of trust and confidence pervading the army as near as I can learn. Many are withholding the expression of opinion and are waiting to see what will be accomplished.

In his letter, Pierce was describing the reaction of a mature army, no longer a group of idealistic youngsters devoted to a charismatic, yet ineffectual, leader but rather battle hardened veterans, grown men who needed competent, no nonsense leadership. A young recruit in the Eleventh New York battery, perhaps parroting the comments from veteran gunners, explained that “Grant’s name aroused no enthusiasm” since the Army of the Potomac had passed the enthusiastic stage and was patiently waiting to be led to victory or to final defeat. A veteran of the 10th New York, the National Zouaves, felt that the time for demonstrations and pomp were over “ since the tinselled(sic) days of 1862, the war had settled down to a stern business, which engrossed the attention of all and allowed no time or desire for superficial manifestations of admiration for a leader. None doubted the courage of Grant or Meade, or their willingness to lead personally if a battle crisis demanded; but their presence among the men, during a campaign, was simply noted, and that was all.” Unmilitary and slouchy, Grant may not have been what Lincoln’s principal army wanted, but his style of warfare and determined leadership was surely what the eastern soldiers needed in order to bring the war to an end.38

Shortly after the St.Patrick’s Day festivities, the ladies began to leave the camp to return home and await the fates of their husbands. On April 7, Meade issued General Orders Number 17, which set April 16 as the deadline for all non-combatants to leave the camp and revoked the authority given to commanders to grant furloughs or leaves of absence.39 During the final weeks in camp, the army “put on its most warlike aspect” to enter the upcoming campaign and, at 4.30 on the afternoon of May 2, about 30 hours before Grant initiated his offensive, nature seemed to send its own sign to the Second Corps in the form of “a reddish brown cloud of immense extent, heighth (sic) and density” moving “from the Blue ridge towards the camp.” To the northern soldiers, the occurrence was a mere novelty, but “to those intimate with such phenomena it was at once recognized as a mass of earth or dust raised by a tornado.” Suddenly the roar, “distant and indefinable” was heard growing in intensity into a tremendous thunder, like the rumble of a thousand railway cars. Horses nervously pawed the ground, pulled on their tethers and looked frantically for a way to escape. Soldiers stood open-mouthed and awestruck at the power of nature and the terrible beauty of the sunlight shining through the funnel and highlighting the particles of swirling red dust. A “sudden twilight of darkness” was upon the camp as the wind burst “with a crash that was positively deafening and with a force” of enormous power. Those who could not grasp onto something quickly lost their footing in the blast. Coincident with the wind, a shower of “earth and small stones in heavy masses” pelted the men, making any effort to open the eyes impossible. “All tents, not held by hands, disappeared in the nearest piece of woods – the log huts blown to pieces – the logs rolling, bounding over the earth until they met some solid obstruction.” Desperately, men latched onto their tents, strained to keep hold of their most highly prized possessions, but even so, they failed to keep the tents upright. Chimneys, made of empty barrels, flew around in a senseless swirl, bouncing off people in a mad race to follow the tents into the woods. Nature’s fury continued for 20 minutes, then, just as suddenly, became subdued into an evening rain. To a practical and prosaic soldier of the 108th New York, the storm “was quite a hurricane” and “was the hardest wind” he had “ever experienced” but nothing more. For the surgeon of the regiment, the dust cloud “gave the appearance of an enormous and uncontrollable wave tinged with blood.” 40 In hindsight, the occurrence on May 2nd could be seen as portentous. The dust cloud that blew through the camp of the Second Corps was the wind of violent change and destruction and no one would escape its impact. For the next 12 months, Grant would metaphorically take his army, especially the Second Corps, into a tornado of combat, marching, mutilation and death, plumbing the dregs of horror but re-emerging in victory and triumph.

Endnotes

1 O.R. 29,2, p.575 ; Porter-Letters, Jan. 10,1864 ; Wafer-Diary,p.98.

2 Longacre, To Gettysburg and Beyond, p.168; Porter-Letters, Jan.10,1864.

3 Robert S. Holzman, Stormy Ben Butler(New York: Collier Books, 1961),pp 94,107; Generals in Blue, pp.60-61; Mary Chestnut, A Diary From Dixie, reprint Gramercy Books (New York: Gramercy Books,1997) p.294. Even Unionladies seemed to share the contempt for Butler with their southern counterparts, see Maria Lydig Daly, Diary of a Union Lady, edited Harold Hammond(Lincoln : University of Nebraska Press,2000) pp. 313, 333.

In a more recent and revisionist biography of Ben Butler, a number of the accusations associated with Butler are presented as fiction, see Dick Nolan, Benjamin Franklin Butler, The Damnedest Yankee (Novato,CA.:Presidio Press, 1991). However the hatred generated by Butler is clearly obvious in an article written ten years after his death by Captain James Dinkins, “Lest We Forget Benjamin Butler”, Southern Historical Society Papers, 52 vols. (Millwood, New York: Kraus Reprint Co.1977), vol.30,pp.188-195. Hereafter cited as SHSP followed by volume number and page number.

4 Dick Nolan, op.cit.,pp.241-242.

5 Generals in Blue, p.558

6 North Carolina Regiments, vol.III, p.713; O.R.29,1,p.912 ;O.R.II,6,pp.877-878,1128.

7 O.R.II,6,p 846.

8 O.R.,29,2,pp. 746,873,882.

9 O.R.II,6,pp.845,858.

The confusion around the identity of the executed man arose from the fact that the Fifth U.S. Colored was recruited in Ohio and spoke of themselves as the Fifth Ohio. Butler referred the matter to the General in Chief, Henry Wagar Halleck, for further action but, typically, Halleck, the Teflon-man, wanted to be responsible for nothing ,so that’s what happened, nothing! Pickett moved up the scale from single hangings to mass hangings in February of 1864 and both he and Federal general, John James Peck engaged in heated, but futile, correspondence over Pickett’s record as hangman. See: O.R.II,6. pp.865-870 ; Gerard A. Patterson, “Hangman Pickett”, America’s Civil War, November, 2002,pp.38-44.

10 O.R.,33,p.519.

11 O.R.,33,pp.502,506-507 ;Wayne Mahood, “Tiger at Morton’s Ford” Civil War Times, vol. XLI, issue #7(Feb 2003) p.26.

12 O.R.,33, pp.512-515, 518, 524; Theodore Lyman, With Grant & Meade, p.68. Hereafter cited as Lyman.

13 O.R.I, 33,pp.129,132,134-136,139.

14 Wafer-Diary,pp.99-100 ; O.R.,36,pp.114, 133.

15 O.R.33, p.115 ; Walker,Second Corps,p.394.

16 William Meade Dame, From the Rapidan to Richmond (Baltimore: Green Lucas Co.,1920) rpt. Owens Publishing Co.(Richmond,Va.:Owens Publishing Co.,1994) pp.40-42,63 Hereafter cited as Rapidan to Richmond ;O.R.,36, p.142.

17 O.R.,33,pp.127,142,

18 O.R.,33,pp.115,133,142-43; Rapidan to Richmond, p.42

19 Dunn Browne, p.222 ; Page,14th Connecticut,pp. 217-218 ; Sawyer, Military History of the 8th Regiment Ohio Vol. Inf’y, p.155 ; Galwey, The Valiant Hours,pp.187-88 ; Mahood, Written in Blood, p.214 ; To Gettysburg and Beyond, pp.170-71; O.R.,33,pp. 129,133 ; Wafer Diary, pp.100-101.

20 !4th Connecticut, p.218 ; Wafer Diary, pp.101-102.

21 O.R.,33,p 129 ; 14th Connecticut, p.220

22 108th New York,p.228.

23 Ibid., pp.155-56 ; Wafer-Diary,pp.102-103.

24 O.R.,33, pp.132,115.

25 Wafer-Diary, p.104 ;14th Connecticut,p. 229.

26 Wafer-Diary, pp.104-105 ; 108th New York, p.17 ; Palmer-Diary,p.21.

27 O.R..33, pp.532, 143-44; Second Corps, pp.395-96.

Butler claimed that Private William Boyle had been allowed to escape by a Private Abraham of the 139th New York and had revealed all the details of the plan. However, Butler’s security must have been leaky to say the least, since General Lee, in a letter to Jefferson Davis, suspected Butler’s ploy nearly three weeks before he attempted it (O.R.,33,p.1081).

28 O.R.,33,p.127

29 Ibid., p.115.

3 14th Connecticut, 218-224. Page’s commentary on Morton’s Ford is generally acknowledged as an important primary source on the battle/ demonstration. However, the account was published 42 years after the event and his claim that nearly all the major Union leaders were drunk and/or incompetent, except anyone associated with the 14th Connecticut, does sound suspicious. Samuel Fiske, captain of Company G, 14th Connecticut, makes no mention of drunkenness in his first hand account, written two days after the attack (not 42 years!) and makes no mention of extraordinary behaviour on the part of Alex Hays, nor any losses due to friendly fire from the 108th New York (Dunn Browne, pp.222-223). Understandably none of the official reports mention drunkenness, but they don’t mention the incident of friendly fire either. Theodore Lyman, Meade’s Aide, who showed a genuine admiration for Hays, described the general’s heroic antics but never suggested that liquor was the fuel (Lyman, pp.42,82, 92,109). Dr. Moses Wafer was quite familiar with Charles Powers and, based on his own family history, was quite sensitive to the issue of alcoholism, yet, in his diary he recorded nothing of a drunken brigade commander sitting in an armchair, in a whisky haze, oblivious to the gunfire around him. As to the third member of the alleged drunken trio, if Morris Schaff is to be believed, Warren preferred a round of limericks to a round of liquor (Schaff, Battle of the Wilderness, p.30). Probably none of these men were adverse to alcohol, but to portray them as drunken sots leading men to death, without substantial corroboration, is not justified. In terms of loss, the 14th Connecticut had 115 casualties, almost half [45%] of the total loss for the Second Corps which does suggest that they were in the thick of the fight, but the regiment with the next highest loss(36) was the 39th New York – “the most unfit troops in the whole corps” according to Page (O.R.33,p.118). Consequently, Page’s account may indeed be valuable, but should be used judiciously. For an excellent discussion of the entire episode, see Wayne Mahood, “Tiger at Morton’s Ford”, pp.24-31.

31 To Gettysburg and Beyond, p.173-4 ; William W.Potter, One Surgeon’s Private War, ed. John M.Priest (Shippensburg, Pa.: White Mane Publishing,1996), p.93 ; Dunn Browne , p.229 ; Lyman, p.75.

32 Potter,op.cit.,p.94.

33 Wafer-Diary, p.106 ; Wafer-Letters, Feb.29,1864.

34 Wafer-Letters, March 20/64; William Corby, Memoirs of Chaplain Life, ed.L.F. Kohl (New York, Fordham University Press, 1992),p. 139

35 O.R.1,33,pp.638-39,722 ; Generals in Blue,p.162.

36 Wafer-Diary, p.109.

37Grant, Personal Memoirs, vol.2, pp.114-155, 117.

38 108th New York,pp.65,216 ; Charles S.Wainwright, A Diary of Battle ,pp. 338-39; Porter-Letters, May 3, 1864, F.E. Pierce to Mr. Samuel Porter ; Frank Wilkeson, Turned Inside Out (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press,1997), p.37 ; Charles W. Cowtan, Services of the Tenth New York Volunteers(New York : Charles H.Ludwig Publisher,1882),p.265. Hereafter cited as 10th New York.

39 Frank A. Boyle, A Party of Mad Fellows (Dayton, Ohio: Morningside House Inc.,1996), p.314 ; O.R.,33.pp.816-17.

40 Wafer-Diary, pp. 109-110 ; Bennett, Sons of Old Monroe, p349 ; 14th Connecticut,

p. 232 ; Arabella Willson, Disaster, Struggle, Triumph, The Adventures of 1000 “Boys in Blue”(Albany: The Argus Company,1870),rpt.Higginson Book Co.(Salem, Mass.: Higginson Book Company,1998),pp. 239-240 ; 108th New York, p.134 ;To Gettysburg and Beyond,pp.180-81; Waitt, Nineteenth Massachusetts,p.302 ; John L. Parker, Henry Wilson’s Regiment, History of the Twenty Second Massachusetts (Boston : The Regimental Association, 1887),rpt. Butternut and Blue(Baltimore : Butternut and Blue,1996), p.399-400 ; Elisha Hunt.Rhodes, All For the Union, ed. Robert Hunt Rhodes (New York: Orion Books,1991), p.143. All these sources mention the ferocity of the storm.