Chapter Three

Rochester's Forgotten Regiment:

The 108th New York In The Civil War

By Terence G. Crooks

Chapter Three:

Into The Vortex Of Death

With the fortuitous and dramatic arrival of A.P.Hill’s division and its flank attack which stopped Burnside’s men after they finally crossed the bridge that would henceforth bear his name, the fighting on the 17th of September ended. Both armies were lighter by 22,719 casualties but the Federals, who at the start of the battle outnumbered Lee almost 3 to 1, were able to absorb the horrendous losses with more equanimity than the Army of Northern Virginia. In fact, McClellan still had Fitz-John Porter’s entire Fifth Corps and most of Franklin’s Sixth Corps in reserve, a total of almost 25,000 men. But Little Mac, still fearing Lee’s fantasy force of 100,000 men, wished only good riddance to the Rebel chieftain and his crew. So, on the 18th while Lee stood defiantly daring the Federal commander to attack his threadbare force, McClellan did nothing but watch since he did not wish to jeopardize his questionable victory by engaging Lee and his ‘hidden’ reinforcements. Besides, those “in whose judgment” he relied, including himself of course, told him that he “fought the battle splendidly & that it was a masterpiece of art” so there was little need for improvement. Apparently, Fitz-John Porter, one of the general’s closest sycophants, also must have fancied himself as an art critic. Consequently, when Lee and his ragged remnants crossed the Potomac back into Virginia on Sept. 19, McClellan was glad to see him go and never seemed to comprehend the opportunity that he had lost. For the next while, seven weeks to be exact, McClellan intended to guard the line of the Potomac and attend to “the equipment and reorganization of his command.” 1

At 6 a.m. on the 22nd of September,1862, the 108th New York followed orders and began the march to Harper’s Ferry. As the regiment and its brigade mates marched down the Hagerstown Pike, “passing the battered and shot riddled Dunkard Church” then on through Sharpsburg, the reddish dust from the road was thick yet not as thick as before since they were far fewer. Now however, they marched with the swagger of veterans who had seen the Elephant and lived to speak of it. One twenty-year old wrote to his parents with a certain degree of pride that since “I am in the army I have got so I can eat pork first rate” even while on the march when “I could not stop to cook it” and had to eat it raw with hardtack. Although hardened by battle, these new veterans found the march of 15 miles down the road, traversed six days earlier by A.P.Hill’s men, difficult and tiring. September warmth and dust combined with post battle fatigue to make the march a tremendously “hard task.” Trying to “close up, close up all the time” proved impossible and the officers and men were falling out every mile. At Harper’s Ferry, the bridges had been destroyed so, in order to reach Boliver’s Heights on the Virginia side, the men were forced to ford the Potomac, an event that generated much hilarity. While the band of the 14th Connecticut played ‘Dixie’ or ‘Yankee Doodle’ some “men desirous of getting across the river dry shod” put too much trust in their ability to negotiate the “slippery rocks” and “would go under the water, blowing like a porpoise and dripping wet” when they emerged. At this spot, the river “was only knee deep some places a little deeper” so the image of a whole column of men “with their pants rolled as high as they could get them” struck one member of the 108th as “quite comical.” When a fastidious officer went under, the merriment increased ten fold.

Fording the Potomac provided a break in dreary march and once across, the New Yorkers “toiled up the steeps southward from the Ferry to Bolivar’s Heights, and pitched their tents near the brow of the same.” Southwest from the Heights the men could see the “spires of Charlestown where John Brown was hung”, some “6 or 8 miles” away, while across the rivers Shenandoah and Potomac loomed the Heights of Loudoun and Maryland respectively.2 Despite the post-card views and “beautiful sunrises”, the men soon realized that Harper’s Ferry was a "desolate and wretched place for a camp." Just prior to the battle of Antietam ,the arsenal had been surrendered to Jackson in mid-September so by the time the Federal army re-occupied the site, everything of value "had been destroyed" and nothing remained but "ruins, vermin and filth." Palmer’s disgust with the camp was further aggravated by his frustration with army red tape. Unsuccessfully “for an entire week”, he tried to get permission from Superior officers to send an officer to Washington to bring forward the baggage of the officers & knapsacks of the men". Men in the 108th were reduced to one vermin-ridden shirt which they had worn since September 7th, when they left Washington for Maryland. As the number of sick and dying continued to rise at an alarming rate, the Colonel of the 108th New York decided that an end run was in order to relieve the suffering of his men. With this goal in mind, Palmer "detailed my Hospital Steward

and gave him a short certificate stating his position and requesting him to proceed to Washington to procure medical stores for the sick who were dying for want of them, telling him to go through unless shot or impaled on a bayonet...I told him further that when he got to Washington not only to get the medical stores but at all hazards to procure the needed baggage and knapsacks. I was aware that I was liable to be cashiered for this proceeding but I preferred to take the chances rather to remain idle amidst so much suffering and want. The plan succeeded admirably.3

Once the men received their belongings, they quickly settled into the routine of camp life where the only major inconvenience, other than the war itself, was a one mile walk for fresh water. They drilled “about 4 hours per day” and, with the exception standard guard duty, had time to eat well, write home and swap tales of “hair breadth escapes and deeds of valor” with fellow soldiers and family.4 In early October, the monotony of camp life was broken by a visit from President Lincoln but the “regiment saw him only at a distance.” Professor Lowe and his aerial reconnaissance balloons ascended daily to provide some degree of distraction for the men, but the reality of war was never far away. Here, the men learned of the death of Miles Casey of Company ‘K’. Wounded and left behind at Antietam when the regiment marched, Casey had been a veteran of the British army and had seen action in the Crimea and in Canada. He was selected as the standard bearer of the state flag for the 108th and had carried it proudly until he was shot at the crest of the Roulette Farm ridge. Casey dropped the banner which was picked up by Lt. Bloss and stumbled down the incline towards the frame structure, generally called the Clipp House. Later, during a lull in the battle, Casey was found “lying in a corner” of the house that had been ‘cat-holed’ by round shot. A shot passed through the walls “within two feet of him” but Casey quipped that he had got “used to ‘em”. To his rescuers he maintained a cheerful demeanor and although “he had been badly struck”, claimed “he would come out all right.” General McClellan happened to be passing by at the time of the burial service for Casey and, upon learning the details of the standard bearer’s death, Little Mac and his staff removed their hats until Casey’s body was lowered into the grave.5

While in camp the men also learned of the promotion of Francis E. Pierce, formerly captain of company F to the position of major, recently vacated by the death of George Force. The regiment also acquired a lieutenant colonel in the person of Charles J. Powers. Like a number of other volunteers, Powers was originally a Canadian, born in Northumberland Township, Canada West ( later Ontario) on June 7,1833. Very little is attainable about his early life and education. According to the 1894 version of the regimental, Powers attended University of Toronto while still a native of Canada, but University of Toronto has no record for him.6 Once he immigrated to Rochester, he furthered his education at Harvard where he studied chemistry at Lawrence Scientific School from 1851-52, but returned to Rochester to enter the law office of Farrar and Durand. He was admitted to the bar in 1854.7 With the outbreak of war, the five foot nine, dark complexioned Powers, probably caught up in the initial patriotic fervor or fever that engulfed Rochester after the attack on Fort Sumter, did his duty and volunteered to protect and preserve the Union. Powers served as Adjutant of the ‘Bloody Thirteenth’ through Bull Run and McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign of 1862, but soon won promotion to Captain and Assistant Adjutant General. He held this position until Sept.23, 1862 when he received the vacant lieutenant colonelcy with the newly formed 108th New York Volunteers.8 Both Pierce and Powers were twenty-nine years old and were born within a month of each other. While Charles Powers was practicing law in Rochester, Francis Pierce entered the freshman class at the University of Rochester and graduated with honors in 1859. During the last two years of his college career, he functioned as an assistant teacher in a local church run school for boys. Upon graduation, Pierce was appointed as principal of the Mt. Morris Academy for the academic year of 1859-60. However, when his cousin, Colonel Samuel Pierce, established the Rochester Military Training school in the fall of 1860, he was appointed as head of the school until he enlisted in August of 1862. From October 1862 until the end of the war, the 108th New York would be in the hands of one or both of these men. In the subsequent months and up to his resignation in March of 1863, Colonel Palmer would have little direct influence on the regiment as a combat unit.9

In the early fall of 1862, change was in the air. The first one came to the Second Corps who experienced a change in command. Major-General Edwin Vose Sumner "received a leave of absence"10 and Major-General Darius N. Couch took his place. Although the reason for the leave is not specified, Sumner probably suffered from nervous exhaustion since the near destruction of Sedgwick’s division was precipitated by his "rash advance"11 between the East Woods and West Woods at Sharpsburg. According to the Second Corps historian the old general “was heartbroken at the terrible fate of the splendid division on which he had so much relied, which he deemed invincible, and his proximity to the disaster had been so close as to convey a shock from which he had not recovered.12 Nevertheless the ‘Old Bull of the Woods’ would re-join the Army of the Potomac on Nov.6 at Rectortown to assume command of one of the ‘grand divisions’ “consisting of two corps each” when Burnside later reorganized the army. In the final days of October, 1862, the Army of the Potomac, led by the Second Corps, marched from Harper’s Ferry and crossed to the east bank of the Shenandoah River. Slocum’s Twelfth Corps was left at the ruined arsenal "to guard the line of the Upper Potomac" while the remainder of the army moved in a southwest direction following the line of the Blue Ridge Mountains. McClellan’s intention was to split Lee’s army and "beat them in detail or else force them to concentrate as far back as Gordonsville". The latter scenario would allow McClellan to advance on Richmond via Fredericksburg.13 However, neither would be the case since, on Nov.7 as the army camped at Warrenton, the second major change occurred. McClellan was removed from command of the army and Ambrose Burnside named to replace him.

McClellan’s removal caused uproar in the ranks of the army. Loyal McClellanite officers threatened to resign or rebel or both. Others felt that McClellan should turn the army around and overthrow Washington. The outrage of his ‘boys’ must have been quite gratifying to McClellan’s not inconsiderable ego, but the Colonel of the 108th New York took a more dispassionate view about the change. Oliver Palmer questioned the timing and public perception of the decision, not the validity of the move. He felt that McClellan’s dismissal “will be construed into an act of political spite and may produce a sad state of affairs” but the “best interests of the government may have required what has been done” since his “unfitness for the position must have been as well known to the Government before the Army was set in motion from Harper’s Ferry as now.” For Palmer the paramount question was, if the government knew of McClellan’s inability “and if a change was contemplated” then “why in God’s name was it not made” earlier? Quite perceptively, Palmer went on to pin-point the nature of the bond between Little Mac and his men. He realized that McClellan’s “caution is really the element of his popularity, not his military knowledge or great generalship.” For McClellan, the war, was a “great game” of pomp and circumstance and of “secret movements” where the “movements are exceedingly cautious”. His men knew that he would never take a risk or commit the army completely and hence “McClellan’s caution pleases them.” Omar Richardson of Company C in the 108th reflected his colonel’s viewpoint, although with less grammatical precision, in a letter to his family after the dismissal of the general. The 34 year old farmer from Honeoye Falls reported that the removal of McClellan “made some folk talk for a few days and was over.” Personally, he felt that the action was “the best thing that has ever hapened (sic)for the Government since it wass (sic) comensed (sic)” and the “greater part of the troops are well satisfied with the change.” Another member of Company C hated “to bid Gen. McClelland (sic) farewell” but rebounded from his disappointment with the belief that Burnside would lead them “to sure victory”, a belief least of all shared by Ambrose Burnside, McClellan’s successor. Perhaps in deference to his dear friend, Little Mac, ‘Burn’ did little to restore the shaken morale when he publicly avowed his reluctance and unsuitability to command the army. With restrained understatement, Palmer noted that Burnside’s confession did not "inspire confidence in his ability." Even with his departure, McClellan’s malaise would infect the Army of the Potomac until almost the end of the war.14 The Second Corps which, with the Ninth Corps, now formed the right wing of the army, the Grand Right Division, commanded by Major-General Sumner, departed Warrenton on the morning of November 15 and "took the road to Falmouth", located on the northern shore of the Rappahannock, opposite the city of Fredericksburg.15 Burnside had decided to follow his former chief’s plan to advance via Fredericksburg where he would cross the Rappahannock and with "a rapid move" descend on Richmond thereby ending the war.16 Similar to McClellan and many other Union notables, he believed that the capture of the Confederate Capitol not the destruction of its army would win the war. If Burnside’s plan was meant to catch Lee off guard, then the opening move worked up to a point. While the troops of Sumner’s Grand Right Division were entering Falmouth, in the early afternoon of Nov. 17,1862, Lee was still unsure of Burnside’s intention. The southern commander pondered Burnside’s options:

His troops and trains, as far as can be discovered, are moving toward the Orange and Alexandria Railroad; but whether with a view of massing them on that line of communication, to threaten Gordonsville, or fall down upon Fredericksburg, or to retire toward Alexandria, to be transferred by water south of the James River, I cannot discover. The railroad trains are kept in active operation; but it not known whether they are employed in carrying troops to Alexandria or in bringing them in this direction.

At the time of Sumner’s arrival, Lee’s line of defense at Fredericksburg was not only thin, it was almost transparent. To confront the 30,000 of the Grand Right Division, Lee had the "Fifteenth Virginia Cavalry, four companies of Mississippi infantry and Lewis’ battery of field artillery"17, a total of perhaps 400 men. Sergeant Ben Hirst of the 14th Connecticut recalled that he "had a talk with a native Butternut. He told me there were not over 300 rebels over the river at Fredericksburg".18 Sumner had suggested “crossing a portion of his force over the fords” near Falmouth “with a view to taking Fredericksburg” but Burnside thought “the condition of the ford” to be unsuitable and he did not wish to cross a force since it could become separated or isolated if the level of the river rose. Rain over the next few days may have justified Burnside’s caution yet Sumner’s massive division could have easily rousted the thin Confederate force and taken the city.19 Evidently the Rebel force was daunting enough, so Burnside chose to sit down and await the arrival of the pontoon bridges from Washington, completed 10 days later on Nov.27.20 Once again, the ingrained timidity of the Army of the Potomac restored the initiative to Lee, an occurrence that usually proved fatal.

The Second Brigade of French’s Division did not get time to rest at Falmouth. On Nov.18, the brigade that included the 108th New York, the 130th Pennsylvania and the 14th Connecticut, was detailed for guard duty at Belle Plain on the western shore of the Potomac River, about 12 miles northeast of Falmouth. Soon the men realized that the journey to Belle Plain would be much more difficult than they could have imagined. Around 4.p.m. on the evening of Nov.18, they left camp, two miles north of Falmouth, and the brigade leader, Colonel Dwight Morris of the 14th Connecticut, "was instructed to march us about 5 miles that evening thus making a nice easy march for us next day."21 Colonel Palmer, who did not have ‘the greatest possible confidence in the shrewdness of the Brigade Commander", suggested that, since Morris "was wholly unacquainted with the route, it would be very important in a night march to have a guide." Morris, however, sloughed off the suggestion since he felt quite confident in his own ability.22 Shortly after it started, the brigade promptly got lost. Over the next day and a half, the "bewildered" full bearded Morris marched the men "round and round, through woods, across streams and through farmer’s dooryards". At one point, the men "crossed the same stream four times and every now and then would about face and take the back track, and were some five hours in marching a distance of four miles."23 Almost 24 hours from the time that they departed Falmouth, the regiments finally floundered into Belle Plain and quickly realized that the euphonious appellation was a distinct misnomer. The morning light of November 20 disclosed "the fact that Belle Plain" was "a myth" "The name at least signified pleasant things" but the reality was

a plain, almost a marsh, 200 or 300 acres of low land which evidently at [a] very remote period has been submerged. There is not a single building of any kind in the plain. The only visible evidence of its having been inhabited is a standing chimney stack marking the spot once occupied as a fisherman’s grog shop.

At about midnight, while encamped on this "plain of desolation" the rains started and the camp was transformed into a large pond with "two thousand or more men" paddling "about like so many big ducks."24After the flood, the men quickly learned that their stay at Belle Plain would involve more than simple guard duty. Some of the troops were "detailed to do duty as stevedores and longshoremen", while others built roads. Major Pierce recalled:

All day I was working on the road. I had under my charge part of Co’s A and F, in all about 60 men and two mule teams, and we turnpiked and corduroyed about 5 rods of road. All of the road is bad enough but some portions of it even with the slight rains we have had are perfectly impassable, the mud holes taking mules in completely out of sight.25

A combination of labor, fatigue, living conditions and inclement weather led to the inevitable increase in disease and ailments which induced the men of the 108th to name their encampment "Camp ‘Valley Forge’.” On December 7, 1862, the New Yorkers left ‘Valley Forge’ to return to the world of the soldier when they re-joined the division at Falmouth. For the boys of the 108th New York, their stay at Belle Plain, "the cheerless God-forsaken hole", would seem only a dream when compared to the real nightmare about to be played out on the frozen plains of Fredericksburg.26

At 2 o’clock on the morning of Dec. 10, the men of the 108th New York were ordered to be ready for battle by 6.00 a.m. The usual cold quiet of the camp gave way to the activity of dreadful preparation. In the icy December darkness, the men shook off the comfort of winter sleep and, with the poise of seasoned veterans, moved surely to their tasks. They huddled around the campfires to cook rations and to share the latest scuttlebutt about the plans of Ambrose Burnside. They stomped the frozen ground to revive the circulation in their feet while they awaited their allotment of ammunition. Others rolled their blankets or carefully arranged the contents of the knapsacks which they had been ordered to leave in camp. Two men from each company would guard their belongings and their shelter tents.27 From the darkness visible the gray landscape began to emerge, punctuated by campfires encircled by the shadowy figures of men clutching boiling cups of coffee to stave off the cold, their murmuring voices audible and wispy in the frosty pre-dawn air. Around 4:30 a.m., as the 108th New York and the rest of the Second Brigade finished breakfast, Henry Hunt’s Federal guns on Stafford Heights opened a bombardment on Fredericksburg "for the purpose of dislodging the sharp- shooters who under cover of the houses were delaying the bridge-making".28 Half an hour later, the 108th left camp near Falmouth and "marched about 5 miles in a round about course for Fredericksburgh [sic]." The New Yorkers "proceeded to a point on the railroad opposite the city of Fredericksburg" where they "halted until almost night waiting for the completion of the pontoon bridges."29As the brigade waited at the railroad crossing near the Lacy House, the Federal cannonade continued but had little effect since the bridge building was still impeded by Barksdale’s Rebel riflemen across the river. Almost 8 hours later, Henry Hunt conceded the failure of his artillery to dislodge the Mississippi sharpshooters and devised a plan for an amphibious assault that would use “the pontoon boats of the first bridge, of which there were ten lying on the bank of the river, waiting to be added to the half finished bridge, cross over in them, and landing, drive out the rebels."30 At approximately 3:30 p.m. in the fading daylight, the Second Brigade witnessed the heroic water borne assault of the 7th Michigan, supported by the 19th and 20th Massachusetts, against Barksdale’s men on the opposite shore of the river. When the assault force landed on the opposite shore, a war correspondent described the action:

The rebels pop up by the hundred, like so many rats, from every cellar, rifle pit, and stone wall, and scamper off up the streets of the town. With all their fleetness, however, many of them were much too slow. With incredible rapidity the Michigan and Massachusetts boys sweep up the hill, making a rush for the lurking places occupied, and gaining them, each man capturing his two or three prisoners. The pontoon boats on their return trip took over more than a hundred of these fellows.31

Just as darkness began to settle, the bridge was completed "and Sedgewick’s (sic) [Howard’s] division crossed the river and after sharp street fighting drove the rebels from the city."32 Shortly afterward, French’s Division was ordered across the river "but just before reaching the bridge, the order was countermanded and we bivouacked for the night on the Falmouth side of the river” where the officers and men of the 108th spent a miserable night encamped by the Lacy House.33 Major Pierce recalled how he and his two bed-mates, lieutenants Sam Porter and William Merrell, attempted to share one blanket. All three huddled together on the frozen ground behind the mansion with Porter in “the middle all night” and Pierce and Merrell as bookends. Sometimes “Merrell had blanket enough to cover him, sometimes I did but about 2 A.M. of Friday I dug out, built a fire and toasted until it was time for my detail.34 On Friday, December 12, just after sunrise, almost twenty five days after its arrival in Falmouth, French’s Third Division finally crossed the Rappahannock on the pontoon bridge placed near the Lacy House and entered the battered town on the opposite shore.

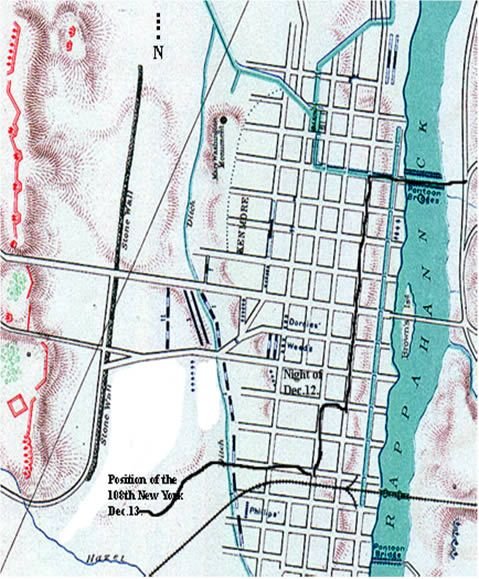

At the time of the battle the main streets of Fredericksburg ran roughly north to south and formed almost a rectangular grid in relation to the river. The four main streets which ran parallel to the river and formed the longer side of the rectangle were: Sophia or River Street, the most eastern and closest to the river; followed in order by Caroline, Princess Anne and finally Prince Edward Street which, in 1862, marked the western edge of the town. Numerous east-west streets vertically intersected these four parallels and thus, when the Third Division crossed the river, the Second Brigade, now under the command of Colonel Palmer35, debouched on the shore near the foot of Hawke Street that vertically intersected Sophia Street at the river’s western edge. After waiting on Sophia St. for some time, the brigade moved west on Hawke St., turned left on Caroline, the next parallel street, and filed south to spend the evening in the town. On the night of Dec. 12, French’s Division spread out along Caroline Street from the intersection of Charlotte St. on the south to Hawke Street on the north, with Kimball’s Brigade on the left, Marshall in the centre and Palmer’s Brigade as the division right.36 The Third Division lay "between the First and Second Divisions, in the town" with the former deployed mainly along Princess Anne Street and the latter on Sophia Street.37 The Second Corps had been in position since early in the day but once again Burnside hesitated and was unsure.

The 108th New York at Fredericksburg, Dec.12-13, 1862.

(O.R. Atlas, Plate 32, no.2)

The failure of the pontoon bridge-trains to arrive when expected and Burnside’s reluctance to force the issue, gave Lee the time to fortify the heights to the west of Fredericksburg. Jackson’s Corps defended the southern part of Lee’s line on Prospect Hill from Deep Run to Hamilton’s Crossing which was approximately 5 miles south of Fredericksburg. From Deep Run, north to Marye’s Heights, directly behind the town, Longstreet’s Corps prepared the northern end of Lee’s defensive line.38 Since General Lee made it quite clear that Burnside’s rapid descent on Richmond was no longer feasible, the northern commander had to abandon his original intent and devise a new plan of battle. Burnside decided that the main strike force would be the Left Grand Division under Franklin who would attack Jackson, south of the city. Sumner’s Grand Right Division would hold Longstreet in place and take advantage of any attempt Lee might make to reinforce Jackson by weakening Longstreet. The Centre Grand Division, under Hooker, would be held in reserve and reinforce where needed. That Burnside intended Franklin to be the main assault is verified by an order sent to General Hancock, late in the afternoon of Dec.12. Hancock reported:

At a later hour orders were received to march by the leftflank across Hazel Run, thence down the Rappahannock, forming in the rear of General Franklin’s grand division, my division taking the lead.,and each division of the corps marching in three parallel lines of brigades... Subsequently it was determined to defer this movement until the next morning.

That the Second Corps was ordered to form "in the rear" of Franklin strongly suggested that Burnside still viewed their role as supportive. However, by the next morning, the plan had altered. Once more,Hancock was informed "that General French’s division would attack the enemy in front of the town, and that my division would support him." Later in his report, Burnside wrote that

I supposed when I ordered General Sumner to attack that General Franklin’s attack on the left would have been made before General Sumner’s men would be engaged, and would have caused the enemy to weaken his forces in front of Sumner, and I therefore hoped to break through their lines at this point.39

During the course of the day Franklin’s orders or his interpretation of them led to a major foul-up and the Left Grand Division never did fulfill its role in the battle.40 As a result the main event switched from south of the town to the plain directly west of the town. Consequently at Fredericksburg, the 108th must have wondered if its lot in life was to assault heavily fortified sunken roads. The road at the base of Marye’s Heights was not only sunken but was, "on the side toward the town, bordered by a substantial stone wall, shoulder high."41 From the heights above the wall and down the slope to the wall itself, were rifle pits, artillery lunettes and a system of fortifications which Lee had at least three weeks to create and perfect while Burnside waited for his pontoons and lost whatever initiative he might have had. In other words this sunken road was not simply a replay of Antietam but French’s Third Division of Couch’s Second Corps in Sumner’s Grand Right Division once again would get the first crack at the rebel position.

As the troops waited and watched the heights across the plain become more formidable, the frustration and boredom led to violence and vandalism. The looting had started on the morning of the 12th, when the Rebel force withdrew from the town, and when the Federal soldiers, who had endured the street fighting of the previous day, realized that Fredericksburg was now a conquered city of the Confederacy.42 More and more troops arrived, waited and freely roamed the town. Even though the shell fire from the Rebel artillery provided an element of danger, the pillage of the town continued unchecked and reached epic proportions by the next morning. On Caroline Street, Lt. Sam Porter, Major Pierce and Lt. Col. Charles Powers sat at the base of a small peach tree, chatting idly and taking note of the frenzied activity around them. Pierce recorded that some of the boys “came into our place loaded with silver pitchers, silver spoons, silver lamps and castors." Furthermore, he continued, splendid "alabaster vases and pieces of statuary were thrown at 6 and 700 dollar mirrors." The soldiers "seemed to delight in destroying everything. Libraries worth thousands of dollars were overhauled and thrown on the floor and in the streets." Major Pierce, despite his professed repugnance, profited from the looting and sent home a “cup” in care of the Porter family and Sam Porter, whose social conscience and sense of propriety evidently did not extend to the enemy populace, also sent his “few trophies” to his father.43 An enterprising member of the 108th New York “found a pile of papers in a garret” and began to sell the used items in the street. “‘Baltimore Clipper, ten cents a piece’ rang out clear and strong” as officers and men gathered around the would-be newsboy “eager to purchase.” The fraud was soon discovered but the ‘newsboy’ had made his profit44. As the day wore on into evening, the “streets were resonant with a chorus of voices” when “the city became vocal with music.” “There were many pianos left behind, most of which had been knocked out of tune, but they served very well for a rough kind of ‘Yankee Doodle’ or ‘Star Spangled Banner’”. Toward morning a Mardi-Gras-like parade proceeded along Caroline Street:

Clothed in the costumes of Virginia that were in fashion in the days of Mary Washington, a procession marched along the line with all the fun and frolic of Harlequin in his happiest mood. An old family coach, a relic of colonial days, with its yellow body resting on untrusty thorough braces, its artistic ornamentation and gilding long since obscured and covered with dust, was hitched to a mule with ears so long that they dropped on either side of his head by mere force of their weight, and driven the length of Caroline Street by a soldier in the mask of a negro, with two representative belles of a by-gone age sitting on the back seat and scattering smiles and kisses to an applauding crowd.45

Although General Thomas Meagher of the Irish Brigade piously asserted that his Irishmen "abstained from any act of depredation", at least "one gigantic private of the Irish Brigade"was observed on two occasions "wearing the white-satin bonnet of some fair ‘Secesh’ bride".46 The frivolity continued but, like the damp misty fog, began to dissipate towards mid-morning. They left the pianos in the street, along with the broken china, the gutted feather beds, the torn books– fragments of a civilized time before the war- and re-formed into regiments for the desperate assault on Marye’s Heights.

At 9:00 a.m. on the morning of Saturday, December 13, the 108th New York, under the command of Lt. Colonel Powers, and the other regiments of French’s Division moved forward. The division moved to Princess Anne Street, directly west and parallel to Caroline, and waited about an hour while Rebel artillery shelled the area. Since members of the brigade noted that the regiments "halted between the church and court house" during the delay, therefore Palmer’s Brigade was located on Princess Anne Street between Hanover Street and George Street47. The Rebel guns found the range "and their shells were dropped among us with a precision that was decidedly uncomfortable". While four members of Co. ‘F’ sat on the curbstone, near the Presbyterian Church, a Rebel shell passed through a house and "struck the curb stone on the east side of the street. It exploded and made awful work." Dr. Whitbeck, the surgeon of the 108th , who had been nervously attempting to remain calm while under artillery fire for the first time, quickly dismounted in order to attend the wounded men. Nearby other members of company F were shaken by the explosion. Russell Disbrow, a twenty two year-old farm worker from Seneca County, New York, waited nervously but as the debris from the shell suffused the scene, he began to cough violently.48 Palmer understood that it "was exceedingly trying to the courage of the men to be kept idle under such circumstances; but I was waiting for the movement of the column in advance and was compelled to stand and take it."49 The men stood and were inspired by the example of Lt. Frederick Fuller, Acting Signal Officer of the 52nd Pennsylvania, who kept to his post in the seventy-foot tall belfry tower of the court house, despite the Rebel artillery. Obviously the tower “was a conspicuous mark for the Confederate gunners, one of the upright posts that held the belfry having been knocked out already, yet, to the men in the street below, it was gratifying to see the faithfulness with which this officer did his duty in such a perilous situation."50

Shortly after 11:00 A.M., French’s Division was ordered into action. The First Brigade, under Brig. Gen. Nathan Kimball, took the lead and marched south on Princess Anne towards the railroad. As the main body of Kimball’s Brigade approached the depot, it turned right [west] and moved along one or more of the side streets, out towards the plain.51 One hundred and fifty yards behind the First Brigade, the Third Brigade, commanded by Lt. Col. John W. Marshall, followed at a similar interval by Palmer’s Second Brigade, retraced Kimball’s route. As the division moved closer to the railroad depot and away from the protective shelter of the more developed part of the town, all the brigade commanders noted "a most murderous fire from the enemy’s artillery." Palmer reported that after "leaving the city, and upon filing to the right, to pass through the depot, the fire of the enemy was severe."52 However, once on the open plain, in front of the sunken road, the men quickly faced another major obstacle. At “the western edge of the town the ground fell slightly and gradually” downwards to “a canal, about fifteen feet wide and four to six feet deep which ran clear around Fredericksburg. According to Francis Walker, the Second Corps’ historian, who was not a great supporter of the commanding general, Burnside had flatly denied the existence of the canal since he had claimed to have "personal acquaintance with the topography of Fredericksburg." The ditch or canal was "so deep as to be almost impassable except at the street bridges and, one of the latter being partly torn up, the troops had to cross single file on the stringers."53 Since none of the regimental reports for Palmer’s Brigade mentioned the canal as a problem, then it can be assumed that the 108th New York and its brigade mates crossed on the undamaged bridge. As he crossed the sluice or ditch, Morris Darrohn of Company C noticed that several men were “standing still looking at something” on the other side. When he moved closer, he saw the object of the crowd’s attention. With almost detached curiosity, the short stocky youth looked on at a “man lying there with both legs shot off below the knees” while the ripped and shredded flesh and fragments of bone still steamed in the frosty air. To the young veteran of the 108th after Antietam such sights now, though hideous, were not uncommon. “Pass on boys. Don’t stop to look at me,” said the dying man and Morris and the men moved on.54

Once across the canal, the ground rose, “forming a cover, behind which the troops were able to deploy.” Initially, the men were ordered to lie down and "remained in position about twenty minutes" after which they advanced at the double quick, on the enemy position.55 A Confederate gunner recalled the grandeur of the attack as “a magnificent sight”. They had “never witnessed such a battle array before: long lines following one another, of brigade front. It seemed like some huge blue serpent about to encompass and crush us in its folds, their musket-barrels gleaming brightly in the sunlight, their gay colors fluttering in the breeze.” As the advance continued, Kimball’s Brigade was shattered by the “dreadful work” of the Confederate artillery and "volley after volley" of infantry fire from the sunken road.56 Marshall’s Brigade suffered a similar fate and left the field littered with dead. Next in line was Palmer’s brigade as Burnside followed the tactics of his predecessor, one brigade at a time. When the Second Brigade advanced, the 108th New York formed the brigade left with the 14th Connecticut on the right and the 130th Pennsylvania in the centre. They “had to cross the plain about 80 rods in the face of a most destructive, accurate and deadly fire” and then had to confront “a high stone wall” with earth “piled up against the eastern face” with “insurmountable abatis that no infantry could overcome. “From this wall”, Palmer recalled, “were poured down upon us torrents of grape & canister and lead from the enemy rifles of the sharpshooters and we could fire only by guess.” In twenty minutes, one third of Palmer’s Brigade was "disabled". To the Chaplain of the 14th Connecticut, the brigade had been ordered into "a slaughter pen" and, as a man of God, he was obviously shaken by this glimpse of hell:

Who can depict the horrors of that scene? What language can adequately portray the awful carnage of that hour? The belching of two hundred pieces of artillery seemed to lift the earth from its foundation, shells screeched and burst in the air among the men as if possessed with demons and were seeking revenge, the shot from tens of thousands of musketry fell like rain drops in a summer shower, brother saw brother writhing in the agony of mortal wounds and could offer no succor, comrade saw comrade with whom he had marched shoulder to shoulder in the wearisome marches or shared the meager food on their cheerless bivouac, still in death.57

From the time that the 108th started to advance in line of battle “up to the base of the hill on the brow of which the reb cannons were placed it was a perfect shower of missiles warlike.” As Joe Ritt of Co. I charged the sunken road, his haversack, full of pancakes, came undone and lost its contents. Amidst the horror, Caspar Baker and Sergeant Frank Keyes watched in fascination as Joe created a pancake trail for others to follow. Disheartened as his pancakes got crushed into the mud, Joe wisely decided not to stop to pick them up. In the same charge, Major Pierce not only received a scalp wound which “tumbled” him but after he got up a “piece of shell took” him “on the inside of the left leg”.58 The leg was undamaged but it made him lame and he was furious that he could not catch up with his regiment which advanced only a bit further and then lay down in a protective depression in front of the sunken wall. The brigade had been shattered and scattered across the plain in front of the wall. Major Hincks and Fred Doten of the 14th Connecticut, who lost track of their regiment, “found Colonel Palmer of the 108th New York” sitting behind “a mound nearly up to the front” but even he “could not tell us where to find either regiment or brigade.” Palmer stayed at the front to watch with horror as “Brigade after Brigade was hurled into the vortex of death”. Brigades that followed, who could easily see the devastation in front of them and had to cope with moving over prostrate forms, some of which clutched at their pants as they tried to advance, finally accepted the futility of the attack and took cover. When the order to retreat was given at about sundown, Palmer made his way to the town to gather up the fragments of his brigade.59

As it did at Antietam, the order to retire caused difficulty for the 108th since Powers was in charge of the left wing and was separated from Pierce’s right wing by a fence which ran towards the Confederate position. At approximately 4:00 p.m., when the order to fallback was given, the left wing did not hear it and consequently remained on the field “till nearly dark.”60 When the retreat was called,, Claud Leonard and Sergeant Peter Anger, both of Company ‘F’, decided to take the shortest possible route to the pontoons and the "shelter of the Federal guns." They were forced to cross the canal at a point where the water was low and was little more than mud. Anger slid down the side of the canal and was lucky enough to land on a timber that had been thrown across. Leonard followed after him, but, about halfway across, a "deadly missile in the shape of a chunk of railroad iron struck square in front of the boys throwing up mud and water as if a torpedo has exploded" and tossed Leonard into the mire, where he wallowed helplessly. The sergeant, who was also in the mud, was unable to assist the hapless Claud. As the two soldiers struggled, a large black Newfoundland dog tried to make his escape across the same timber, “running as if the devil himself was after him”. The dog arrived upon the men just as they were extricating themselves from the slime and hit them with such force that all three of them ended up once more in the mud. However, all of the victims managed to survive since the sergeant latched on to the head of the dog while the private clung to the tail and the large Newfie swam to shore.61 Private Leonard, Sergeant Anger and the rest of the 108th New York got off comparatively lightly at Fredericksburg with a total loss of 92 men of which 4 were killed outright.62 Nevertheless, the continual senseless assault on Marye’s Heights was the second battle in four months for the 108th and disillusionment was setting in. Bitterly, Major Pierce concluded that crossing “the river in face of our enemy in superior force, strongly fortified, is an experiment that I don’t think Burnside will attempt again very soon.” Like “the whole army” he felt disillusioned, “disheartened and discouraged” and now realized for certain “that by arms the S[outhern]C[onfederacy] can never be subdued.63

When Palmer got back to town, he could only assemble 400 of the 1200 men that he commanded in the morning. Over the next two days, he managed to return his brigade to half-strength but still remained apprehensive about a future attack. However at 8 o’clock on the evening of the 15th , he was ordered to move across the river and return "to the old camp above Falmouth" which they reached "about two o’clock on the morning of the 16th, weary & worn yet thankful and happy." The Battle of Fredericksburg was finally over and the Federal army had been soundly defeated. Francis Palfrey of the 20th Massachusetts perhaps summarized best when he wrote that for the Army of the Potomac "one of its saddest and sharpest experiences was its brave, hopeless effort at Fredericksburg."64

Endnotes

1The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan, Selected Correspondence 1860-1865,edited by Stephen Sears (New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1989), pp.469,474 ; Stephen Sears, Landscape Turned Red (New York : Ticknor & Fields, 1983), p.296. Sears gives the following breakdown for casualties: Federal – 12,401, Confederate – 10,318 ; Palfrey,op.cit.pp.69,129.

2 Fourteenth Connecticut,pp .60-61 ; The Boys From Rockville,p.25 ;Darrohn-Letters, Oct. 3,1862 ;108th New York, pp.33,38;Omar Richardson, letter to his brother, Oct.23,1862, typescript of the original letters courtesy of Ms. Sara Gredler, Culpeper, Virginia, great-great-great-grandniece of Omar Richardson. Cited hereafter as Richardson-Letters.

3 Palmer-Diary, pp. 56-57; Pierce, p.156;

4Pierce, p. 156.Darrohn-Letters, Oct. 3,1862 ; Richardson-Letters, Sept. 29, 1862.

5108th New York, p.26, 108. The question of the color guard and Lt. Bloss at Antietam has caused some degree of confusion. The account cited on p. 26 claims that Lt. Bloss picked up the state flag from Casey and was wounded shortly after. Bloss (p.225) claims that the fallen standard bearer was Sgt. George Goff, who carried the regimental colors. Sgt. Woodhull (p.330) creates more confusion when he combines the fall of both flags and the wounding of Bloss. I chose the simpler story of Casey and Bloss since it matters little as to which flag was held up and Bloss was in the area when both men went down and he acted bravely under fire.

6 108th New York, pp. 190,443 The information from University of Toronto was obtained by a phone call to U.of T. Archives by the author.

7Information courtesy of B.A. Sullivan, Reference Archivist, Harvard University Archives. 108th New York, pp.190,443

8Blake McKelvey, "Rochester’s Part in the Civil War,", p.5.,6; 108th New York, pp.190

9108th New York, p.191, Phisterer, vol.4, p.3279.

10Francis A. Walker, History of the Second Corps in the Army of the Potomac(New York: Charles Scribner’sSons,1887), reprint Olde Soldiers Books (Gaithersburg,MD:Olde Soldiers Books Inc., n.d.), p.128. Hereafter cited as Second Corps.

11 Palfrey, p. 88.

12Second Corps, pp.117-18. See also Palfrey, p.122, re:Sumner’s demoralized state.

13 Second Corps pp. 131-132,136

14Palmer-Diary, pp.67-69,.71 ; Second Corps, 137; Richardson-Letters, Nov.23, 1862; Darrohn-Letters, Sept. 20,1862 ; Morris Darrohn, typescript of a section from unpublished memoir entitled “Recollections of Army Life”, currently being prepared for publication by Ron Erwin of Rochester, New York. Cited hereafter as Darrohn-Memoir.

15O.R. 21,1, p.101.

16O.R. 21,1, p.99; O.R. 19,2, p.552.

17O.R.,21,1, p.1016-17.

18Boys from Rockville, p.37.

19O.R. 21, p.47 ;O.R.,19,2, p.575; 108th New York, p.111; William Marvel, Burnside (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press,1991) p.167.

20O.R.,21,1, p.102.

21Boys from Rockville, p.41.

22Palmer-Diary, p.75.

2314th Connecticut, p.71.

24Palmer-Diary, pp.76-77.

2514th Connecticut, p. 71 ; Pierce, p.157.

26Palmer-Diary, p.86 ; 108th New York, p.35.

27Pierce, p.158.

28Robert Underwood and Clarence Buel, eds.,Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, 4 Vols.(Secaucus, N.J.:Book Sales Inc.,n.d.), Vol. 3, p.108 (hereafter cited as B&L followed by volume number and page) ; 14th Connecticut, p.78 ; Alfred Bellard, Gone For A Soldier, The Civil War Memoirs of Alfred Bellard ,ed. David Herbert Donald (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1975),p.180.

29Pierce,p,158 ; O.R. 21,1, p.300.

30O.R. 21,1, pp. 170, 183.

31John Robertson, comp., Michigan in the War, rev. ed.(Lansing, MI.:W.S.George &Co., 1882), p.273

32Pierce, p.159.

33Palmer-Diary, p.91.

34Pierce, p. 159.

35Charles D. Page wrote that Dwight Morris was ill and was left at Belle Plain (14th Connecticut, p.79). Brigade command therefore devolved onto Col. Palmer and command of the 108th went to Lt.Col.Powers.

36O.R.,21,1, pp.289-93,300-302 ; Pierce, p.160 ;14th Connecticut, p.81.

37O.R.,21,1, pp.233,238,246,247,249,252,253,258,271,285,286.

38The location of troops and movement is based on maps by Frank O’Reilly, John Dove and Steve Stanley, Battle of Fredericksburg, 5 maps (Fredericksburg: National Eastern, 2001) map 1.

The series is available from The National Park Service.

39O.R.21,1, pp.94,226.

40For a discussion of Franklin’s orders see Second Corps, pp.158-59 ; Francis Palfrey, pp.164-65 ;William Marvel, Burnside (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press,1991), pp.180-88.

41Second Corps, p.161.

42George A. Bruce, The Twentieth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry 1861-1865 (Cambridge: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1906) reprint Higginson Book Company (Salem:Higginson Book Company,1998), p.208.

43Porter-Letters, Dec.20,1862 to his father.

44 Darrohn- Memoir.

45Pierce, p.160 ; George A. Bruce, p.210.

46Second Corps, p.153 ; Boys from Rockville, p.75.

47Palmer-Diary, p.92 ; 14th Connecticut, p.81 ; Boys from Rockville, pp.73,76 ; Pierce, p.162.

48For the information and documents pertaining to Russell Disbrow, I am indebted to Ken E. Byrd of the University of Indiana, the great-great-great nephew of Russell S. Disbrow.

49Palmer-Diary, p.92 ; Pierce, p.162.For a more detailed and varied discussion of the incident with the shell see Robert Marcotte, “For the 108th New York men, the effects of a single shell epitomized Fredericksburg’s horror.”, America’s Civil War, November, 2002, pp.20-24.

5014th Connecticut, p.82 ; also Frederick L. Hitchcock’s account of Fuller in his War from the Inside, p. 115.

51O.R.,21,1, pp. 280,291,293. The side streets were in the area of the present day Lafayette Blvd.,Wolfe or Charlotte Streets.

52O.R.,21,1, pp.280,300,304 ; Boys from Rockville, p.75 ; 14th Connecticut, pp.83,89.

53Second Corps, p.162- 63; B&L, vol., p. 111; see also Palfrey, p.167.

54O.R.,21, pp.300,301,302 ; Darrohn Memoir.

55O.R.,21, pp.223,300.

56William Miller Owen, In Camp and Battle with the Washington Artillery of New Orleans (Boston: Ticknor and Company,1885), rpt., A Firebird Press Book(Gretna, LA.: Pelican Publishing Company,1998), p.186.

57Palmer-Diary, p.95 ; Francis Palfrey, p.161 ; 14th Connecticut, pp.85-86.

58Pierce, p..

59Pierce, p.161,162 ; Palmer-Diary, p.96 ; 108th New York, p.280; 14th Connecticut, pp.86-87.

60O.R.,21,p.300, 288.

61George H. Washburn, A Complete History of the 108th Regiment N.Y. Vols., from 1862 to 1887(Rochester: n.p.,1887), p.28. This is a 32 page pamphlet and appears to be an earlier version of the regimental history, published later in 1894. This work apparently was part of a program printed for the "Dedication of 108th Regiment Monument on the Battlefield at Gettysburg, PA., Tuesday, Sept . 4th,1888." A copy was provided by the generosity of the Rochester Historical Society. Hereafter cited as 108th New York Pamphlet.

62O.R.,21, p.131. Palmer, in his report, mistakenly calculates "192"(O.R.,21, p.301).

63Pierce, p.163. Pierce’s views would cause some problems with his brother officers. He was a confirmed disciple of George B. McClellan and saw Little Mac as the only possible hope for the Army of the Potomac.

64Francis Palfrey, p.190.