Chapter Eight

Rochester's Forgotten Regiment:

The 108th New York In The Civil War

By Terence G. Crooks

Chapter Eight:

And The Angels Of Death Danced

Before midnight on May 3, 1864, the Army of the Potomac started on what would become the first stage of the final prolonged campaign in the east. In the silent darkness, the surgeon of the 108th New York wandered through the regiment’s dismantled camp which had been home for many months, now reduced to cabins without canvas roofs, empty log huts and the smoldering ashes of dinner fires. Francis Moses Wafer felt an enormous sense of emptiness and abandonment hanging like a shroud over the vacated winter quarters of the Rochester Regiment and he also felt the need for prayer. He stepped into the roofless log structure that the men had built for a chapel but became aware that he was not alone. Kneeling by the fireplace, illuminated by the faint flickering glow of the dying embers, Thomas Grassie, chaplain of the 108th, was deep in prayer. As a Catholic, the doctor’s first impulse was to leave thePresbyterian reverend alone in his chapel, yet religious difference seemed trivial when compared to the enormity of the upcoming campaign so the doctor remained, prayed and hoped “although being of different creeds that we were both heard.” 1

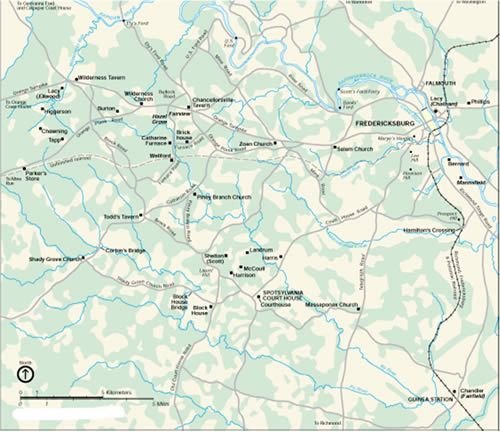

Overview Map of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Battlefields.

(taken from National Park Service Website – see Bib. for full citation- grey areas represent heavy vegetation)

All day of May 4th the advance continued over the Rapidan with two columns, the Fifth and Sixth Corps, crossing at Germanna Ford and, farther to the east, the Second Corps at Ely’s Ford. Both movements were preceded by cavalry. Burnside’s Ninth Corps, technically under Grant’s control, was and was not part of the Army of the Potomac. At this point in time, Grant could give orders to Burnside but Ambrose Burnside did not have to take orders from Meade, the titular commander of the army. With Grant accompanying the army, the role of Meade became nebulous at best and non-existent at worst, especially with Burnside’s Corps as some sort of independent unit, loosely attached to the Army of the Potomac via Grant. The Lieutenant General’s failure to take final and unequivocal control of the army, thereby clarifying the command structure, has been cited as a significant cause for the misfortunes that befell his army over the ensuing weeks2. Despite the unwieldy chain of command, Grant’s opening move reflected his intent to force Lee into an open confrontation upon favorable ground where, theoretically, the Federals’ enormous edge in manpower and artillery should overwhelm the Army of Northern Virginia. While the Germanna Ford column skirted Lee’s Mine Run fortifications Hancock’s Corps, crossing at Ely’s Ford, would swing around via Chancellorsville to form the southern end or left of Grant’s force, effectively turning Lee’s right flank. Once aligned and out of the Wilderness, all three corps would advance west along the Orange Turnpike, the Orange Plank Road and the Catharpin Road in roughly a north-south formation thereby forcing Lee out from behind Mine Run and into destruction.

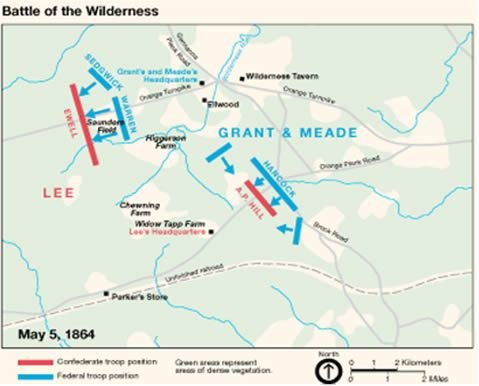

(Map taken from National Park Service website)

Of course, the entire plan depended on Lee’s cooperation as well as the flawed assumption that Lee’s men could not react in time until Grant’s army was through the Wilderness and in the process of turning the Rebel flank.3Typically, Lee proved to be uncooperative and attacked the Union Fifth Corps before it traversed the waste land of scrub forest. In fact, by the end of fighting on May 5, Lee had not only shredded Grant’s plan but early in the battle had come within a whisker of splitting the Army of the Potomac into two. While Ewell’s Confederates held the Fifth Corps in place on the Orange Turnpike, farther to the south along the Orange Plank Road A.P.Hill’s Third Corps almost flanked Warren’s men when he moved east towards the junction with the Brock Road which, if achieved, also would have isolated Hancock’s Corps, the left or southern flank of Grant’s army. Getty’s Division from Sedgwick’s Sixth Corps was dispatched to Brock Crossing, the intersection of the Brock and Orange Plank roads, to thwart Hill’s intention of splitting and flanking the Union army. Getty arrived in time to hold the road junction but nevertheless was faced with the daunting prospect of confronting the entire Third Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia with a single division. At approximately 11.00 a.m. Hancock’s Second Corps which was heading south on the Brock Road to Todd’s Tavern, was informed of the disaster to the north and ordered to reverse its movement. Quickly changing direction, the Second Corps moved northward to the critical intersection. At 2.00 p.m. Birney’s Division arrived first and formed along the Brock Road, his right connecting to Getty’s left, followed by Gibbon then Barlow. Gibbon detached Sprig Carroll’s Third Brigade, which included the 108th New York, and sent it to General Birney about 3.30 p.m. Birney placed the brigade on the right side (north) of the Orange Plank Road in preparation to relieve Getty’s men who were still engaged with Heth’s Division of Hill’s Corps.4

As the 108th New York formed a battle line north of the intersection, the men instinctively began “to build rude breastworks of logs and earth.” Nearly all of Carroll’s regiments did likewise which was fortunate indeed since these fortifications at the crossroads would play an important role over the next day or so. Just before the advance began, Dr. Wafer searched for his orderly, George Vaughn, who was responsible for the surgeon’s field knapsack and medical pack horse and who had became separated from the doctor during the rapid movement up the Brock Road. After riding back a mile or so, he and Vaughn were re-united but as the regiment prepared for combat the doctor now faced a dilemma. He had been given the choice to retire to a place of safety “where the Chief Surgeon of the Corps would establish his field hospital” or to serve near the front in the thick of the fight. Wafer “felt a great historical day had arrived” and he wished to share the fortune of his regiment. But at that moment of choice, his eyes locked with those of George Vaughn. Vaughn had been recently assigned to Wafer and the doctor knew Vaughn was married with young children. “This reflection made me decide to not take him into the fight so I shouldered the knapsack myself and sent him to find the field hospital with the other attendants, giving him my horse in exchange.” 5

When ready, Carroll’s Brigade moved westward in three lines along the right of the Orange Plank Road. The New Yorkers were the right flank of the second line, with the 1st Delaware in the middle and the 14th Connecticut as the left along the plank road. After moving no more than fifty yards westward “down a gentle slope, the brigade came under volley fire from the Confederate riflemen “who were in position on the opposite edge of the swamp”.6 Over the next several hours, Stone’s Confederates from Heth’s Division gradually gave ground and were backed up from the key intersection. Hancock, who personally witnessed the “severity and obstinacy” of the fighting, provided a cool and calm example for the men. Without concern for himself, he rode among the men “speaking kindly and encouragingly to them and settling them to work to build log breastworks.” Hancock’s attitude was contagious and spread to the officers in his command. Sprig Carroll was wounded in the action along the plank road but, despite the efforts of Dr. Wafer to dress the flesh wound in the upper part of his right arm, the colonel refused attention and warned the doctor to find a “sheltered position” for his own safety since the fight was about to turn “too hot.” With his “roughly bandaged” arm in a crude sling, the colonel thanked the doctor then continued to walk along the line, “encouraging each battalion as he passed.” With Carroll’s advice in mind, Wafer noted that avoiding the heat of battle was easier said than done since the land, though densely overgrown, was mainly flat in the immediate area. However he found “a large old fallen tree about one hundred yards in rear of the Brigade” and here, until darkness, he set to work on “halting and dressing all the wounded” who were “walking or being carried to the rear.”7

Later in the day, as darkness approached and the fight wound down, the 108th New York learned of the loss of their former general officer, Alexander Hays. Hays’ Brigade from Birney’s Division had fought on the northern side of the Orange Plank Road in support of Getty and had preceded Carroll’s Brigade into action. As could be predicted, Hays was killed while personally rallying an infantry regiment for a charge. “He had paused briefly near the 63rd Pennsylvania and while in the midst of a rallying cry, an enemy bullet tore through his skull. The sound was distinctly heard above the deafening tumult.” When informed of Hays’ death, Grant was visibly shaken but said nothing. After a moment of silence, he said, “He was noble man and gallant officer. I am not surprised that he met his death at the head of his troops; it was just like him.”8 By 8.p.m. on the evening of May 5, the fight along the Orange Plank Road began to subside as the Second Corps managed to secure the vital road crossing by pushing Hill’s exhausted troops back “almost a quarter of a mile from that position.” During the night of the 5th Grant intended the melee to continue and issued Hancock orders to attack A.P. Hill at 5.00 a.m. the next morning to finish the rout started on the previous evening.9

At 4.30 a.m. of May 6, as part of Hancock’s offensive to smash A.P.Hill’s Third Corps, Carroll and his men moved westward along the right or northern side of the Orange Plank Road. Quite easily they advanced over the hilly ground with the enemy appearing to retire before them, leaving only their dead and wounded. Upon “hearing rapid and heavy musketry on the left of the plank road”, Carroll crossed to the south side and marched “towards the firing.” But before he could become engaged, he was ordered by Birney to return part of his force to the right side. He detached the 8th Ohio, 14th Indiana and the7th West Virginia who were soon separated from the rest of the brigade, “flanked by a vastly superior force of the enemy, and, after losing heavily, forced to retire.”10 Carroll’s remaining force took on the enemy south of the road until late in the morning. At first, the Union thrust seemed to work like a charm. Hill’s “Confederates were driven more than a mile through the forest almost to their wagon trains.” General Lee was so distraught by the sight of his army running that he “threw himself among the troops and used every exertion to rally the broken brigades which had recoiled from that terrible assault” of the Federal troops. Needless to say, Hancock was ecstatic. To Meade’s aide, he expostulated, “We are driving them sir; tell General Meade we are driving them most beautifully.”11 And, indeed the men of the newly re-furbished Second Corps did push Hill back for some distance and in some disorder. With their new state flag to replace the tattered remnant sent home in February, the 108th New York advanced in the second line, probably on the left side of the brigade.12 Twenty-one year old Sergeant Charles Bailey of Co.F carried the national flag while “the prize banner just received from the State” was held by twenty-three year old Thomas Crouch, who had carefully returned the original flag to Rochester earlier in the year. After being detailed to recruiting duty for two months, Crouch brought back recruits as well as the new flag of the 108th New York.13 Both flag bearers proudly marched as best they could through the dense forest for about a mile or so but then came to an abrupt stop. Hill’s Confederates had been reinforced by Kershaw’s Division of Longstreet’s First Corps -Lee’s Old War Horse was on the field and Hancock’s attack was running out of momentum. The tide began to turn.

Fighting in the Wilderness beggared description. Modern maps of the battle that use rectangles to represent the precise movement of units and the orderly flow of battle, inadvertently present a simplified and, perhaps, misleading picture. This battle was a confused whirling affair in tangled brush, impassable thickets and dense secondary growth forest. Battle lines were in name only. Units intermixed, became lost, disoriented, stumbled into and out of vicious firefights, advanced, retreated or fled in reaction to the men immediately around them. When a good deal of the battleground caught fire, roasting wounded from both armies, the intense smoke only added to the confusion. This was no Napoleonic set piece engagement but rather like a street brawl or “simply bushwhacking on a grand scale where all formation beyond that of regiments or companies was soon lost.” A veteran of the Texas Brigade, captured during the counterattack that stopped the Federal drive in the morning, perfectly caught the essence of the fight when he lectured his captors:

It ain’t no battle! It’s a worse riot than Chickamauga was! You Yanks don’t call this a battle do you? At Chickamauga There was at least a rear but here there ain’t neither front nor rear. It’s all a ____ mess! And our two armies ain’t nothin’ but howlin’ mobs.

An unnatural twilight seemed to engulf the field and augment the already gloomy thickness of the pitchy woods but lack of light did not prevent the soldiers from finding each other. While Wafer dressed the wounded, he watched troops to his left “within speaking distance” of each other, resort to hand to hand combat, “pouring their fire into each other with a fury perfectly hellish” until the woods were “one continuous blaze and roar.” The doctor recalled “the wild and bloodcurdling yells of the enemy, as some part of our line was literally blown away” followed by “the deep British-like cheer of our troops” then “another thundering outburst of musketry from both sides as a fresh battalion or brigade rushed forward to reclaim the lost ground then again the same act repeated” along a battlefield “swimming in fire and blood”.14

On the front of the 108th New York, the fight in the close undergrowth became desperate. In the morning fog and smoke, friend could not be delineated from foe. With uncanny regularity, volley fire would flash unexpectedly from any direction, downing troops by the score and yet nothing of the enemy could be seen. Bushwhacking indeed! When Birney’s initial battle line began to crack with the collapse of the 63rd Pennsylvania, the 108th New York was instructed to plug the gap. Led by their colonel, Charles Powers, the New Yorkers advanced towards the plank road and took their stand, The right of the regiment stretched across the road “leaving the center and colors along the edge of the woods.” No one in the regiment could ever recall such a murderous fire or such a hazardous position for the men. Desperately, the firefight continued, often at distances less than one hundred yards. Sergeant Bailey recalled that it “was a perfect hail storm of bullets down that road” but the 108th began to give ground under the tremendous volume of rifle fire and the presence of a flanking column on the right. In the midst of the confusion, the flag bearers decided that it would be prudent to withdraw with the regiment. However, as they were leaving, Bailey took personal offence at the sight of the Rebels and their red flag advancing towards them, fifty yards away on the right so inexplicably, he rose up and just stood there waving “the old flag in defiance” while enemy gunfire pockmarked the ground around him. As the Federals withdrew, confusion began to spread exponentially up and down the line, yet Charles Powers attempted to maintain order within his regiment. When a distraught courier, probably carrying an order to retreat, approached the Colonel of the 108th New York and informed him “the enemy are pouring in on us from every direction – infantry, cavalry and artillery; the battle is lost”, Powers made no answer. The confused courier believing that the colonel had not heard or understood him, repeated the “day is lost”. Slowly, deliberately, Powers cleared his throat, wiped the dust from his walrus-like mustache and with a deadpan calmness inquired “Did you see any gunboats?” Whether the messenger got the joke or not was not recorded but, despite the cool demeanor of its colonel, the regiment was in trouble and began to get jittery. At this point, Powers noticed that the national colors were not with the regiment and then saw Bailey’s performance in front of the Confederates. Over the next few moments, he yelled at the color bearer to rejoin the regiment but his call could not be heard over the pandemonium. Finally, as he started back in frustration to get Bailey, a bullet ripped through his left shoulder, passed through the left lung and exited his back. Blood began to gurgle from the hole in his back as Powers collapsed gasping from shock. He was quickly taken to the rear. Command of the 108th was turned over to Lt. Col. Pierce, who was wounded in the right hand while attempting to rally the men but refused to leave the field.15

As the 108th moved back down the plank road, bullets continued to whiz thickly through the air around the men. Of the eighteen recruits brought to camp by Sergeant Crouch, all fell or were wounded in the Wilderness. Recruit John Bailey, the brother of the flag bearer was severely wounded and his brother Charles, after his defiant act with the flag was peppered with shots through the clothes and flag but only one hit home. At first, it felt like a tap on the shoulder, but he soon began to feel nauseous and decided to turn the flag over to fellow bearer Thomas Crouch so that he could move to the rear. James Dack of Co. H, standing beside Bailey, felt a slicing pain through his neck and immediately suspected the worst. Luckily, only his canteen had been shot off, the force of the bullet severed the canteen straps causing them to jerk violently on his neck. Less than a hundred yards from the point of his wounding, Bailey came across Dr. Wafer attending to a score of wounded from the 108th New York, among them, Chester Hutchinson of Company B. Just before the battle the private had a premonition of being badly wounded which he shared with mess mates. When the regiment fell back, Hutchinson “was struck in the left breast by a minnie (sic), passing through the back and part of the lung, tearing the ribs from the spine as it came out.” The surgeon did what he could to dress the wound, but believed it to be mortal so moved on to his other patients. Fortunately the doctor was mistaken since Hutchinson, though reported killed, survived his wound but never returned to action. As young Bailey waited for treatment, he was clearly impressed with the behavior of the Canadian doctor. He “never knew of another surgeon to be that near to the front during an engagement” and judged that Wafer “was of the right material.” Nearly every captain had been wounded. Sam Porter received his fourth wound of the war, “a very wholesome flesh wound above the knee disturbing no nerves and breaking no bones.” Literally, the Rochester men were covered with blood, either “their own or that of their wounded comrades.” Nearly all the wounded were taken off the field but some too badly hurt or dead were left. One of the latter was Charles B. Dickson of Company A, Francis Wafer’s medical orderly at Gettysburg. The retrograde movement continued and Bailey came across the wounded Powers, supine upon a stretcher and about to be taken to the field hospital. When he saw the young flag bearer, the colonel painfully raised himself on his elbows, looked intently and asked, “Bailey, are the colors safe?” When assured that they were, he lay back and closed his eyes.16

Once at the field hospital, George Vaughn took charge of his stricken commanding officer. After the colonel was stabilized, Vaughn informed him that Lt.Col. Tom Davis of the 12th New Jersey, a close personal friend of Powers, was also being treated nearby and wondered if the colonel felt well enough to see his friend. Davis was wounded at about the same time as Powers, just after the Confederate resistance stiffened. A Rebel artillery shell hit the tree directly beside Davis and he collapsed, apparently lifeless. Upon regaining consciousness, he realized that the fragments from the tree had “gouged his face, left knee, right foot and left arm.” His mouth and jaw were so swollen that he could hardly speak. Though unhurt by the shell directly, Davis was in no condition to continue so he retired to the hospital. Soon Vaughn arrived with Powers and informed Davis of the arrival of his friend. Crawling from his tent, Davis gingerly made his way towards the prostrate form of Charles Powers. He leaned over his friend and through his swollen, battered lips, he lisped “Hello Chilly!” Powers, though still in agony from his own wound, looked at Davis for a moment, then a smile broke through the pain and he jokingly replied, “Well I guess that will learn you to keep your mouth shut!” That was their last meeting. Powers was transported to Fredericksburg and out of the war, never again to lead the Rochester Regiment into battle and Davis returned to 12th New Jersey the next day, May 7, 1864.17

Soon Carroll’s entire Brigade was rapidly giving ground and running out of ammunition. As usual, the historian of the 14th Connecticut blamed the failure on the other regiments of the brigade who supposedly abandoned the Connecticut boys.18 But, despite the claims of the troops from the Nutmeg state, very little could have saved the line at this juncture of the battle. Shortly after 11.00 a.m., Lt. Col. Moxley Sorrel of Longstreet’s staff led four Confederate brigades in a flank attack on Hancock’s left which caught the Second Corps totally unaware. Sorrel’s force had used an abandoned railway cut as a conduit to reach the Union flank undetected from which they launched an attack on Frank’s and McAlister’s Brigades of Barlow’s and Mott’s Second Corps Divisions respectively. Union troops were taken completely by surprise and the rout was on. Like dominoes, the brigades began to fall from left to right. Carroll, however, quickly perceiving the danger “changed the front of my command so as to meet them and fought them for some twenty minutes but finding everything else was retiring in great confusion, being hard pressed and flanked myself” fell back to the rifle pits and breastworks on the Brock Road. Here the entire brigade, including the three regiments detached earlier, “formed in proper order” and awaited the inevitable onslaught but after a lull of twenty minutes, they were allowed to retire farther from the battle line in order to make coffee and rest.19

Still the quiet continued and still no attack on the works materialized. Union officers wondered, “What does the continuing silence mean? Certainly something mysterious has happened. Why do they lose the one chance to complete the victory?” Quite simply, the Confederate offensive had stalled since the Rebels had once more mistakenly shot another one of their general officers, this time Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, Lee’s Old War Horse and guiding genius behind the attack. In the confusion that followed the loss, the Federals were given a respite to reorganize their shattered units and to strengthen their fortifications along the Brock Road. Carroll’s Brigade was placed third in line behind Birney’s headquarters in order to act as a reserve to defend the security of the Brock Road. Early in the afternoon, Hancock, inspecting the line, came across the wounded Carroll, with his arm in the same sling from the day before. The Corps Commander, resplendent in his trademark white shirt, reined in beside the fiery red-haired colonel and asked “whom he wished to have assigned to command his brigade, to which Carroll replied with spirit that he had not yet left the field and proposed to command his own brigade himself.” Hancock’s response was not recorded but surely some colorful oath was uttered since he trusted Carroll and certainly admired his courage.20

When the Confederate attack finally occurred, around 4.15 p.m., the Union troops behind their field works “were ripe for revenge.” At first the assault seemed tentative, “not made with great spirit” as the attackers made little headway against the fortified Union line. However, momentum swung back to Kershaw’s forces when a significant section of the defensive breastworks caught fire and the “heat at times became intense and the smoke blown, backward over the entrenchments, not only concealed the enemy from view, but blinded and stifled” the Federal defenders, thus coercing them to abandon the flaming fieldworks. When Jenkins’ Confederate Brigade quickly took advantage of the opportunity “and planted their colors on the breastworks,” General Birney called on Carroll and his men to retake the Union works. In front of his brigade, sling and all, the plucky red-head “dashed on the run across the road, and coming to a ‘front’, charged forward encountering the exultant Confederates in the very moment of their triumph, and hurling them headforemost over the entrenchments” thereby stopping the final enemy effort on this part of the line. By late that evening of May 6, for all intents and purposes, the battle of the Wilderness was over for the Second Corps of Grant’s army.21

As usual, the cost in human life was prohibitive. The infantry of the Second Corps had 5081 casualties of which Gibbon’s Second Division took 1259 or almost 25% and Carroll’s Brigade took 559 or 44% of the losses in the Second Division. Just over 10% of Carroll’s losses were captured or missing, so the brigade suffered 501 actual combat casualties. Of the nine regiments in Carroll’s command, the 1st Delaware suffered the greatest loss at 99 men whereas the 8th Ohio had the least at 22 men. The 108th New York lost 52 men, 10 below the brigade average of 62. At the end of the battle, the regiment must have been in desperate condition since Sam Porter wrote to his father that “there are scarcely forty sound men left. Francis Wafer had no time to stop and count the losses since he spent most of May 7th cutting and patching the wounded of the 108th then was required to find ambulances to transport those who required them to Fredericksburg, the first stop on the way to Washington for the more seriously injured. Toward nightfall, having received orders to return to their regiments, the majority of the surgeons and their assistants rapidly packed up the medical equipment. No sooner had they left the vicinity and reached their units than Rebel cavalry, roaming freely in the rear, descended on the hospital, capturing the wounded as well as the skeleton staff of remaining surgeons and the ambulance train.22 However, by May 7th Grant had already lost thousands of men so the loss of a hospital was an insignificant setback in his plan for the destruction of the Army of Northern Virginia. Later that evening, when his army marched, Grant, unlike previous opponents of R.E.Lee, did not re-cross the Rapidan to lick his wounds, re-fit for months and complain about manpower as well as assign blame for the initial stalemate in the Wilderness. On the contrary, with the intention to side step around Lee, the diminutive westerner moved by the left flank, and set his eye on Spotsylvania Court House to the southeast. Also, unlike previous campaigns, Grant kept the Army of the Potomac in contact with Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia since some form of fighting occurred constantly, even when the armies attempted to maneuver. From his hospital bed in Fredericksburg, Sam Porter wrote his father that soldiering with Grant “has been one succession of battles” and there would be no let up in the immediate future. First Sergeant Fletcher Thrasher of Company F noticed the bone weary fatigue in the troops who “had been marching, fighting, building breastworks, fording creeks and rivers, without a moment’s rest and constantly under fire for eight days.” There would be no rest at Spotsylvania Court House where the fighting would escalate to unimaginable brutality as Lee and Grant once more brought their armies into a fatal embrace.23

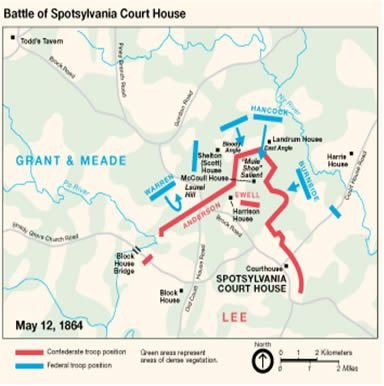

(Map taken from National Park Service website)

Grant’s plan was to secure Spotsylvania Court House before Lee could react, turn the right flank of the Confederate army and force Lee into a battle on Grant’s terms. So, while the Second Corps moved south to hold Todd’s Tavern and the intersection of Brock Road and Pamunkey Road thus covering the rear of the army, Grant swung his other two corps behind Hancock’s Corps southwards in the direction of Spotsylvania Court House. Burnside’s Ninth Corps was to approach the court house from the Fredericksburg Road, farther to the east. However the “attempt to seize Spotsylvania in advance of the Confederates failed through one of those misadventures which are frequent in war.”24This particular misadventure arose more from necessity than serendipity. Near dusk on May 7, Lee, who had deduced the objective of Grant’s movement, ordered Richard Heron Anderson, commanding Longstreet’s First Corps, to march south towards Spotsylvania at 3 a.m. the next morning. Waiting all night on the Wilderness battlefield held no attraction for Anderson and his men. The night was hideous. Brush and undergrowth continued to burn or smolder generating flames and smoke which obscured everything as well as irritated the lungs and stung the eyes. Cries or screams of the wounded combined with the smell of burnt flesh to transform the humid May night to one of gruesome horror. Understandably, Anderson started his march at 11.00 p.m. on May 7, four hours ahead of schedule and 2½ hours after the Federal Fifth Corps began its move to Spotsylvania. Not only did Grant have a head start but he had fewer miles to travel than the Rebels. Anderson, however, never slowed down and marched straight through the night whereas Warren’s Fifth Corps was constantly harassed and delayed by Stuart’s cavalry as it attempted to move down the Brock Road to Spotsylvania. By morning of the 8th, the 150 minutes difference had been made up as the divisions of Anderson’s Corps straddled the Brock Road, blocking Grant’s approach to the court house.25

After a slight diversion towards Lee’s left at the Po River, Carroll’s Brigade arrived near the vicinity of Laurel Hill on the afternoon of May 10, and took up position to the left rear of the stalled Fifth Corps, about 2 miles northeast of Spotsylvania Court House. Laurel Hill was not a hill but rather a ridge line, located about 150 yards south of the farm home of Sarah Spindle. Sarah’s house occupied a small rise to the front of Laurel Hill and the immediate surrounding ground, with the exception of the orchard, was open space. Generally the woods along the ridge, like the Wilderness, were “scrubby and dense rendering movement in line of battle difficult and observation over any considerable space impossible.”26 On Laurel Hill, the Confederates carved out their position from the dense woods, crowned it with earthworks bristling with artillery and cleared areas for open fields of fire for their infantry. By the afternoon of May 10, the rebel works at Laurel Hill extended from the intersection of the Old Court House Road with the Brock Road westward over the Spindle Farm where they were anchored on a small tributary of the Po River. Observing the position, Hancock noted that any approach to the enemy “was rendered more difficult and hazardous by a heavy growth of low cedar trees, most of them dead, whose long bayonet-like branches interlaced and pointing in all directions presented an almost impassable barrier” to a Union advance. Behind the natural cedar barrier, the extent and location of the Rebel fortifications was concealed so the Federals could only use the sound of gunfire to guess at the exact whereabouts and strength of the Southern forces.27 By the time Carroll’s men were ready to assault Laurel Hill, the Spindle House to the east of their position had been burned by a Rebel incendiary shell and a great deal of the cedar forest in their front was on fire, adding heat and suffocating smoke to aid the Confederate defense.28

As Carroll’s men prepared for the assault, the column was formed in three lines, each consisting of three regiments. While waiting at the edge of the cedar woods, some of the men watched the Rebel bullets whip up the sandy soil, “like a switch”. An officer, standing with his legs wide apart, watched fascinated as the soil seemed animated between his shoes. In the 108th New York, which formed the right of the third line, Lt. Col. Pierce felt slightly feverish as the hand wound from four days earlier had not received full medical attention and was probably infected. Only nine days had passed since his return to the regiment after suffering the horrendous facial wound at Morton’s Ford, three months earlier, which he could have parleyed into a permanent ticket to Rochester. But the war was in his blood so the full-bearded warrior and ex-schoolteacher kept coming back and, although he had lost the sight in his left eye, the word around camp was “he could see better and know more of what was going on with his one eye than he could when he had both.”29

At 4 p.m. Gibbon’s Second Corps Division combined with the divisions of the Fifth Corps for an all out attack against Laurel Hill. The brigades of Carroll and Webb formed roughly in the centre of Warren’s line with Fifth Corps troops on their right and left. Owen’s Brigade deployed behind Webb and Carroll as a support but was also positioned to exploit any possible breakthrough. Such optimistic forethought rapidly became a pipe dream. After charging “through a belt of burning woods 35 or 40 yards wide” Carroll’s men were subjected to “a concentrated and murderous fire” from the Rebel defenders. As they traversed the fiery woods, the integrity of the formation was destroyed and all three lines began to take casualties. Once out of the woods, the men had “to toil through the heavy clods in the ploughed field on the face of that terrifying hill.” For some the exertion was too much. Jacob Winslow, the young man who had the religious epiphany at Gettysburg that led him to God, “fell senseless to the ground” unhurt, but “completely worn out and exhausted.” Later in the summer, he would once more rejoin his regiment. Carroll claimed in his report that the right part of his line broke through the Rebel bulwark but if they did, an Ohioan asserted, “they never came back” since not “enough human beings could pass through the deadly storm of musket balls and canister to reach the crest of the hill or to do anything but surrender when they got there.” All along Carroll’s line men continued to fall in what was becoming an obviously futile attempt to storm the Rebel line. Thomas Crouch, the new color bearer for the 108th, was taken down by a leg wound. Sergeant Andrew Boyd of Company H was felled by a bullet in the right arm near the shoulder. All was smoke, noise and destruction. Some of the wounded fell in the woods and were lost to the encompassing flames. Frederick Frey of Company F, who had left the tip of his nose at Gettysburg, was hit in the chest and fell unconscious in the field. After a few minutes, he came to and realized that, luckily, he had wrapped his canvas tent and rubber blanket across his chest before the charge. He was hit directly over the heart but the ball had only managed to cut “through two or three thicknesses of the canvas so he was bruised and alive. Others were not so lucky. Sergeants Plunkett and Elwood, carrying the near lifeless body of Corporal William Lyons, headed back towards the starting point of the brigade. Although under constant fire, they managed to find a stretcher that had been abandoned. Since orders “had been issued not to permit any man to go to the rear with a wounded comrade”, they were soon stopped by an officer. Before the advance, these three men swore “to stand by each other” and to make sure they would not be left on the field of battle. The officer, perhaps conceding the futility of the assault, allowed the group to move rearward. Lyons was in agony as his two friends attempted to bring him off the field. At one point, he cried out “blessed Virgin Mary” but could not finish the prayer. Once through the woods to relative safety, the sergeants came across Dr. Wafer. Examining the wound in the chest and the exit wound in the back, along with condition of Lyons, the doctor saw no hope. Wafer looked up and said “Boys if you have anything to say to him, or he to you, do it quickly as he has but a few moments to live.” No sooner had the doctor spoken than Lyons simply gasped and died. His two friends searched the area for digging implements but found nothing. Finally, Ellwood broke apart his canteen to form a pair of crude scoops and began to dig a grave for Lyons. Plunkett joined in. Soon they lowered the still warm body of William Lyons into the grave, marked by a tree upon which they carved his name. The doctor moved on to other patients and the sergeants returned to the front in time for the second charge against Laurel Hill.30

After the failure of the initial charge, Carroll “fell back to the original position” near the inner edge of the cedar woods. The woods, once seen as an obstacle, now provided shelter for the men of the weary brigade lying on the ground awaiting orders. Waiting, however, provided no let up since they now received fire from an unexpected source. Loaded guns, dropped or discarded by the dead and wounded in the fiery fields, began to discharge as the flames reached them. Many of the abandoned weapons fired in the direction of Carroll’s men who, at the moment, required no further aggravation. At 6 p.m. the order came for a second assault designed to serve as “a diversion in favor of a VI Corps advance” against the Rebel centre, farther to the east. For this second effort three divisions of the Second Corps would attempt to do what Gibbon’s men and the majority of the Fifth Corps could not do an hour earlier. Such planning, or lack of it, stunned the troops. How many had to die or be sacrificed to prove that Laurel Hill could not be taken in such a manner? Luckily, Carroll’s men were relegated to the second line of the attack column. Once more, the assault disintegrated when the front line “no sooner began to emerge from the wood than they were met by so heavy a fusillade from the hill-tops as to be driven back in some disorder into the wood” where they remained for the rest of the 10th as well as the 11th of May. However, by nightfall of the 11th, Grant taking heed of Emory Upton’s temporary successful breakthrough on May 10, decided to emulate his young subordinate by using an entire corps for a swift dagger-like thrust to penetrate the centre of Lee’s line at Ewell’s infamous Mule Shoe salient. Predictably the job was assigned to Hancock’s Second Corps.31

Quite simply the salient formed in the centre of Lee’s line when the Confederate “line followed a low ridge that crossed the Brock Road and angled northeast toward the Landrum House. Before reaching the house, the line deflected sharply to the right toward Spotsylvania Court House resulting in a large bulge that the troops promptly dubbed the Muleshoe Salient.” Nearly half a mile wide on average and about one mile in depth, the convex or front end of the ‘shoe’ faced roughly north while the sides, facing west and east respectively, curved into and rejoined the regular line on each side of the bulge. Directly at the centre of the Mule Shoe stood the McCoull House and less than half a mile farther south, the Harrison House, headquarters for Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell. Tactically the salient was a liability since it could be attacked from three sides, none of which could support the other and because of its shape a concentrated fire could not be achieved. The normal line on each side of the bulge could offer support but had to be careful not to fire on the men occupying the salient. Ten months earlier Sickles’salient at Gettysburg almost cost Meade the battle and to Robert E. Lee the engineer this bulge in his line at Spotsylvania was an annoyance at least or a defensive nightmare at worst. That it turned out to be the latter was a combination of Grant’s luck and Lee’s error.32

At 4 p.m. on May 11th, Hancock, whose corps was the right flank of the army, “received orders to move Birney’s and Barlow’s divisions at dark to a point near Mott’s Division on the left of the Sixth Corps, thereby becoming the left of the Army of the Potomac. In essence Grant rotated the axis of his army; the right – Second Corps – became the left; the centre – Fifth Corp – became the right and the left – Sixth Corps – became the centre. Burnside’s Ninth Corps, still functioning as almost a separate unit, was the extreme left of the Federal force as it moved on the Fredericksburg Road toward Spotsylvania.33 An unexpected result from all this maneuvering and lack of offense on Grant’s part was that Lee became confused about his opponent’s purpose. During the afternoon of May 11th, a number of the Confederate high command was gathered at the Harrison House in order to assess and interpret the overall situation on the field. As the afternoon wore on, with no Federal offensive and reports that Union artillery and trains were apparently vacating the front, Lee gradually believed that the Federals “were retiring towards Fredericksburg” and therefore vulnerable to a Confederate counterattack on a selected portion of the army, one of Lee’s specialties. To ensure that Confederate pursuit would be swift and efficient, Lee ordered Ewell to begin “to withdraw the troops from the trenches” in the Muleshoe and for Armistead Long “to do the same” with the artillery. Based on his own mistaken assumption, Lee weakened the very area where Grant intended to attack with the entire Second Corps.34

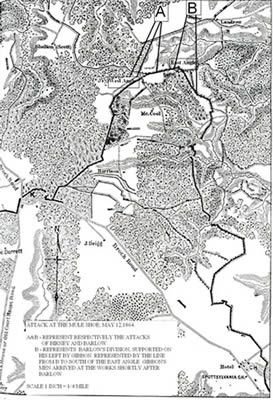

Attack at the Mule Shoe

(map adapted from V.D.Brown – see Bib. for full citation)

Before dark on May 11th, a thundershower temporarily refreshed the men of the 108th New York still holding onto the inner edge of the cedar wood. Thick, eye-burning smoke wafted from the fires in their front and as darkness settled, the landscape resembled a murky waste land where lost and dying souls cried out with pain and fear. The rain did not pass but instead started to drizzle intermittently then picked up in intensity as the night passed. Shortly after 11p.m. Gibbon’s troops, the last of the Second Corps divisions, followed the others to the left of the army. Word came down the line to make no noise. Tin canteens and cooking utensils were to be smothered in order to maintain the silence. Lt. Col. Pierce, now visually hampered by his sightless left eye, asked Sergeant Ellwood to guide him on the march since the rain and darkness clouded his vision. Through woods, swamplands and fields, over fences and ditches, the sergeant guided the lieutenant colonel. In a silence made ominous by the night and anticipation of what lay ahead, each was alone with his thoughts as were most of the men of the regiment as they slogged through the dreary night. Heavy rain poured “down in torrents and the air was thick with mist and fog from the soaking earth.” Uniforms, sopping with water, hung heavy on the men, while movement through the deep and slippery mud soon exhausted even the fittest. A Massachusetts soldier summed up the experience as a “more dismal night march was never known.” Soldiers of the 108th New York trudged along with full ammunition packs and empty growling stomachs. Rain overhead, mud beneath, hearts heavy but filled with hope, the New Yorkers crowded along “keeping as close together as the nature of the ground would admit.”35

After midnight, The Second Corps began to arrive in the area of the Brown House, located about ¾ of a mile to the northwest of the Landrum House which marked the approximate centre of the Confederate picket line around the salient. Because of earlier fighting the grounds around the Brown House were already entrenched as the lead divisions of Birney and Barlow “passed quickly over the intrenchments” and moved south “as near to the picket line as possible.” Barlow formed the Union left and Birney the right. Gibbon’s troops arrived later and Carroll’s men marched “until dawn” when they halted behind the works, near the Brown building. Gibbon’s Division was to support Barlow while the fourth Second Corps division, under Gresham Mott, was to support Birney in the proposed morning assault on the east and west faces of the Mule Shoe respectively. These generalized instructions seemed to be the extent of the planning. Plans to reconnoiter the Confederate position were aborted and although Mott had been there since the 10th of May he still had no idea of the topography of the ground in front of the salient. At this point, the impatient, frustrated Barlow, whose youthful appearance reminded a staff officer of “a highly independent mounted newsboy” and whose outspoken intolerance for stupidity was already legendary, concluded that the charge was a forlorn hope “and placed his valuables in the hands of a friend.” 36 Nevertheless, despite his gloomy forecast Barlow, over the ensuing hours before dawn, gathered some rudimentary information as to the general configuration of the Rebel works and the comforting news that the ground over which his division would pass was reasonably clear. He shared this information with his fellow division commanders who, in turn, filtered it down to the brigades. Finally, so that everyone in the morning would know where to go, the direction of the advance “was ascertained by a line determined by a compass on the map from the Brown house toward a large white house [the McCoull House] known to be inside the enemy’s works, near the point we wished to strike.” All that was needed now was daylight and for Grant’s luck to hold.37

At 4.35 a.m. on May 12, after a half hour delay due to fog and darkness, Birney’s and Barlow’s divisions lurched forward and gathered momentum. A few minutes before the charge began, Hancock ordered Carroll from his reserve position to go in on Barlow’s left flank and assault the Confederate works. Ever ready for a fight, Sprig Carroll moved his brigade out at the double quick in order to catch up with the attack column. Rain continued to fall and, almost inaudibly, word to fix bayonets passed through the regiments as they moved silently through the foggy dankness and grey darkness of a morning reluctant to shed light. When the column spread out, the men seemed to be swallowed up in the fog and parts of the line were no longer visible. Some of the men could hardly believe that “an assault was under way” in such conditions. Picket fire into the flank of Barlow’s Division from Rebel riflemen located at the Landrum House could be heard but not seen. Two regiments from Carroll’s Brigade, the 8th Ohio and 1st Delaware, both under the command Colonel Franklin Sawyer, peeled off and overran the Southern marksmen who disappeared “after a sharp volley or two.” With this accomplished the 108th New York and the remainder of the brigade caught up with Barlow’s left flank and pitched into the attack on the eastern face of the Mule Shoe. The assault column was heavy and compact, in some places 20 men deep, and rolled forward like a battering ram, trampling and driving all that got in its way38. About three hundred yards from the Mule Shoe, someone in the ranks gave out a boisterous cheer which was soon picked up by the Irish Brigade and then spread throughout the entire force. Already the lines were collapsing on each other and by the time they reached the Rebel works, the Union forces were becoming one large disorderly mass of men. Both divisions hit the salient at approximately the same time and carried “the line at all parts in a few moments, although it was desperately defended.” Birney’s force smashed Walker’s Stonewall Brigade while Barlow’s men overran the remaining brigades of Major General Edward Johnson, who was captured while attempting to stop the Federal flood by striking at them with his cane “as they leaped over the works.” Carroll’s and Owen’s brigades arrived just after Barlow but a bit farther to the left where they broke up the brigade of George Hume Steuart, also capturing its commanding officer. Lee’s Mule Shoe, “a wretchedly defective line” line to begin with, began to disintegrate as the Union troops literally pushed their way into the Confederate fortifications.39

At first, a member of the 108th New York thought that they had caught the Rebels “napping” but resistance developed and there were nasty firefights as the Confederates regained their composure. Sergeant David Riggs, color sergeant of the 1st Delaware, bragged that he would plant his flag “on the rebel breastworks or die in the attempt.” As he approached the crest of the slope at the Mule Shoe, he was killed instantly but his flag was carried by another into the works. When the Rochester Regiment emerged from the woods on the Confederate front they broke through the abatis, “climbed the breastworks and jumped down on the astonished enemy.” Once inside, Sgt. Fletcher Thrasher recalled the formidable nature of the fortifications:

The works on the line of battle were three to four feet thick and about five feet high, with a heavy log on top to protect the head and raised high enough to get rifles through and get a good view of the approaching enemy. In addition to this was a line of abatis or sharp pointed sticks driven into the ground with the dirt filled in around to make them firm, being elevated in front at an angle of about forty five degrees and placed a foot apart.

In the end, despite the nature of the works, the Union force was too large and a significant number of Johnson’s troops were captured or surrendered. One Confederate shot a Union officer at point blank range “almost within touch of his musket, then threw down his piece and called out ‘I surrender’.” A nearby Federal, enraged by the Rebel’s act, shot him dead. Another Confederate “crawled out from under a tent fly” and when ordered to surrender told his captors “with great nonchalance” to relax “don’t get so excited. Just let us get our coats on and we will go to the rear.” Not all Rebel captives were so obliging. Brig. Gen. Steuart was livid about his captivity and “insulted everybody who came near him. He “was rewarded by being sent on foot to Fredericksburg where there was plenty of mud and one stream up to his waist.” Perhaps one of the more enterprising Rebels surrendered to Owen’s Philadelphia Brigade. After the brigade crossed the works, a Confederate veteran rushed towards one of the officers of the Pennsylvania unit but was shot as he approached. He fell a few feet in front of the Federal and as he lay there said “I am sorry you shot me; I was coming to take the Oath of allegiance.” The Union officer, perhaps responding to the Rebel’s sense of humor or sheer temerity, informed him that he had no copy of the document but wondered would some whisky alleviate the southerner’s disappointed desire to re-join the Union. “That will do as well” replied the prospective convert.40

Once the line was broken, and with such relative ease, the men “became insane with the excitement of victory.” All order was lost. All the marches, all the deaths, the blood, the weariness, the horror of the previous seven days, the fruitless failures, all erupted in a cathartic release as the object of their three years of frustration, Lee’s army, seemed smashed and in flight. Now the end of the war could be seen. Some men fell to looting the Rebel camps, but in general, the mass of men continued forward, deeper into the Mule Shoe. Control could not be exerted since most of the officers were on foot and could not be seen or heard. Barlow’s men, in squads or as individuals, continued the charge through the wooded area behind the east angle until they passed the McCoull House and saw a second line of partially completed fortifications across the rear or open end of the Mule Shoe. This was Lee’s last line of defense which he had ordered to be constructed on May 11th and “to which he proposed to move back the troops occupying the angle.” Now he needed time to hold what was left of the salient in order to finish the second line and save his army. He would counterattack and push the Federals back.41

Incredibly, the battle was only one half hour old and fifteen minutes after the breakthrough Lee began to counterpunch with the brigades from John B. Gordon’s Division that had been in reserve behind the unfinished line at the base of the Mule Shoe. To stabilize the east angle, Lee dispatched two brigades, Hoffmann’s (formerly Pegram’s) Virginia Brigade and the brigade of Clement Evans (formerly Gordon’s Georgians), to meet Barlow’s and Gibbon’s Federals as they emerged from the woods surrounding the McCoull House. Lt. Col. Thomas H. Davis, who six days earlier lay in the field hospital beside his friend, Charles Powers of the 108th New York, led his 12th New Jersey across the field in front of the house in a wild charge on the second line of works. Agile and animated, the colonel appeared unaffected by the painful bruises from the earlier wound. His slouch hat blew off, “carried away by the wind” and his Old Testament length beard streamed over his shoulders. Like a dervish, his saber twirled in the air above his head and as he drew his revolver and exhorted his men forward towards the enemy, the movement suddenly stopped. His head snapped back as the bullet tore through his neck and falling backwards, “almost touching” the regimental colors, Colonel Davis died. The charge of the 12th New Jersey was over as it was over all along the line, once the Confederates rallied.42

Although outnumbered, the advantage lay with the Rebels since they were organized and under control of their officers. Disorder still prevailed on the Union side. Officers looked for commands while enlisted men began to gather around color bearers in an attempt to find some organization. At the double quick, Gordon’s troops advanced “with great vigor” against the left of Hancock’s column, driving the disordered mob some distance back toward the east angle where the Federals began to furiously dig ditches on the other side of the parapet in order to ‘turn’ or reverse the fortifications so they might defend them. At first, Hancock had planned to use his reserve divisions, Mott’s and Gibbon’s, to turn the captured works once the initial breakthrough occurred, but the majority of these men, caught up in the excitement, continued with the charge into the Mule Shoe. During the scramble backwards to the safety of the outer works, James Loughlin, the second color bearer for the 108th in as many days, fell when hit in the chest by a spent bullet that did not penetrate but knocked him off his feet before he reached the breastworks. For a moment the colors of the New York regiment seemed lost since the Confederates were hot behind them. Sgt. James Westcott and James Plunkett went back for the colors and Loughlin. Bullets nicked the earth and kicked up dust all around them but they succeeded. Westcott helped the color bearer to the rear while Plunkett took the flag and planted it on the breastworks in “defiance to the whole rebel army.” By 8.00 a.m., for a distance of about a mile, the Rebels forced the “wearied and disorganized” Federals “to the outer face of the captured line, around which was waged until three o’clock the following morning, the fiercest battle of modern times.”43

For both armies this was the seventh straight day that they had been at each others throats but nothing so far would compare to the horror generated during the next 20 hours around the Mule Shoe. There were two prominent angles in the salient, the West Angle which would become known as Bloody Angle and the East Angle at the northernmost top of the Mule Shoe, about 300 yards east of its counterpart. Just to the south of the East Angle, Carroll’s and Owen’s men withstood the determined Confederate assaults intended to re-take the Mule Shoe or, at least, hold the Federals at bay while Lee finished his second line of entrenchments across the base of the salient. At the East Angle the fight may not have been so extreme as at Bloody Angle but over the narrow parapet the men of the 108th New York and the Virginians from Hoffmann’s Brigade literally traded blows for the next six hours, “actually resting their rifles crossed on the same low breastwork – pouring their fire in until all fell dead or wounded and were immediately replaced by others who fell upon the bodies of their comrades until the trench was for some extent piled” deep with bodies. Charge and countercharge, masses of men surging forward like a wave, then falling back in a tidal rhythm. Participants shot each other at such short range that their uniforms were set afire. “Men fired into each others’ faces, were shot through the crevices of the logs, bayoneted over the top of the works.” Exhausted men of the 108th sat down in the muddy trench, hastily excavated by their comrades and, in a somnambulistic haze, mindlessly loaded rifles for the Rochester men who climbed to the top of the works and fired into the Rebel mass. Rifle after rifle was passed up until the shooters either fell into the enemy or backwards to their friends. All the while rain fell relentlessly, soaking the living, the dying and the dead, mixing blood with water that trickled quickly down the slope of the trenches and pooled on each side of the works. Wounded men “dragged themselves about drinking out of the pools and hollows.” Some, too badly disabled, could only “lay with open mouths to cool their parched tongues by catching the few drops as they fell.” To the north of the angle, there was a sink-hole in which “rain and blood collected until it was full of red water, and around this a hundred wounded men were drinking and groaning.” Some died from wounds, others drowned when they fell wounded and helpless in the breastworks and were trampled into the water and mud by foe and friend alike. Quite rightly, a member of the 108th New York declared the “angels of death danced over this fated spot till they had become weary of their victories.”44

As the morning hours wore on, there were odd occurrences of feigned or mistaken truces. On one occasion, a large number of Rebels “made signs of surrendering, waving handkerchiefs on their rammers.” The Union men “ceased firing and called to them to come over” which the Rebels appeared ready to do. Suddenly, a second line of Confederates came up “from the other side” and “rushed for the works” hoping to catch the Federals off guard. Such was not the case and the blood-letting began again. Near the west Angle, Colonel Joseph N. Brown, commanding McGowan’s South Carolina Brigade, related that at one point he thought the Federals wished to surrender. He called for them “to lay down their arms and come in.” On the other side, the Union officer claimed that the Confederates had raised the white flag. A conference was arranged to clear up the confusion. Apparently no one was surrendering so the Federal officer made his way back to the line. He was shot in the back, midway across the field since he failed “to exhibit his flag of truce”. Even if the officer believed that the informal conference guaranteed his safe return, on a stage such as this what did the murder of one more Federal mean? In the third year of the war, chivalry was now a needless luxury so the “firing again commenced with unabated fury.”45

Incongruously, in the midst of the madness within the “sulphourous canopy” that shrouded the east Angle, a young woman appeared on the battlefield. Just after a particularly nerve wracking assault of “musket balls, shrapnel, and every sort of projectile”, a sergeant in the 8th Ohio clung fiercely to the outer works and could not believe his eyes or ears when he saw her. All the regiments were still mixed, and short lulls in the action allowed troops to seek their own regiments. As the sergeant searched the crowd for a recognizable face, he heard a man calling to a woman to “come this way.” “To hear a woman’s name at such a time was rather startling” admitted the Ohioan but as he looked around, sure “enough, there was a woman!” Sun burnt, square featured, about twenty five years old, her name was Marie Tepe, vivandiere of the 114th Pennsylvania or Collis’ Zouaves. She was with the men of her regiment and the sergeant watched her with interest as she moved along the trench with mud spattering her red trousers and dark blue overskirt. She moved without anxiety, her gay laugh cutting through the oppressive atmosphere of carnage, making the war seem trivial and filling the sergeant with admiration. When the magic of the strange moment passed, he gruffly concluded that she “was either wonderfully courageous or else she did not understand the danger.”46

Into the afternoon hours of May12, the fighting was almost continuous up and down the line of the East Angle. Shortly before Carroll’s men were withdrawn, around 3.00 p.m., the Virginia troops launched a final assault and broke into the works defended by the 14th Connecticut. A nasty encounter with bayonets ensued. Men of the 14th were pierced “through the head or in the side with rebel bayonets.” In one macabre scenario, a Connecticut soldier “thrust his bayonet through the breast of a Confederate” who simultaneously thrust his bayonet into the neck of the Fourteenth man.” Both men “stood against the breastworks, the guns of each serving to brace them and hold them in this standing position.” On the front of the Rochester Regiment the noise “was deafening and clouds of smoke “rolled up to the very heavens.” Men of the 108th “looked like so many demons – dark eyes piercing out of the sockets, smutty faces, clothes tattered and torn, stomachs lean and gaunt and tearing so many cartridges with their teeth that the taste of powder had made them frantic.” Peter Oliver of Company B, a young railroad worker before the war, was not quite frantic but the taste of the black powder in his mouth was revolting. Crouching cautiously to reload behind the shallow embankment, he then stood upright to fire but before he could squeeze off the round, a Rebel shot hit him between the wrist and the elbow of his left arm, breaking the arm and “shattering the bone.” His arm collapsed rubber-like to his side, his gun fell to his feet. Gingerly, he raised the wounded limb to his chest, holding it there for a few moments until his company sergeant, bearing the Shakespearean appellation of Hamlet Richardson, ordered him to the rear. Just as he turned to go another bullet struck the wounded arm, this time “taking the cap off the elbow right away.” Oliver crumpled to the ground, but quickly regained his feet since an immobile target usually got riddled. The fury of the Confederate assault began to dissipate and young Oliver moved rearwards. Keeping the arm immobilized was a painful and difficult task, but soon Oliver managed to overtake the ambulance corps near the Landrum House where he met his company mate, Vincent P.Kelly, wounded in the right leg two days earlier at Laurel Hill. Kelly’s wound had not been attended so his attempt to catch up with the ambulances was frustrating until Oliver offered his good shoulder for support and the he managed to hop along until “he was assisted into the wagon.” Arrival at the field hospital brought little relief. Wafer was so overworked by the constant parade of broken bodies that Kelly and Oliver had to wait their turn. A group of wounded “lying in the shade cast by some large oak trees” had obviously been designated as hopeless. The pallor of death slowly worked its way into their grim grey faces. As soldiers and artillery passed, these men said nothing but simply watched with a mild detached disinterest. “One wounded man, a blond giant of about forty years, was smoking a short briar-wood pipe” which he gripped firmly by the stem. A passer-by inquired what he was doing. Slowly, carefully, the soldier removed the pipe from his mouth and replied “Having my last smoke, young fellow” then just as carefully put the pipe back in place. He tried to smile but he knew death was close by and the taste of that last good pipe should not be wasted in conversation. Near the pipe smoker another of these “wounded men was trying to read a letter.” Either he was too weak to hold the letter or the pall of death was clouding his sight so he “thrust it unread into the breast pocket of his blouse and lay back with a moan.” Farther down the line, lay some wounded from the 8th Ohio. One man, an Irishman named Quinn, soaked by the rain, had been shot in the intestines “which protruded through the wound.” The surgeon pushed the bowels back into the abdomen, “set a handful of lint against the big hole and tied a bandage around his body.” Later that afternoon, Quinn died, as did all the others in the group. Wafer took Kelly in first, amputated his right leg, then took Peter Oliver and amputated his left arm. Next morning, both men were sent to Fredericksburg where they lay on the brick floor of a church for three days. Those “who had two legs would get water for those who had one leg and those who had two hands dressed the wounds for those who only had one hand.”47

Shortly after three o’clock, Carroll’s Brigade was withdrawn, as were the other brigades in Gibbon’s and Barlow’s Divisions, to Federal entrenchments facing the East Angle, at about 300 yards distance. However, the fight at the West Angle seemed to gather intensity as Wright’s Sixth Corps fought alongside Birney. Both Barlow’s and Birney’s thrusts through the salient and deep into the Mule Shoe had been pushed back to the outer fortifications. At the West Angle, which Grant and Lee realized was the key, the armies fought until exhaustion. Finally in the early hours of May 13, Lee withdrew his men back to the second line of works created across the base of the Mule Shoe, leaving the empty salient in Federal hands. Grant may have gained some real estate but Lee’s army, though somewhat diminished, still stood on his front, safely behind a proper line of fortifications. He had the chance to break the Grey Fox’s army in half on the 12th of May but failed to do it. A soldier of the 10th New York, the National Zouaves, was in Carroll’s front line and wondered:

Had the brigades which first struck the enemy halted after the capture of the works, and reformed their regiments before advancing further, possibly the Rebel army might have been effectively broken, turned and routed by the wedge-like charge of Hancock’s troops; but the precipitant rush after the flying enemy broke the formation, and the Rebels rallied on their advancing reserves.

Hancock’s thrust had been too successful too quickly, had penetrated too deeply without first widening and holding the breech, and thus was pinched off when Lee’s organized units attacked the disorganized mass of Federals. To compound matters, Burnside’s action against Early’s Third Corps, southeast of the salient, did not effect a breakthrough to exploit further the disorder caused by Hancock so Lee could concentrate on restraining Hancock and Wright while he cobbled together a new line. In a letter to his wife, Theodore Lyman, Meade’s aide, once described Grant as a man who “habitually wears an expression as if he had determined to drive his head through a brick wall, and was about to do it.” Five days later, on the 18th of May, Grant once more decided to ram his head into Lee’s new line at the base of the Mule Shoe. With Hancock’s Corps in the middle, theoretically supported on the left by Burnside’s Ninth Corps and on the right by the Sixth Corps, the attack simply resulted in more Second Corps deaths. Neither “Wright nor Burnside did much more than was necessary to disclose the enemy’s real line and ascertain that it was of a formidable character.” Same troops, same procedure and therefore same results.48

Luckily, the 108th New York got to be observers for this latest effort at the Mule Shoe. Their regiment and brigade were now under new commanders. Lt. Col. Pierce, still suffering from his untreated hand wound of May 6, was told by Dr. Wafer after the assault of May 12 that his hand was infected and needed treatment or he would lose his arm. Pierce was in a Washington hospital by May 17th and the command of the regiment fell to the senior captain, Joseph Deverell of Company K.49 On the 13th of May, the same day that Pierce left command, Col Samuel S. Carroll was wounded again while leading Owen’s Brigade on a reconnaissance to determine the strength of Lee’s new line. Apparently, Carroll was “riding from the field to go to the hospital, the wound which he received in the Wilderness having become aggravated,” when he was asked by Gibbon to perform the duty. Despite the pain in his right arm and the accompanying fever, Carroll typically turned his horse “and placed himself at the head of his new brigade.” Upon moving closer to the enemy position, he was shot, this time in the left arm “through the elbow joint” and “knocking his elbow all to pieces.” Wafer recalled the colonel was such a fighter that, while they performed the bone resection, Carroll, under chloroform, was still on the field of battle and “never ceased to rally and encourage his men.” This wound permanently disabled the red headed colonel who Grant quickly appointed to the rank of Brigadier General for his outstanding work on May 12 and 13. At a time when true leaders were dearly needed, the man known affectionately to his men as “Old Bricktop” would not lead troops again in active combat. To take his place at the head of the Third Brigade Colonel Thomas Alfred Smyth, originally of the 1st Delaware and the brigade commander at Gettysburg, returned on May 17th, 1864. Smyth had become redundant in the Irish Brigade with the return of the senior colonel, Richard Byrnes of the 28th Massachusetts, so the loss of Carroll allowed Gibbon to transfer Smyth, a more than competent replacement.50

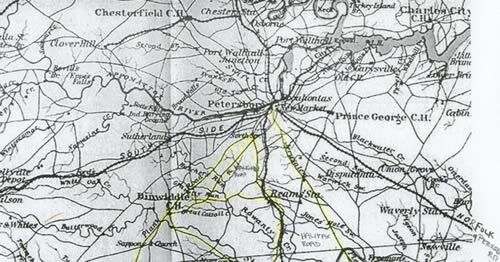

After Spotsylvania, Grant once more moved by the left flank, but this time with a slight difference. The Second Corps was dangled as bait on the left, with the hope that Lee would come out from behind his fortifications and attack the isolated corps. Humphreys explained that “upon the first indication” of a Confederate attack “the rest of the army following the corps might be able to attack before Lee could intrench. If Lee did not make the attempt on the isolated corps, then the movement would become simply a turning or flank operation.” Of course, Grant premised the operation on Lee’s natural aggressiveness and his inability to resist the attack in detail. Lee may have been aggressive but he was not stupid. He saw the plan for the crude trap that it was and did not bite. Instead Lee set his own trap at the North Anna River which Grant fell into and only narrowly escaped. During all the maneuvering and continuous skirmishing around the North Anna, the 108th New York was not heavily involved, losing only 5 wounded from May 22 to June 1.In fact, the entire brigade for the same period recorded a loss of only 73 men but all that was about to change. Lee’s lethargic performance and lack of aggression at the North Anna stemmed from his physical illness and his lack of trusted subordinates to carry out his plans. But inadvertently, the Rebel chieftain’s behaviour led his opponent into thinking that “Lee’s army is really whipped” since the “prisoners we now take show it and the action of his army shows it unmistakably.” After the stalemate at the North Anna, Grant acted on this belief and again moved by the left flank around Lee’s right. To the southeast, the North Anna River joined with the South Anna to become the Pamunkey River and on May 27th Grant started his move down the eastern bank of the Pamunkey, bringing him ever closer to Richmond and yet another confrontation with Lee at a dreary crossroads called Cold Harbor.51

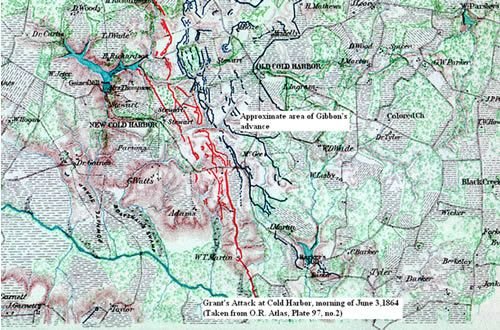

Grant’s attack on June 3,1864 at Cold Harbor represented the culmination of the first phase of the Overland Campaign. Despite defeats at Haw’s Shop and Bethesda Church, Lee’s army was still in tact and, by the third day of June, entrenched on a formidable line anchored to the south on the Chickahomony in the area of Turkey Hill and sprawled north eastward to the Shady Grove Church Road. Facing Lee, from north to south, were Burnside’s Ninth, Warren’s Fifth, both anchoring the Federal right in the Bethesda Church area, followed by Smith’s Eighteenth Corps, the latest addition to Grant’s army, in the middle, then Wright’s Sixth Corps and Hancock’s Second south of Cold Harbor Road and anchoring the Union left. On this first Friday of June, Grant still labored under the misconception that the Army of Northern Virginia was in its death throes and decided to launch an attack along the entire line, “some seven miles or more in length, hit or miss.” 52 His decision to assault Lee’s army at Cold Harbor has generated, perhaps, as much debate as Lee’s decision to send Pickett and Pettigrew charging across the Emmitsburg Road on July 3, 1863. Both were calculated risks which could reap enormous benefits if they paid off and, ironically, while both attempts failed, after the war, one general was canonized and the other was dehumanized into “Butcher” Grant. In support of Grant, his aide felt that the general “considered the question not only from a military standpoint, but he took a broader view of the situation.” To carry on the war the cost was $4,000,000 a day and the northern people “were becoming discouraged at the prolongation of the contest.” To move south of the James River, without fighting Lee would alienate the people, but more significantly, Grant felt that he could end the war at this point and “there was at present too much at stake to admit of further loss of time.” Finally, as at Antietam, Lee’s army was backed onto a waterway, this time the Chickahominy, and if line broke, the Rebel army would have nowhere to go. Consequently, Grant should be given the benefit of the doubt in that he believed the attack could have succeeded and was worth the risk to end the war. However, as a modern historian has pointed out, the handling of the details and tactics of the attack left a great deal to be desired.53

Grant's attack on Cold Harbor, June 3, 1864

(Map taken from O.R. Atlas plate 97, no.2)

To start with, Grant put Meade in charge of all the details for the attack. No two soldiers could have been more fundamentally different: Meade, the aristocratic Philadelphian, a child of the Army of the Potomac, born to caution, the hero of Gettysburg, who as Lee stated “would commit no blunder” but who also would take no risks ; then Grant, the westerner, the outsider, the risk taker who cut off his supply line to cross the Mississippi, fought between the armies of Johnston and Pemberton, defeating both of them to capture Vicksburg, rescued Chattanooga, broke Bragg at Missionary Ridge and, most importantly, was not afraid to fail since he had known failure for most of his adult life. So when faced with planning the details for a risky frontal assault, Meade emulated Pontius Pilate and washed his hands of the whole affair and left the planning to the corps commanders who did little in the way of reconnaissance for Rebel dispositions and topographical details of the field. Compounding his initial error was Grant’s order for a grand or general attack along the entire line which would require a full cooperation between all the corps – a requirement that Meade had already scuttled. Also, such coordination had yet to be achieved during the entire campaign, why would this time be any different? Francis Walker, the adjutant of the Second Corps, found fault with the plan and asserted that since the Rebel army was securely in position on June 3, then the general assault would not exactly be a surprise. Furthermore, he suggested that had “the 3d or the 4th been utilized for a reconnaissance” conducted by “the engineers and the fighting staff” to determine some weak point in Lee’s line “upon which an attack could be delivered with a reasonable chance of success.” At such a point “at least six divisions” could be concentrated “to take advantage of any opening that might be made.” Although Walker’s plan seems to be a bigger and better coordinated repeat of the attack on the Mule Shoe, did he really think that Lee would be fooled again and that Lee would conveniently remove troops from the attack area? Tactically Walker’s comments are sound but, typical of a number of critics, Walker had the advantage of hindsight when he penned his words, an advantage not available to Grant on June 3, 1864.54

For the third time in 21 days, the Second Corps was expected to march to and attack a fortified line. On the night of June 1, Hancock received orders to bring his men to Cold Harbor before daybreak of June 2 and form on the left of Wright, south of Old Cold Harbor along Dispatch Station Road, thereby becoming the left of Grant’s army. Although night had fallen when the troops moved out, the heat from the day had hardly dissipated, the thick air seemed close and cloying. Ankle deep dust stuck to their uniforms and caked the mouth and nostrils with a fine wet powder that made normal breathing an impossibility. To make matters worse, one division got lost. Meade sent out a guide, Captain William H. Paine, to expedite the arrival of the column but, at one point, the officer’s ‘short cut’ through a wood became narrower and narrower until the artillery got stuck “between the trees and was obliged to turn back” which in the muggy darkness only resulted in “much confusion.” Since troops became mixed “to a degree which made it difficult to straighten them out again”, the upshot was that the Second Corps did not arrive at Cold Harbor “till between six and seven o’clock of the 2d of June” and “in an exhausted condition.” Straggling was rampant. Some men marched 15 miles to cover 9 miles – a distance at night, a staffer remarked, which would “equal 25 miles by day.” Upon learning of the mishaps and the condition of the men, the proposed attack on the morning of June 2 was moved back twelve hours to 5 p.m. then backed up again to 4 a.m the following morning. Near 5 p.m., the sultry heat was broken by a thunderstorm that brought “great comfort to the men and animals”, while wiping the air clean of the dense dust clouds created by the movement of troops and wagons. On and off all night the rain continued and was replaced in the early morning by swirling fog which obscured vision and covered the killing grounds with a strange ethereal mist – a morning not unlike that of twenty two days earlier at the Mule Shoe.55