Chapter Two

Rochester's Forgotten Regiment:

The 108th New York In The Civil War

By Terence G. Crooks

Chapter Two:

Baptism Of Burnt Powder

In the cool morning hours of the first Sabbath in September of 1862, the 108th New York began its inaugural march to Rockville, Maryland. As the regiment crossed the Potomac River on the old Aqueduct Bridge, the Three Sisters to the west were barely visible through the mist on the river and the water fowl on Mason’s Island to the east were animated by the steady tramp of the troops on the bridge. The boys from Rochester moved through the quiet borough of Georgetown then took the Rockville Road.1 Of the eighteen miles to Rockville, the first four were "accomplished with comparative ease" but as the heat of the day began to rise, as well as the volume of dust, the men of the 108th bantered with each other about who would survive the march.Tom Yale, the thirty-five year old Captain of Company ‘G’, confidently predicted that George Washburn, the future historian of the 108th , "would be among the first to wilt " but Washburn stayed the course to disprove the belief "that the city men would first give out." However, as the hot march lengthened and the weight of "the heavily laden knapsacks and haversacks with accouterments, began to tell" the "wilting commenced." Discipline and self-control could not contend with heat and thirst. Whenever water appeared, "there would be a general stampede in spite of the officers. Notwithstanding all the caution given, the men would drink inordinately. They seemed like so many sponges and about as thoughtless." As the day wore on, the rear guard and stragglers soon outnumbered the marchers. Finally, late in the afternoon, the "sorry looking" New Yorkers limped into the Fairgrounds at Rockville to bivouac on the shady well watered ground while the Colonel reported to General Sumner. Colonel Palmer found Sumner at his Head-Quarters, a country home two miles from Rockville, and, as he had with Whipple, asked for clarification of the regiment’s status. Was the assignment temporary or permanent? Sumner seemed to miss the question and replied "You will report to General William H. French whose Head Quarters are about three miles to the right." When Palmer

pushed again for clarification, the sixty-five year old Sunmer " evaded any direct reply simply by remarking that General French’s Division would be mainly new troops for instruction " and that Palmer should " report to him."2

The Second Brigade of French’s Division, to which the 108th New York was assigned, could be termed a rookie brigade since all three of the regiments in the unit had been mustered into service less than a month before. Like the 108th New York, the 14th Connecticut had been formed in late August and the other regiment, the 130th Pennsylvania, could claim seniority since it was mustered into Federal service on August 9th. All three were under the command of Colonel Dwight Morris from the Connecticut regiment, the most senior of the neophyte colonels.3 Palmer’s concern about the 108th‘s lack of preparation probably reflected the mind set of the other regimental commanders in the brigade when the march resumed on Sept. 9th. In the succeeding days, as the men kept more together and "became inured to tramping" the regiment passed through Clarksville, then Frederick and on Sunday, Sept.14th, paused near the Catoctin mountains where they observed the fight for Fox’s and Turner’s Gaps at South Mountain, six miles in the distance. Although new to the army, the recruits had learned to take advantage of any pause to get food as soon as possible. They immediately started cooking fires to roast their filched green corn but, just as the meal seemed feasible, the order to fall in was given “and the simmering corn was reluctantly thrown away.” They started once more, marching until dusk, but then at midnight their short repose was broken when they moved again towards Turner’s Gap and bivouacked near the battlefield around 2 a.m. So tired and worn out were they that some men slept deeply within 30 feet of Rebel corpses. The march continued through the next day, until they settled into camp on the other side of Boonsboro.4

On the 16th, as the men from Monroe County marched towards that fateful field on Antietam Creek, fatigue and fear must have made the march seem paradoxically lengthy and short. The hot weather and the red dust of the Maryland roads slowed the march at times to a crawl but what awaited them at Sharpsburg drew closer and closer with increasing speed. Thoughts of mortality and second guessing their decision to enlist surely filled their minds. Some members of company F began to speak loudly and gave voice to their fear and frustration. An officer on horseback, passing nearby ordered “Silence in the ranks!” Chauncy Harris, who always tried to keep his company mates in good spirits, took exception to the martinet and retorted “Go to the devil, you lazy son of a gun; why don’t you give some poor soldiers a ride?” More then likely Harris used saltier language but the officer just laughed and rode on. Minutes later, Harris found out that he had just conversed with General French, their division commander. The moment of hilarity passed. The dust continued to be churned and the regiment became shrouded in a nervous silence. Suddenly and unexpectedly, the tension was relieved outside of Keedysville when "the vocal element of Company G, led by little George R. Davis, broke out sweetly and enthused the boys with inspiring refrains." The sound of their own singing helped to relax the regiment as voices raised in song released the emotions deep within and created a sense of unity beyond fear. Whatever lay ahead at Sharpsburg, they would face it together but for some the melodic echo of that moment would be with them for the last time in Roulette’s cornfield the next day.5

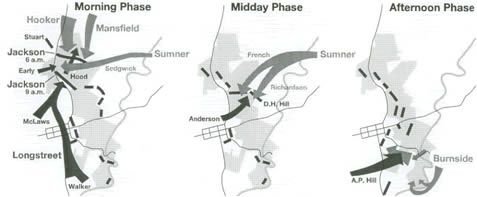

The battle of Antietam or Sharpsburg can be divided into three separate but related actions. On the morning of the 17th, Hooker’s 1st Corps initiated the first phase of the battle in the North Woods by attacking Lee’s left flank. This fight which swirled in fury around Miller’s Cornfield involved some 2nd Corps’ elements as well as 12th Corps’ units. Towards noon, as this initial action subsided, the fury was picked up and fanned into combustion in the center of Lee’s line at a part of the field that would become known as "Bloody Lane", south of the East Woods and the Dunkard Church. In the afternoon, the final phase of the battle was Burnsides’ belated assault at the Rohrbach Bridge which succeeded at first, only to be defeated by the timely arrival of A.P.Hill’s Division from Harper’s Ferry. For the fledging soldiers of French’s Second Brigade their first experience of combat took place during the second phase of the battle in the attack on "Bloody Lane".

Battle of Antietam. Sept.17,1862

(Map from National Park Service website)

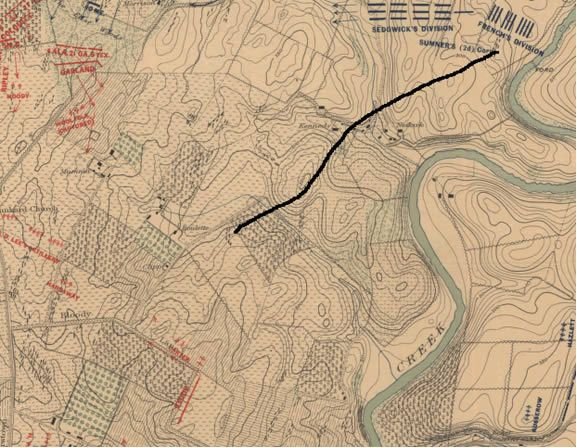

Early on the morning of September 17, French’s Division moved along the eastern side of Antietam Creek, towards the upper bridge, north of Sharpsburg and crossed the creek just south of the bridge "in the vicinity of Pry’s Ford".6 In the pre-dawn hours before marching, the men received 80 rounds of ammunition, as well as double rations. Some of the men ate their rations right away to be sure they could enjoy them now, reasoning what good are rations to dead men? They could worry about food after the battle. The 108th New York was the rear of the brigade column which was led by the 14th Connecticut, followed in order by the 130th Pennsylvania. Since "there were two other columns crossing and there was but one bridge", the brigade waded the knee deep water of the Antietem.7 Private George Washburn recounted that some of the men of the 108th showed remarkable composure before their first battle since "several of the boys evinced no desire to go into battle with wet feet, and so stopped to pull off their foot-gear, rolled up their pants, forded the stream and coolly sat down again to replace their pedal adornments." While these so-called ‘cool customers’ adjusted their sartorial appearance, the air was full of "red hot anathemas" from the impatient officers.8 In the 14th Connecticut, the lead regiment, Sergeant Benjamin Hirst noted a similar occurrence but with a different objective. Hirst explained that "some of the boys wanted to take off their shoes and stockings to keep their feet dry, and here two or three left us not to be seen again that day."9 As could be expected in any regiment, let alone a novice one, there were those who were not anxious to see the Elephant, a term the troops used for combat experience. For those who remained, however, the Elephant was just over the crest and at the base of the Roulette farm ridge, in a sunken road that intersected the east side of the Hagerstown Pike, about 1500 feet south of the Dunkard Church, and zigzagged roughly southeastward until it combined with the H .Piper farm lane and intersected the Boonsboro Pike at the Keplinger farm located east of Sharpsburg.

The Route of French’s Division to the Sunken Road, Morning of Sept. 17, 1863.

(Map based on the Carman-Cope maps –available on the Antietam Battlefield, Professional Military Education CD.)

‘Bloody Lane’ was an old wagon road which, through extensive use, had become sunken and thus provided an excellent parapet for infantry. Facing north for the first quarter mile this road turned slightly to the southeast just before it intersected the southern end of the Roulette Farm lane. Directly in front, or north of the road, was a crop field that rose to the Roulette Farm ridge, about 100 yards away. From their position in the road, the Confederates could advance skirmishers or even a line of infantry to the southern crest of the ridge and thereby keep a fire on the Federal troops who ascended the northern side of the ridge. If overwhelmed, these forward Rebels could simply descend the ridge and rejoin the main Confederate line posted in the sunken road. The major flaw in the position was that it was actually a slight salient and could be subjected to enfilade fire if enough Federals could secure the ridge line to its front, which sloped gently upward to the east and closer to the road. Once on the ridge, Union troops could almost fire down into the road and as their reinforcements deployed along the crest towards the east, they would eventually flank the Rebels and could fire along the line of Confederate infantry in the road. General D.H Hill, Stonewall Jackson’s brother-in-law and his infantry were ensconced in the road and the job to drive them out fell to French’s Division. Although just how the lob became French’s was by no means clear since he and his division should have been following Sedgwick’s Second Corps division through the East Woods to the West Woods, where disaster awaited them. A member of the 20th Massachusetts wrote that French “separated himself from Sedgwick” but whether by “accident or under orders” could not be determined. Another explanation was that French intended to swing into line on Sedgwick’s right and as he first faced south to start the movement, he was attacked by Hill’s advanced pickets in the area of the Roulette farm so he continued on south towards the enemy.10 No matter how or why he got there the one thing that was clear was that French’s Division would attack the sunken road. Weber’s Brigade led off the assault on the western section of the road but was repulsed since most of the firepower from Hill’s men was concentrated on them. Morris’ Brigade, to which the

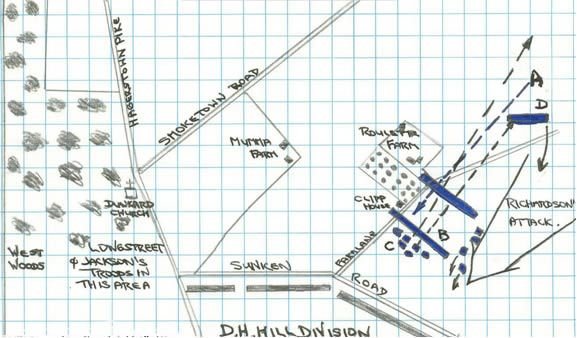

108th belonged, deployed behind and slightly to the left of Weber’s troops. The 14th Connecticut, the brigade right, was in the cornfield, west of the Roulette Farm,11 while the centre regiment of the brigade, the 130th Pennsylvania, was in the orchard, south of the Roulette farmhouse and just west of the Clipp House. The 108th New York formed the brigade left, with its right in the area of the Clipp House on the farm lane running north from the sunken road to the Roulette barn,12 while its left was unsupported as McClellan typically fed the brigades into battle in a piecemeal fashion.. Coming up the crest behind the 108th was the left half of Kimball’s Brigade, the 132nd Pennsylvania and the 7th West Virginia.

Morris’ Brigade moved in a line of battle towards the crest of the Roulette ridge marked by the fence south of the Clipp house. Pierce remembered that the rightmost company,’A’, had problems maintaining a battle line since it was just west of the Roulette lane and the farm buildings had to be circumnavigated in good order. After the initial obstacles, the regiment moved to the fence on the crest where they "laid down for a few minutes to get breath." When the right of the regiment attempted to clear the fence in order to attack the rebel position in the sunken road, the movement was impeded by skulkers from the 4th New York of Weber’s Brigade who, eventually, skedaddled "back down the hill"13 while the 108th moved onto the ridge crest overlooking the sunken road. When the regiment reached the crest of the Roulette farm ridge and started to take severe fire from the rebel position below, the trouble began. At the top of the ridge, the 108th froze and would go no further.14 The fury of the Confederate fire, artillery bursts, saltpeter and smoke burning the eyes, the new turned earth slippery with blood, wounded men screaming and crawling on all fours, and the omnipresent ‘thunk’ of minié balls driving through cloth into flesh, overwhelmed the novice regiment and paralyzed its forward motion. For the Confederates in the sunken road, the Federal soldiers were prime targets, silhouetted against the sky. On the right of the battle line, Private Joseph Delevau of Company D collapsed, writhing in pain, with a bullet through his thigh. He was carried on a stretcher to the cover of a hay stack but drummer Sanford Cassidy, concerned for Delevau’s exposure to fire, had him moved shortly before a large shell tore up the exact spot where he had been originally placed. William Chapman, who’s Company A formed the extreme right of the line, was shot in both hands, crippled for life and out of the war. George Goff, the regimental flag bearer in the center of the line, was shot in the forehead with buckshot. Before the regiment left Rochester, Goff had visited his wife’s grave and predicted that he would never see her resting place again. His wound did not seem serious and was dressed in a field hospital, where he also found time to write a letter to his brother, before he returned to the battle. With blood "trickling from the center of his forehead to the end of his nose", he wandered aimlessly around the battlefield, only to die three miles away in a Keedysville graveyard. Perhaps he found his beloved wife after all. On the 108th’s left, Lt. Robert Holmes, who the evening before expressed his desire for victory or death, was in advance of Company G and exhorting "‘follow me boys’ when a ball tore out the side of his neck" In silence he died, his desire fulfilled. Private Byron ‘Pliny’ Holcomb, the quiet Quaker of Company G, in the midst of reloading, suddenly gasped then slumped over. A ball had struck him "about six inches above the point of the hip” and passed through his body. He asked simply to be carried back then died. Beside him, Charlie Tillotson, also 19 years old, took a mortal head wound and expired three days later. Both boys were from the town of Henrietta, N.Y. Charles Spring took a bullet in the left forearm. A few days before the battle, he was the drummer of Company H but “exchanged” his “drum for a musket.” The ball in his arm would never be extracted. On the extreme left Company B was fighting for its life. Since they were unsupported on their left, the men took fire from front and flank. Chester Hutchinson watched helplessly as Lieutenant David Tarbox fell, shot in the forehead, followed by Corporal Erwin Payne with a debilitating wound to the calf of his left leg. Hutchinson continued firing until he felt a searing pain in his chest. A ball had pierced his right breast but deflected off his sternum, “coming out about four inches from where it entered and stopping against my right arm.” A fellow company member, Franklin Garlock, reloading after his tenth shot, was brought down with a hideous face wound. A ball or piece of shell struck him "just below the right eye, passed "through the right side of the head" and exited through the right ear. He lay unconscious on the field and was roused only by his comrades falling or stepping on him as they fell dead or wounded .He was carried to the rear as the danse macabre on that fire- swept-ridge continued without pause. Hutchinson and Payne reached a field hospital. Tarbox was dead on the field. Their "numbers were so severely decimated" that the New Yorkers “withdrew to the meadow over which they had advanced."15

Actions of the 108th New York at Antietam.

A. 108th NY moves into position on the far left of Morris’ Brigade.

B. 108th takes fire from the Sunken Road –casualties mount – Major Force is killed in this action.

C. 108th relieved by Richardson’s Division going into action – discipline breaks down, some join the attack, some run.

D. What remains of the regiment reforms to support Richardson.

The actions of the regiment after it fell back from the crest are by no means clear. When the 108th New York fought at Antietam, the regiment was barely a month old and had less than three weeks of military instruction. They displayed obvious courage in their first engagement but the men suffered from a lack of assertive leadership. Just after the Rochester men took position on the ridge crest, the regiment suffered the significant loss of a superior field officer, George B. Force, a Rochester native, who was mustered in as major on August 18,1862 . "While in the act of giving an order to his men" the thirty-year-old Force was "struck by a rebel bullet" and his death had dramatic ramifications for the performance of the regiment.16 Captain Pierce of Company ‘F’ explained that the regimental battle line "advanced guiding center ", with a left and right wing formation and six paces behind the color guard. The left wing of the regiment would be under the command of the senior major, or in this case, George Force while right wing, which included Pierce’s company ‘F’, would be under the command of the lieutenant colonel.17 However the 108th had no lieutenant colonel so Palmer told Force "to give his attention to the left wing and I would take care of the right wing."18 George Force was also "a superior drill officer" and "to him the regiment owed largely the rapid progress it had made in drill and discipline."19 Therefore when the major went down the men of the left wing lost a potentially stabilizing influence and when the regiment started to waver, no one took control to maintain order.

Apparently over the next few hours, there were numerous attempts to reform the NewYorkers. The regimental history states that " Sumner ordered the line to be reformed under fire, but the test was too severe for volunteer troops under the storm of shot and shell falling about and among them."20 Captain Pierce of Company ‘F’ described the further confusion that occurred when the regiment was relieved at 12:30 p.m. by Barlow’s regiments who successfully charged the sunken road. He recalled that part of the regiment joined Barlow’s charge,

and the rest fell back to the foot of the hill to reform again. Some of the regiment I am sorry to say kept falling back after having fought splendidly and didn’t stop falling back until they reached our former camping ground, about 2 miles. About a hundred fellows however stuck to the colors and after the utmost exertion on the part of some of the officers were again formed in line of battle, after which we moved off towards the left, halting on the same line of fence that I have spoken about on the brow of the hill.21

Just how many Rochester men joined in the final charge, around 1:00 p.m., cannot be known with certainty. For those that did, the carnage in the sunken road was ineffable. In the worn part of the road, human "blood in streamlets coursed down its gulleys, and here and there lay in pools suggestive of the abattoir."22 The lane was literally packed with bodies. At one spot, "thirteen dead bodies lay on a heap" and at "other places they lay two, three, even five deep." On the top rail of the fence at the southern side of the lane hung the body of a Confederate soldier with seventeen bullets in it.23 In his effort to climb out of the sunken road and escape, he had been transformed into a macabre silhouette against the evening sky. Another had died in a kneeling position, rifle perfectly balanced, ready to fire, with a bullet through his brain.24 Lifeless eyes, fixed forever on an empty gunsight. Colonel Palmer did not join the charge on the sunken road. Instead, he followed orders, fell back 100 rods and attempted to reform on the colors. Once here he found that he had only "about 100 men" available but, as Pierce mentioned earlier, was ordered to the fence line on the ridge brow again "to fill a gap in the line of battle farther to the left". The command did so and "remained there under a severe fire from the enemy’s batteries until the close of action at dark." Later that night, just as the regiment settled down to sleep or grab some food, the weary remnants of the 108th drew picket duty.25

At Antietam, the regiment suffered a total loss of 195 in killed, wounded and missing in its “first baptism of burnt powder” but historically, its reputation suffered also. Forty two years later, Fred Hitchcock of the 132nd Pennsylvania, wrote a damning description of what is believed to be the 108th and its colonel at the battle of Antietam. Hitchcock was Adjutant of the 132nd PA., part of Kimball’s Brigade which was directly behind Morris’ Brigade, in the assault on the sunken road. According to Hitchcock, at the critical moment of the fight on the ridge, he found "a body of troops", "lying idle" under a tree on the safe side behind the crest and its colonel was "hugging the ground" overcome with fear and unable to move or speak coherently. The young Adjutant, the story continues, was ordered to get the 108th moving and was further authorized to shoot those who refused. With gun drawn, he once more approached the New Yorkers but before it became necessary to execute the "skulking colonel", the major of the 108th leapt to the fore and attempted to move the men by “swinging his hat and cheering his men forward.” Unfortunately, at that moment “a solid shot decapitated" the major but his example led “the other officers bravely” to rally the regiment and to push it “forward to the firing line” leaving the colonel quaking pitifully on the ground.26

Hitchcock, the sole source for the story, never names the regiment number or its state designation. Why the alleged "body of troops" is identified as the 108th New York seems to be derived from the geographical positions of the regiments involved in the attack. Since the 132nd Pennsylvania followed directly behind the Rochester men, therefore it must follow that the 108th New York, lolling under a tree, was the "body of troops" described by Hitchcock. If these lolls belonged to a New York regiment, they could have been the 4th New York of Weber’s Brigade whom Pierce claimed to have encountered as they skedaddled. The report on the activity of the 4th New York is conspicuously absent from the Official Records of the battle. However, if Hitchcock did intend the 108th New York, then his account is quite dramatic and, like most drama, appears to be more fiction than fact and may be the creative work of an aging mind in need of self-aggrandizement or revenge.

There are a number of problems with Hitchcock’s description if, in fact, it is a description of the 108th New York. From both Pierce’s letter and Palmer’s report, it would appear that Hitchcock came across the 108th after it withdrew from the crest and was reforming. The regiment had already been on the firing line where it suffered its first set of casualties. All the sources admit that there was difficulty in bringing order out of the chaos, but none mention a picnic-like repose under a tree. That Major George B. Force was killed before Hitchcock arrived is confirmed by Colonel Palmer and the regimental history. Force fell "early in the action" and was among the first killed on the crest of the ridge before the regiment broke for the first time.27 Colonel Palmer, who claimed to be located "directly in the rear of the centre of the regiment and within twenty feet of the line", may not have provided active or aggressive leadership for his men, but it does not necessarily follow that he lacked courage or hid terror-stricken on the northern face of the ridge. The fact that the division commander’s report is not generous in accolades to Morris’s Brigade but extols the heroics of Kimball and Weber is not necessarily a validation of Hitchcock’s account. French, later in the report, mentioned Morris and the 14th Connecticut but his failure to commend Palmer and the 108th New York could have originated from a different motive.

On the evening of September 7, after Palmer had been ordered by Sumner to report to General French, the division commander, the Colonel of the 108th claimed that, when found, the General was quite drunk. As Palmer delicately recalled, French, on that particular Sunday evening, "was not at prayer yet in an elevated Spiritual condition." Palmer, obviously unimpressed with "Old Blinky" French, "left with serious forebodings as to the future and for the first time with really a sad heart."28 Early the next morning, Palmer’s concern was strong enough to lead him to forego military etiquette and appeal directly to the Commanding General, George Brinton McClellan. Palmer requested that Little Mac shift the 108th New York "to some other division than General French’s." McClellan simply asked, "Why?" After some further coercion, the colonel answered plainly that "I wished to avoid if possible placing my command or myself under an officer of intemperate habits." McClellan looked troubled, dictated a dispatch to General Sumner but understandably did nothing to fulfill Palmer’s request. McClellan could hardly embarrass a battle tested West Pointer and career officer who, like many of the officers in the Army of the Potomac, indulged a fondness for spiritual refreshment, at the request of a rookie volunteer colonel from upstate New York. However, the important issue here was whether or not French found out about Palmer’s distaste and reluctance to serve in his division. Given the close knit attitude of the professional regular army early in the war and the distrust of volunteer officers, it would be a safe bet to assume that French heard of Palmer’s request. The validity of such an assumption could explain a further confrontation between the general and the colonel that occurred on the evening of September 12, five days before the battle.

In the fall 1862, the war was still young and the belief that the struggle could be conducted in a gentlemanly manner, based on noble behavior, high morality and civilized rules of warfare, still prevailed, especially in the mind of George Brinton McClellan. Therefore, on the march into Maryland there were strict orders against marauding and the destruction of Rebel civilian property. Although Palmer’s initial complaint against French had been ignored, the Colonel noticed that the General seemed to have him marked "and watched me pretty closely for an opportunity for the display of his power". Such an opportunity arose over some Rebel "refuse straw." On the evening of Sept. 12, near Urbana, just south of Frederick, the 108th camped on a plantation owned by a Rebel soldier in Lee’s army and some of the Rochester men, without Palmer’s knowledge or consent, “got permission from the overseer to take from the barn yard some of the refuse straw to sleep on and relieve them from the bare ground." Old Blinky spotted the removal of the straw and, probably well fortified against the cool September evening, proceeded to throw a full-blown, red-faced, temper tantrum at Colonel Palmer whom he suspected as the mastermind behind the used straw caper. Palmer, mortified in front of his men, was threatened with arrest and leg irons. The Colonel sealed his fate when he calmly requested that French “please address me as you would a gentleman" and evoked a titanic explosion from the General who arrested him on the spot. Incensed at Palmer’s treatment, the men of the 108th were ready to demolish Division Head Quarters but by the following morning the affair had been settled and the Colonel returned to the head of his regiment. A quiet truce was declared between Old Blinky and Palmer as the division moved towards Antietam. If Oliver Palmer had behaved in the cowardly manner that Hitchcock attributed to him, French would have known about it but no reports, either at regimental, brigade or division level, so much as hint of such an act of cowardice on the part of Palmer and his regiment.29 French’s oversight in his report may be attributed to a lack of first-hand knowledge since the 108th New York was forced by geography to fight separated from the rest of its brigade and not under the direct control of the general. In his report Palmer mentions that, at one point, the regiment received orders from General Richardson and General Hancock.30 As a final explanation perhaps French simply did not like Palmer and his prudish ways, and thus chose not to mention him. No matter what the reason, other than Hitchcock’s forty-two year old recollection, there is no clear evidence that the regiment or its colonel behaved with dishonor at Antietam. Captain Francis E. Pierce’s letter to Edward Chapin after the battle makes no mention of Hitchcock’s incident but Pierce does imply some weakness in leadership: "Colonel Palmer is popular with the men. He is brave but oh how he lacks in military knowledge."31 Pierce was not a man to hide his feelings in a private letter to a friend. In his other letters, he was quite candid and unconventional in his comments. He was also one of the bravest individuals in the 108th so it would be inconceivable for him to tolerate quietly the alleged cowardice of Colonel Palmer. Hitchcock’s story still clings like a soiled stain to the reputation of the 108th New York and was routinely cited as historical fact in a recent study of the battle. Finally, Hitchcock’s account may have had a more sinister motive which came to light after the fight at Sharpsburg. In a letter written on Oct.6, 1862, Lt. Charles P.Klein of the 140th New York, another regiment raised in Rochester, described his visit to the camp of the 108th New York. Klein was eager to talk about the battle since the 140th had not yet been engaged in combat. When the conversation turned to the death of Major Force, whose brother was a major in the 140th New York, Klein recorded that the “impression of the men is that Major Force, as well as many more wounded, was shot by the Pennsylvania regiment in the rear” which would have been the 132nd PA., whose adjutant was none other than Fred Hitchcock. Did Hitchcock disgrace the 108th in order to cover up the jittery behavior of his own regiment? Whatever the reason, of the 200 casualties, sustained by the 108th New York at Antietam, most of them fell facing the enemy.32

All in all, the 108th New York behaved about as well as could be expected during the bloodiest day of the civil war and their battle losses are not out of line with those in the other regiments in Morris’s brigade. With under understandable pride, James Moore of Company B expressed in almost breathless phrases to his friend that “the young 108 fought with desperation boys as well as men in some instances the boys done best but let there be no more talk about boys. I wish you had seen the boys fight, you would feel proud of them.” With less than three weeks training, they were somewhat less than green and as General French pointed out:

The conduct of the new regiments must take a prominent place in the history of this great battle. Undrilled, but admirably armed and equipped, every regiment, either in advance or reserve, distinguished itself, but according to the energy and ability of their respective commander.33

Although some men were terrified by the slaughter, others said they were "indifferent" or even enjoyed the chaos. Captain F.E. Pierce found army life exciting, a welcome break from the routine existence of teaching. With his full flowing beard of Old Testament proportions and large six foot frame, Pierce carried the aura of the warrior. At the height of the fury on the ridge at Antietam, while men fell all around him, Pierce recalled that "I was never more cool in my life" and seemed to thrive on the love of terror.34 However an event did occur during battle that could be seen in retrospect as prophetic for the 108th New York and its slide into relative obscurity. Private Henry Niles of Company ‘K’ had taken part in the final assault on the sunken road and had managed to capture the regimental colors of the 14th North Carolina. Such an accomplishment usually won great renown for the capturing regiment and, for the captor, usually a Medal of Honor. However

after taking the colors some officer of another regiment told him to give them up, stating that if he carried them he might be fired into by our own men. Not knowing any better, he handed them to such officer.

There must have been an organized scam about battle flags going on that day, since General Kimball, the leader of the brigade behind the 108th, reported the pilfering of "several stand of colors, which were taken by some parties outside of my brigade."35 Their first battle had been an auspicious beginning for the boys from Rochester but their entire hard won honor was either maligned or picked up and taken by another.

Endnotes.

1 Capt. Calvin D. Cowles, compiler, Atlas To Accompany The Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1891-1895), Plates, 6, 7, 8, 89. These maps show the defenses of Washington at the time of the war. To east of Fort DeKalb was Camp Palmer. The route of the 108th, as well as the landmarks mentioned, can be noted on these maps. Hereafter cited as O.R. Atlas, followed by the plate number and map number if appropriate.

2 Palmer-Diary, p.28-30 ; 108th New York, pp. 18, 333.

3 Dyer, Part 3, pp.1012-13, 1448, 1614-15 ; Charles D. Page, History of the Fourteenth Regiment Vol. Infantry (Meriden, Connecticut: The Horton Printing Co.,1906) rpt. Higginson Book Company (Salem, Mass: Higginson Book Company, 1998), p.14. Hereafter cited as 14th Connecticut ; Edward W. Spangler, My Little War Experience(York, PA.: York Daily Publishing Co. 1904) rpt. Higginson Book Company (Salem, Mass.: Higginson Book Company, nd) p.18 ;108th New York,p.188. The latter three sources reveal that Morris was appointed colonel in May/62, Palmer in July/62 and Levi Maish of the 130th PA. in Aug./62, thereby making Morris the senior colonel.

4 Morris Darrohn, letter to his family, Sept. 20, 1862, typescript of the original letter, courtesy of Mr. Ron Erwin, Rochester, N.Y., from his unpublished manuscript of the letters of Morris Darrohn. Hereafter cited as Darrohn-Letters ; 108th New York, p.19

5 Ibid. p.21,391.

6 Oliver C. Bosbyshell, comp.&ed.., Pennsylvania at Antietam (Harrisburg: Harrisburg Publishing, 1906),p. 161.

7 Francis Edwin Pierce,"Civil War Letters of Francis Edwin Pierce of the 108th New York Infantry,"Rochester in the Civil War, Blake McKelvey, ed.(Rochester: Rochester Historical Society Publications, 1944), pp.153-54. Hereinafter cited as "Pierce".

8 108th New York, p.24.

9 Benjamin Hirst, The Boys From Rockville, Civil War Narratives of Sgt. Benjamin Hirst, Company D, 14th Connecticut, Robert L. Bee, ed.(Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press,1998),p.22. Hereafter cited as Boys from Rockville.

10 F.W.Palfrey,The Antietam and Fredericksburg(New York:Charles Scribner’s Sons,1881-83) rpt. The Archive Society (Harrisburg,PA.: The Archive Society,1992),p92 ; James V. Murfin, The Gleam of Bayonets (Baton Rouge : Louisiana State University Press,1965),p.246.

11 U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies,( Washington: Government Printing Office,1889), reprint by Historical Times Inc.(Harrisburg: The National Historical Society, 1985), series I, vol.19 part 1, p. 332. Hereafter cited as O.R. and all further references are to series I unless otherwise specified.

12 108th New York, p.386 ; O.R.,19,1, pp.334-335;

13 Pierce, p.153.

14 Pierce, pp.153-154, and 108th New York, p. 24.

15 108th New York, pp.17-18, 25,24,155,158,193,237, 273, 262, 315 ,387-388; R.L. Murray, Before the Appointed Time (Wolcott, N.Y.:Benedum Books,2001), p.59.

16 Pierce,p.153; Brig.Gen. Silas Casey, Infantry Tactics (Dayton,Ohio: Morningside,1985), pp.9-17; plate 1. Other information about the unit formation was acquired by the author from personal communication with David Murphy who shared his expertise. Mr. Murphy writes the monthly article entitled "On the Line" in The Civil War News.

17 108th New York,p.25.

18 Palmer-Diary, p.44.

19 108th New York, p.161.

20 Ibid., p.25.

21 Pierce, p.154. Emphasis in original.

22 Bosbyshell, op.cit.,p.164.

23 Ibid.,p. 175.

24 108th New York, p.24.

25 O.R.,19,1,p.335.

26 108th New York, p.262; Frederick L .Hitchcock, War from the Inside (Philadelphia: Press of J. B. Lipponcott Company, 1904), reprint Time-Life Books Inc.,(n. p.: Time Life Books,1985),p.60-61.

27 O.R.,19,1,p.335. 108th New York, pp.24,193.. Hitchcock has confused the death of Force with the death of Frank Johnson, an "aid to Colonel Palmer" who died while trying to reform the line. He had his head taken off by a round shot (p.25). Pierce also confirms that Johnson died by artillery fire. Coincidentally, the major of the 140th New York was Isaiah Force, the brother of George. Isaiah received news of his brother’s death shortly before the 140th was scheduled to depart from Rochester. He was drilling the regiment when told of the death and was urged to return to the city to inform his father. He resumed his place on the field and decided to march with the regiment. See Brian A. Bennett, Sons of Old Monroe (Dayton: Press of Morningside,1992),p.53.

28 The Boys from Rockville ,p.127; 108th New York, p.39 ;14th Connecticut,p.115;Palmer-Diary, p.30-31.

29 Palmer-Diary, pp. 31, 36-38. For a slightly different version of the "Hay Caper" see 108th New York ,p.391; O.R.,19,1, pp.330-331,326-328, 333-334,335-336,332-333,323-324.

30 O.R.,19,1, p.335. The majority of the 108th fought on the eastern side of the Roulette farm lane while the 130th PA and 14th Conn. fought on the western side. So it would not be inconceivable for the regiments to lose sight and contact with each other. In fact Morris in his brigade report mentions only the actions of the 130th and 14th (O.R.,19,1,p.333) .

31 Pierce, p.156.

32 John Michael Priest, Antietam: The Soldiers’ Battle( Shippensburg: White Mane Publishing Company, 1989),pp.171-172. Hitchcock’s story is presented verbatim without any attempt to evaluate its accuracy. The information about Klein was obtained via email from Brian Bennett to Ron Irwin and thence to the author who wishes to thank both men. Mr. Bennett, author of Sons of Old Monroe, explained that the letter had been printed in a local newspaper in the Geneseo area of New York State.

33 O.R.,19,1, p.324. James Moore to J.Fellows, Sept 29,1862, Fellows-Moore Correspondence, originals in the Department of Rare Books, Special Collections and Preservation, University of Rochester. These letters are used with the kind permission of the University of Rochester. Hereafter cited as Moore-Letters.

34 Pierce, p.154.

35 O.R.,19,1, p.327,335